Summary

Furnishability is a concept of quality, where good furnishability give more and varying kinds of furnishings. Furnishability doesn’t only mean space for furniture, it also means space for mobility and the use of the dwelling itself. Good furnishability and flexibility often goes hand in hand, where more space for furniture also means space for other uses and the ability to adapt.

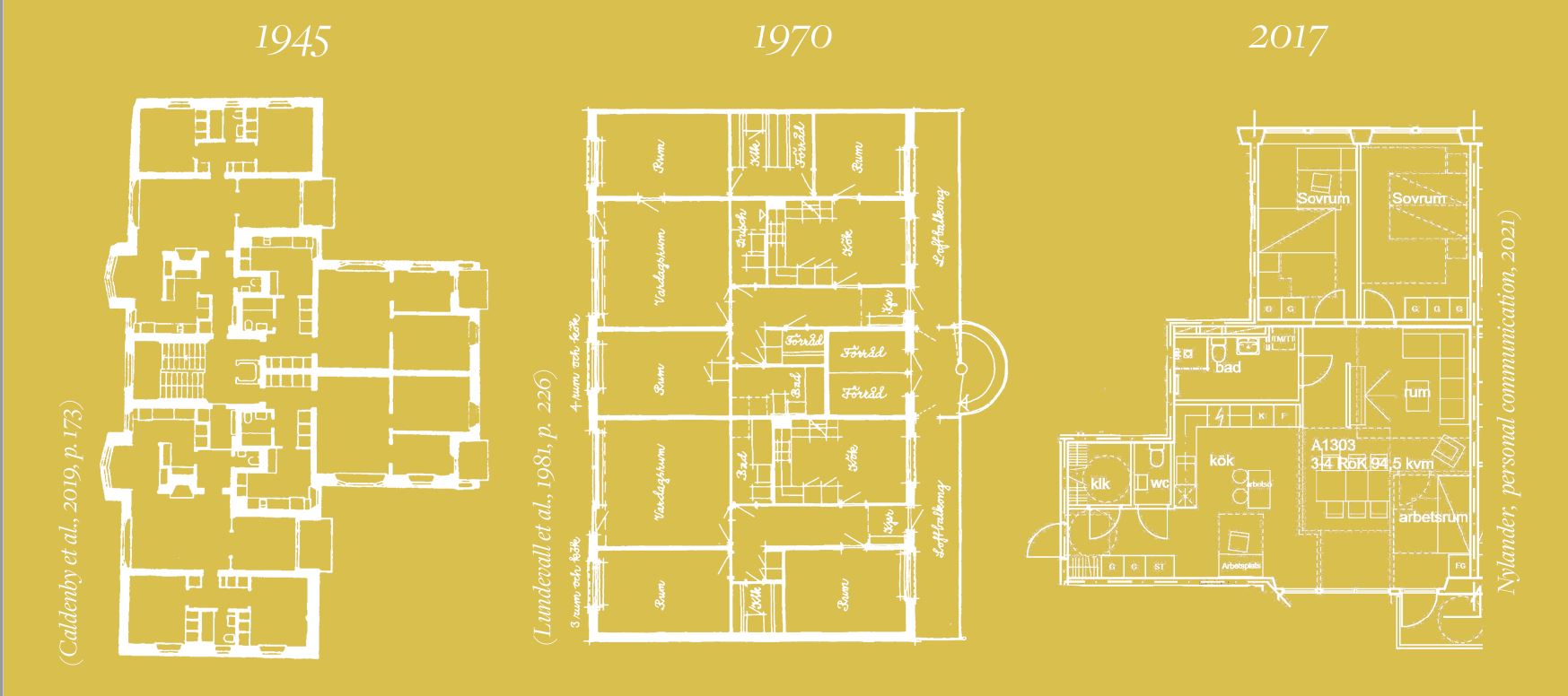

Research on the good dwelling, and in extension furnishability, started in the 1940’s, where the post-war period turned into a fresh start for Swedish housing politics. The state took the responsibility for housing construction, where furniture’s measurement of function and furnishability was a part of the new norms that were created. Housing qualities turned available for all, where the implementations counteracted against the current problem of overcrowding.

The Million programme took place in the 60’s and 70’s, where it was met with critique regarding facades and demolitions. The focus on the good plans were put in the dark. 60% of everything built during this period was 3 R&K or larger, where the standard in many cases were high and apartments were well designed for a more diverse use.

During the late 80’s and early 90’s, Swedish housing politics got a bit of a bump, where all state aids and subsidies regarding housing disappeared, alongside the housing department and housing committee. The research done in the 40’s was now forgotten. With the state’s shrinking role, construction companies started to take over and the new focus was profit. This resulted in the housing situation that’s currently going on today, with shrinking dwellings thanks to expensive properties, high building costs and people who can’t afford larger dwellings. Smaller apartments at 1 – 2,5 R&K are the most common types of apartments built today, where a lot of them are under 55 m². The open plan is instead used to make the dwelling look and feel bigger. The loss of the results of housing research is noticeable in contemporary housing, where the shrinking dwelling is proof.

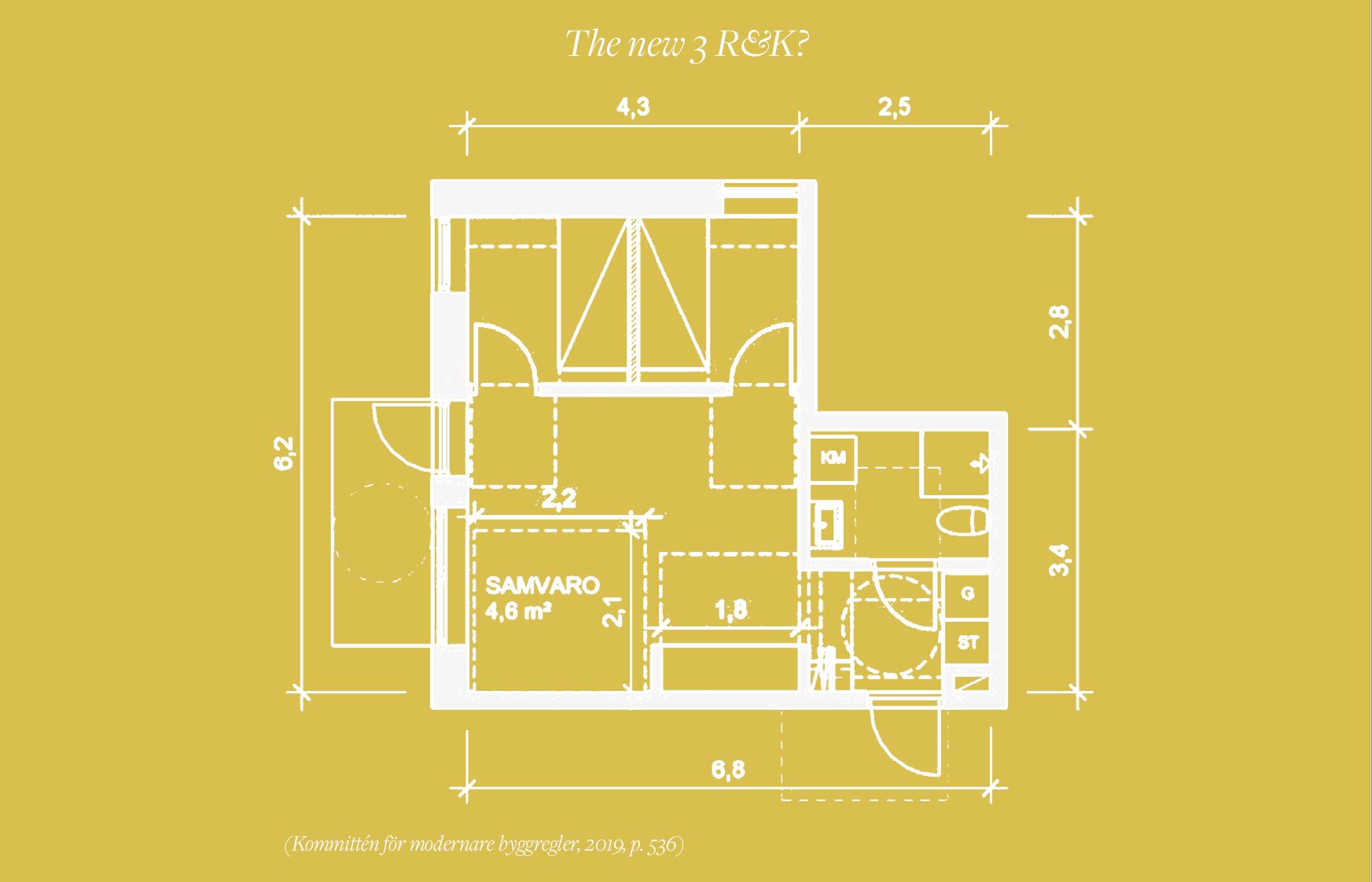

There’s discussions that have been brought up regarding the dwelling’s design and meaning. One of them is about KMB’s (The committee for modernized building regulations’) proposals on dwelling design. One of them is the reformation on Boverket’s building regulations (BBR) where they want to decrease the demands, e.g. being able to have bedrooms smaller than 5 m². Another one is being able to squeeze the sizes on dwellings for more than just students. They argue that one furniture can act like multiple, e.g. a bed being used for both sleep, socializing and dining. This results in fewer furniture, but also fewer ways to furnish.

KMB’s proposals have received backlash, stating that the proposals will in fact not increase but rather decrease the qualities and use of dwellings. The royal institute of british architects’ research on dwellings show that people can’t use their dwellings as intended and that a couple of extra square meters would give them the space they need.

Research shows that housing has shrunk by 10-15% during the last 20 years. Since 2014 , the number of smaller apartments has risen with over 10 percentage points, where the corresponding number has decreased for larger ones. This change and adaptation has happened very quickly, which is reflected through the proposals KMB has put forward.

In conclusion: Smaller dwellings give worse preconditions for use and variation, where too small dwellings limits the use and makes it hard to fit everything. It is common that people own more and larger furniture than what’s recommended by Swedish Standard. Too small dwellings therefore decrease the quality of life for its residents.

Flexibility is a basis for the use of dwellings and furnishability. It helps to adapt the dwelling for new needs and conditions, e.g. different social constellations, the needs of individuals and changes with age.

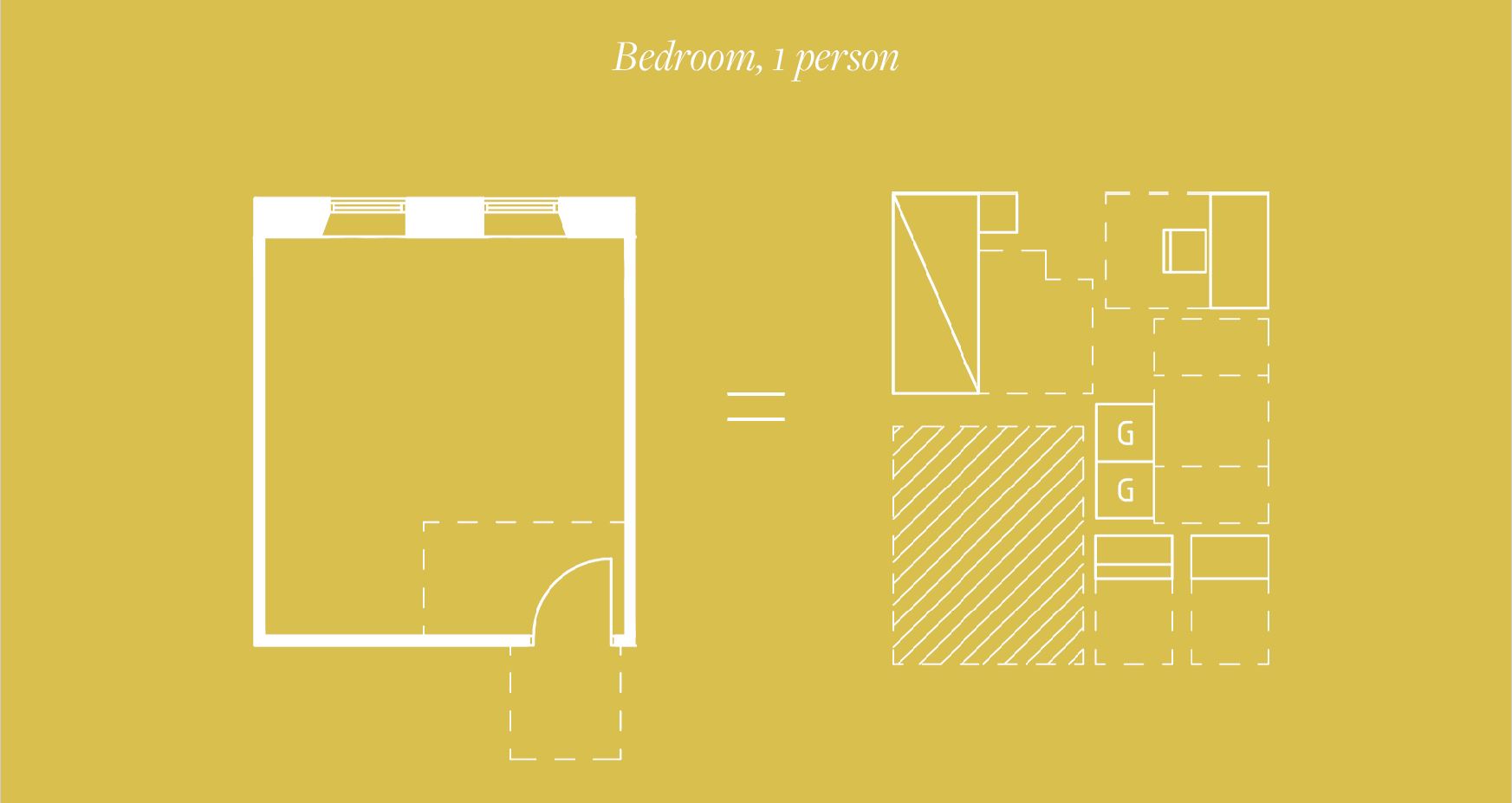

Rooms have different uses depending on what needs that have to be fulfilled, where rooms without set functions can be adapted. The different rooms should be able to fit furniture that are meant to be available through normal use in e.g. a bedroom or a living room. A bedroom for one person should be able to fit wardrobes, a bed, a bedside table, a desk with a chair, bookcase, space for personal belongings and free space on the floor.

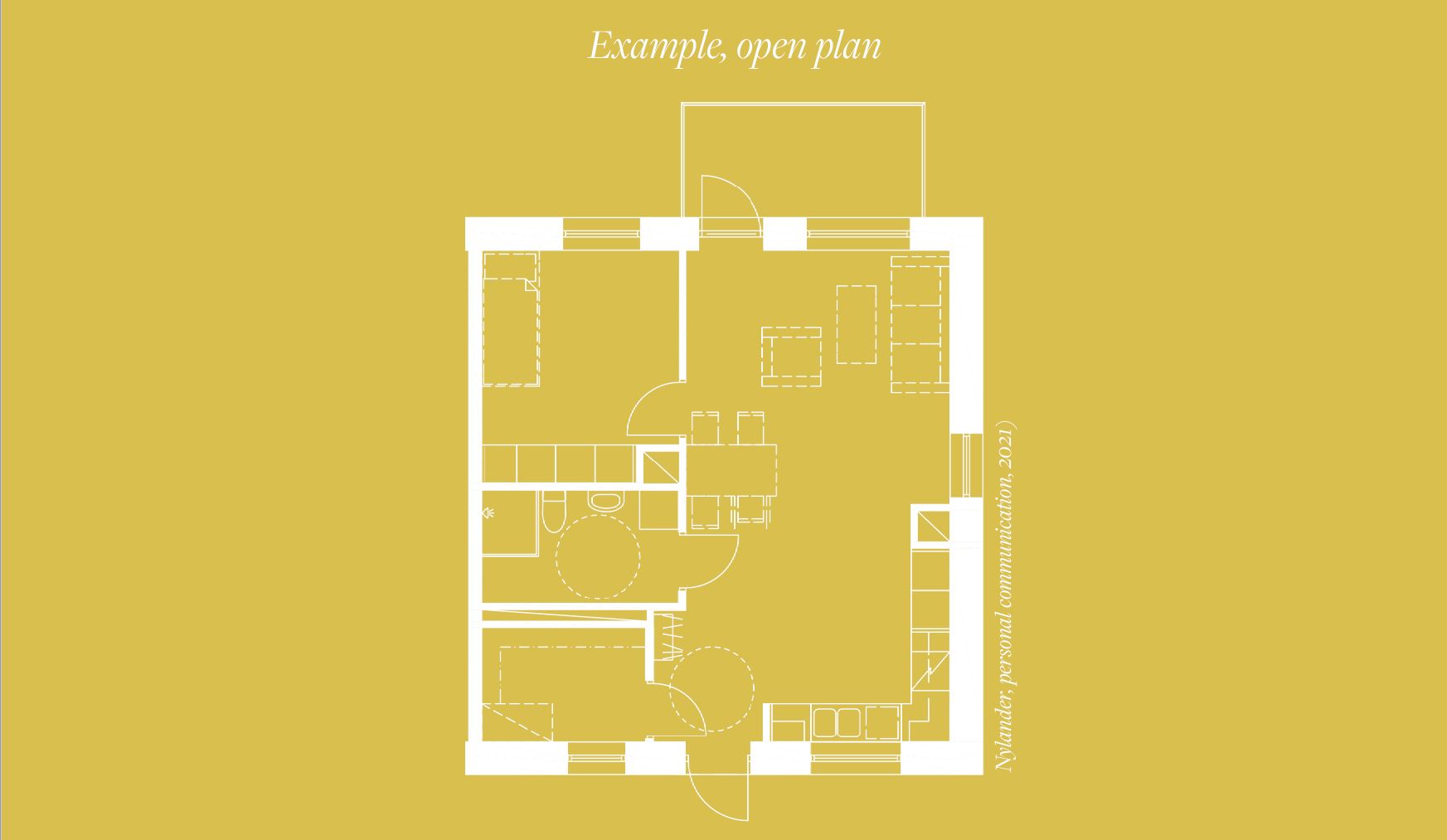

Something contemporary for the living room is its relation to the kitchen with the open plan. Since its introduction 20 years ago, the majority of new dwellings have implemented it. Here, the social connection is made between the rooms, where the removal of the wall makes the rooms more open and inviting. The more difficult aspect with this kind of solution is the absence of the wall, where furniture from the living room are dependent on it, e.g. bookcases and TV screens. Noise pollution is also a downside with the inability to close a door. A solution could be a glass wall with a door, to keep the visual aspect but be able to shut off when needed. A curtain can also help break the visual contact.

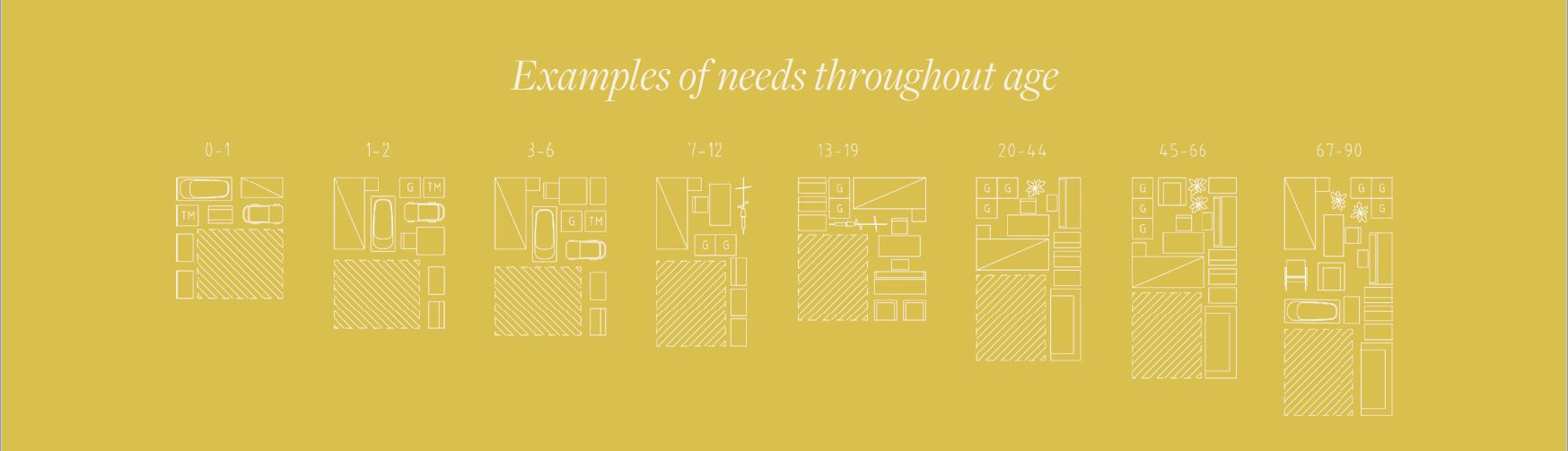

Besides the needs of the room, the needs of humans are shifting throughout life. There’s a big difference in the needs of a child and the needs of an older adult. In addition to the needs with age comes the individual’s lifestyle and wishes, where one type of design can fit one person well and another not at all. Variation is the key to make the dwelling suitable for more people.

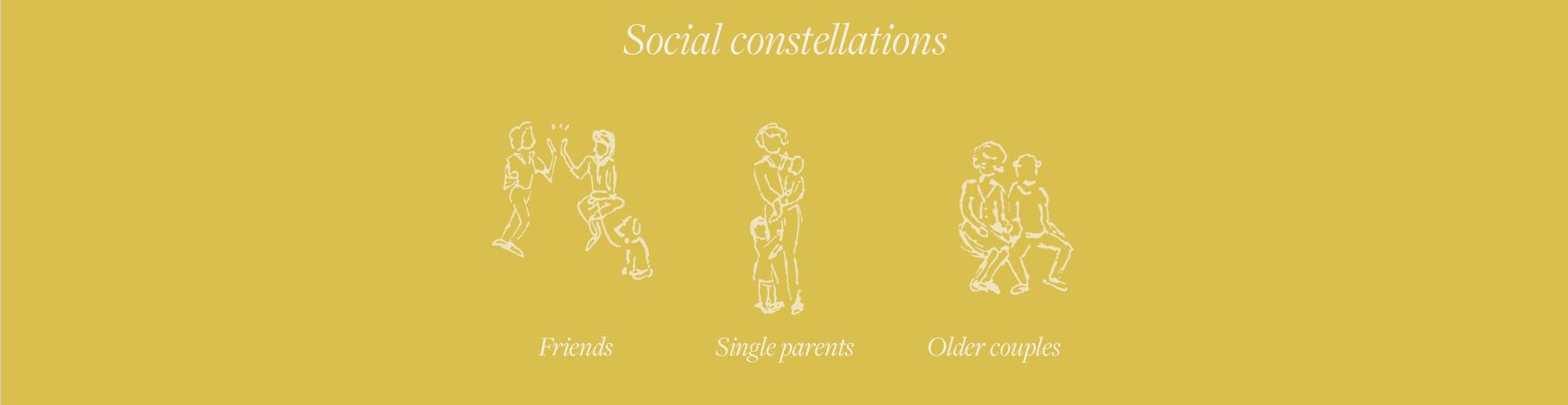

The dwelling cannot only fit the nuclear family or the young couple, but must also fit for other types of social constellations. Older couples, friends who live together, single parents and collectives are common groups of people in society where one kind of housing isn’t fit for them at all. To be able to fit more people better, the rooms should be general to be alternated in their use.

But what affects furnishability? What should be thought about? The three identified factors are:

placement of openings and installations,

space and movement, and

Room size and shape in relation to furniture

Together, these three lay the groundwork for good conditions regarding furnishability and flexibility in dwellings.

When it comes to placement of doors, it is important to think about what will happen around them. If the room has more than one opening, passageways should be included in the decision of placement. Windows are more flexible because you can furnish in front of them. The distance from the adjacent wall is important to not lock its use.

For installations such as switches and sockets, placement is very important to not prevent furnishability against walls with e.g. bookshelves. Shafts and electrical cabinets are often placed early in the design process, which makes it easier to implement them in regards to the rooms and furnishability.

Space and movement is the second aspect. There are four kinds of spaces to account for when designing. These are:

Space for furniture

user space around furniture

Passageways and

Space with no functions

The two most commonly seen are the space for furniture and their use, where passageways and functionless spaces are created and adapted after their placement.

The space most often forgotten is the functionless space, or the free space. The free space makes room for activities and spontaneous use, and to fulfill its function it needs to be at least 5 m². This space should be included in all rooms without a permanent function.

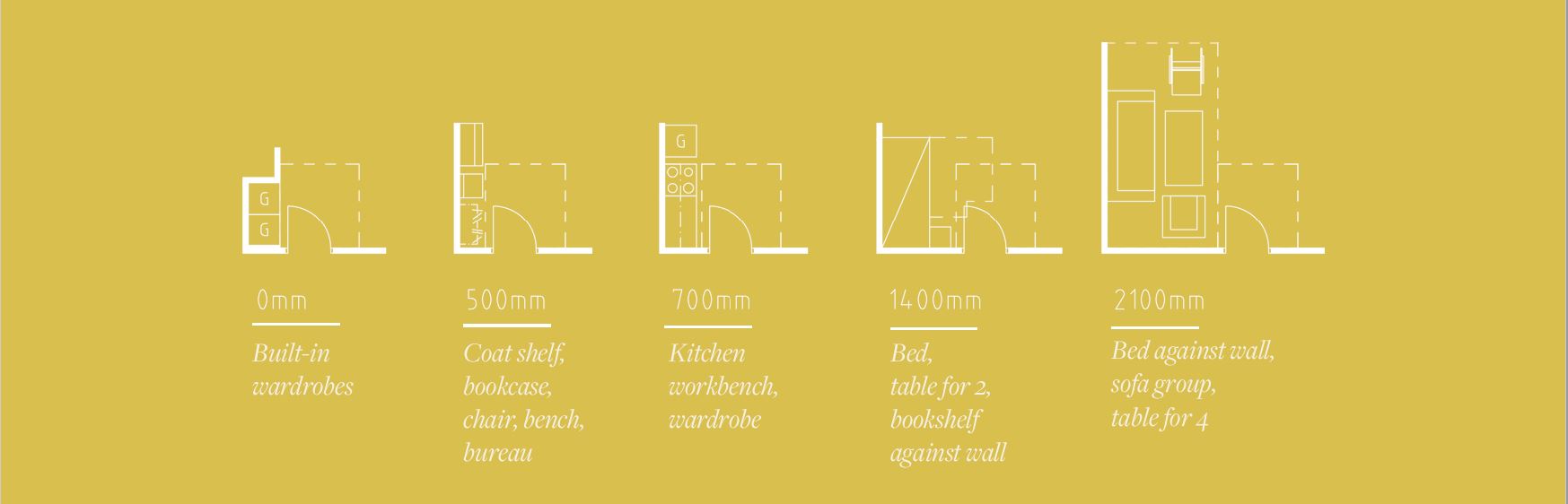

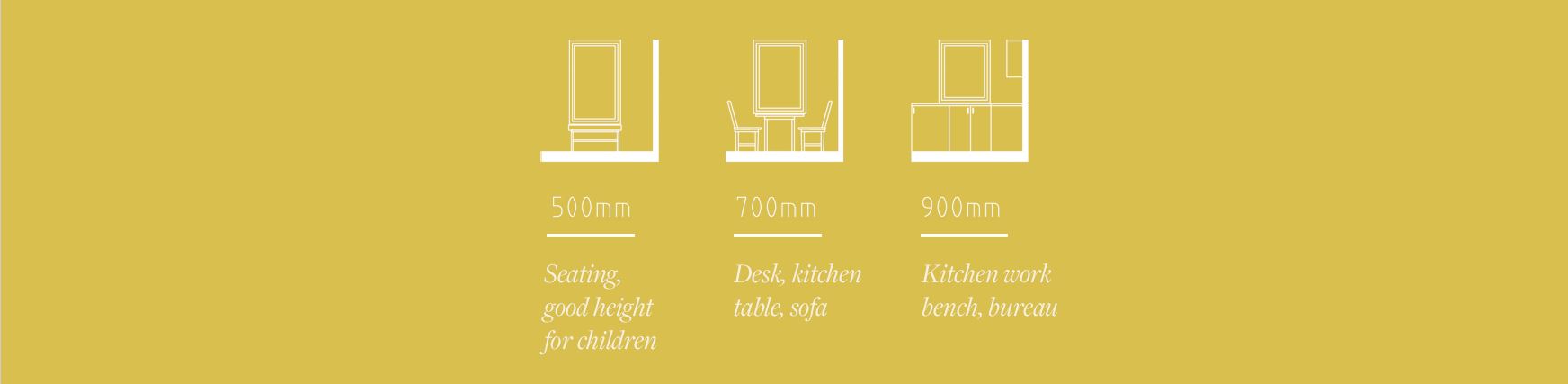

The last factor is the room size and shape in relation to furniture. The size of a room indirectly decides what furniture can fit and how it can be used. It must be big enough to contain both furniture, user space and passageways. Generally, oblong or narrow rooms should be avoided, where its shape makes it harder to alternate the direction of furniture. Open corners give more possibilities to furnish the room and are easy to furnish against.

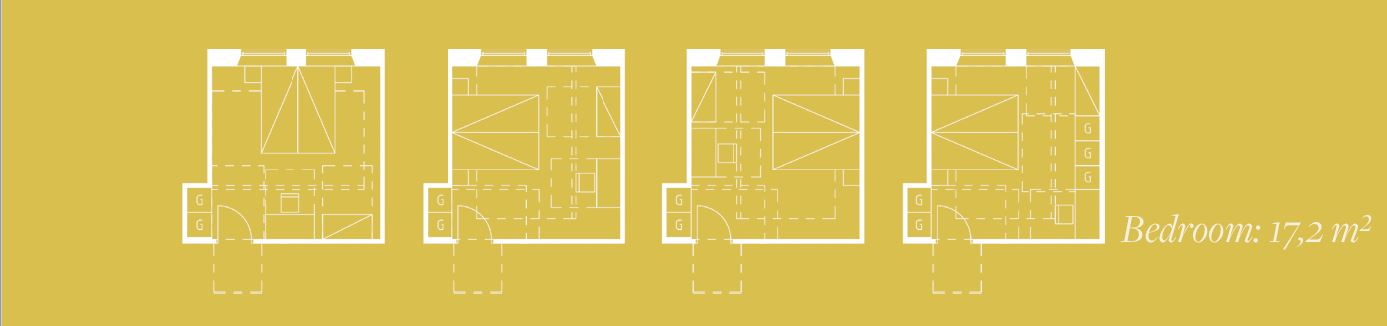

Some examples are shown here on how big rooms could be to house different kinds of furniture and furnishings, where all rooms can be furnished in at least two different ways. What these rooms have in common is that they’re approximately 2,5 times bigger than the combined area of all furniture. This provides enough space to furnish in different ways, have a minimum of 5 m² free space and room for passageways.

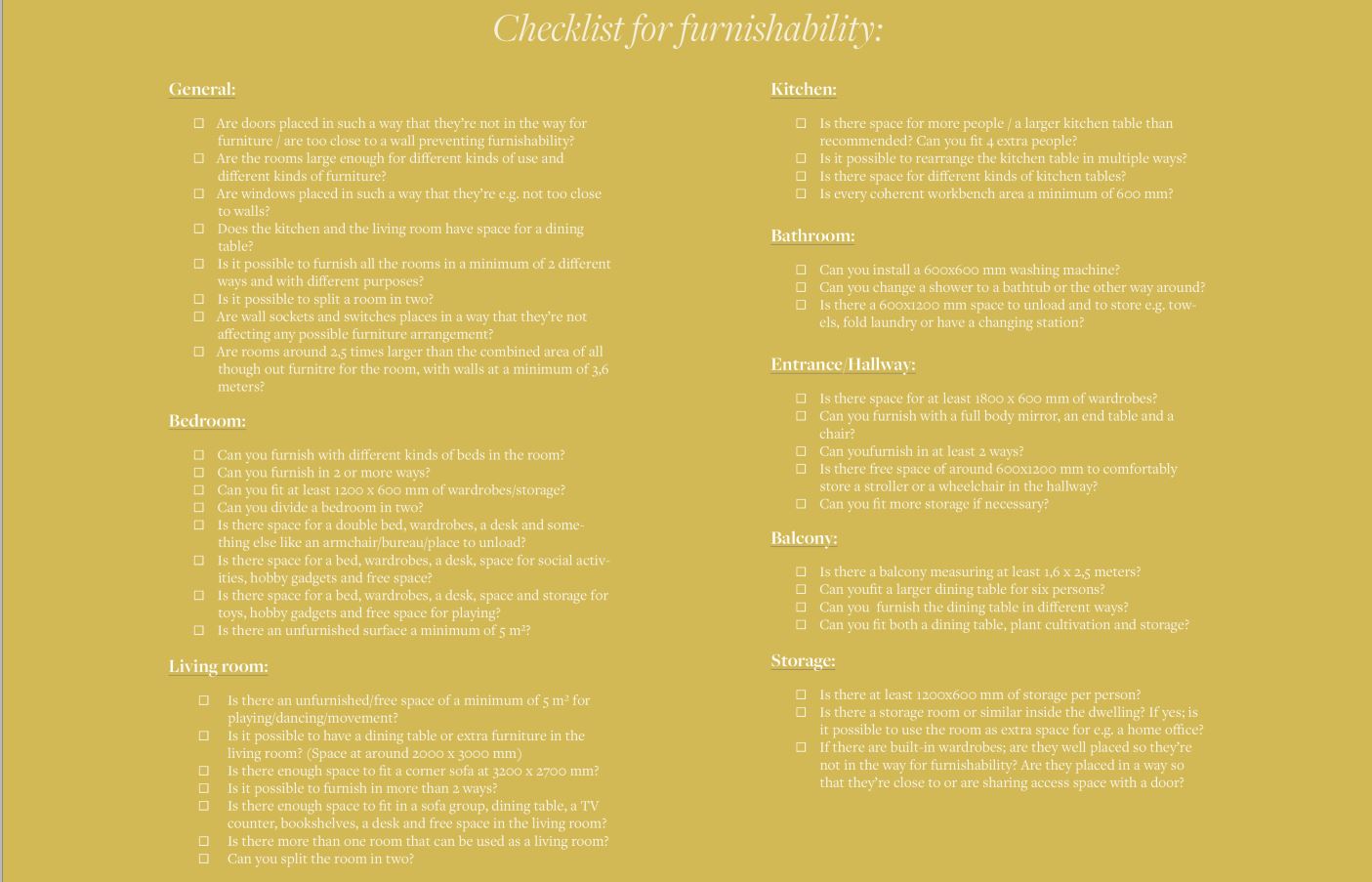

In conclusion; both the large and small scale are important when designing for furnishability. I’ve created a checklist: The more checkboxes you can tick in, the greater flexibility and furnishability is provided to the dwelling. This checklist can be used in the early days of designing to secure a larger generality from the start.

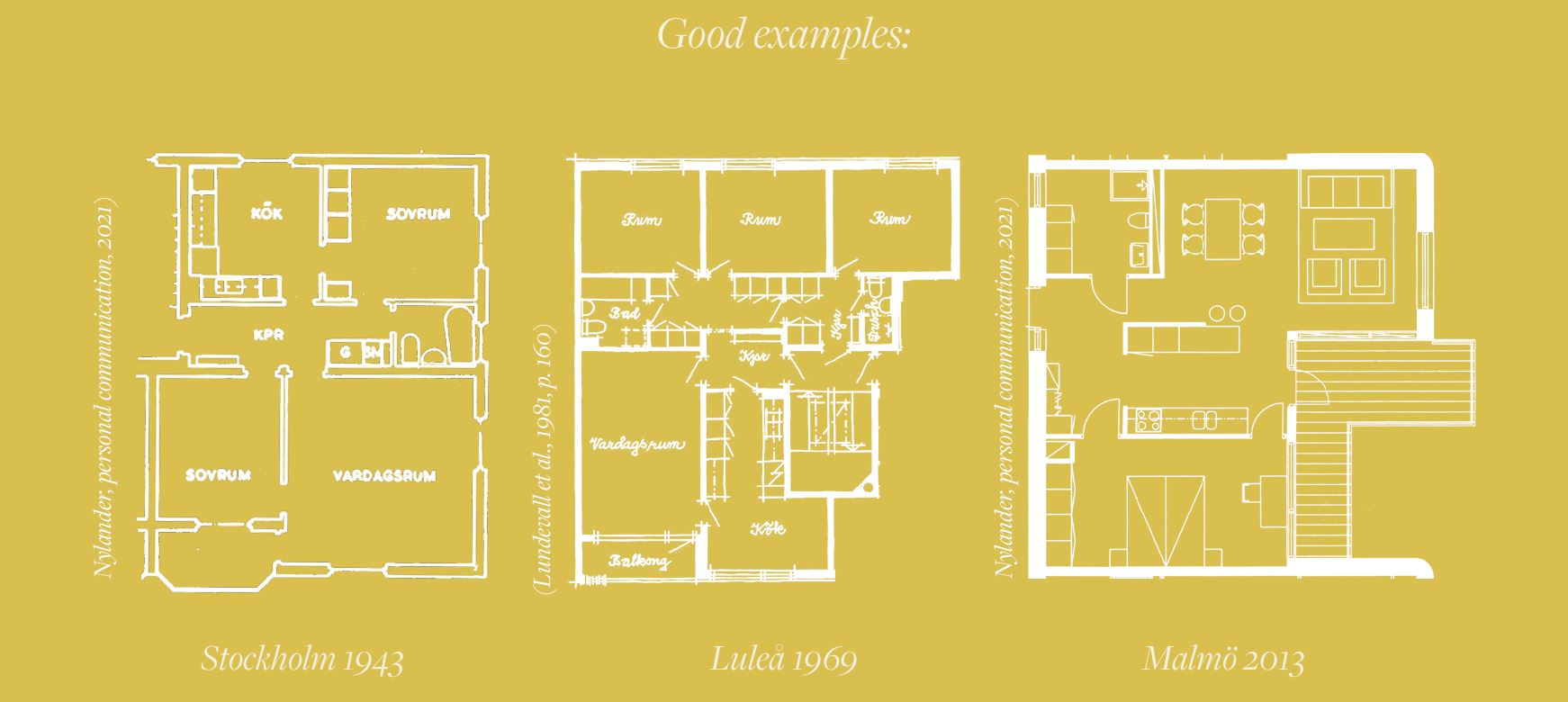

Some good examples from previous decades are from 1943, 1969 and 2013. What these three have in common despite their differences is the design of living rooms with multiple free walls, bedrooms large enough for a double bed, the possibilities to refurnish rooms and even switch functions between social and private, e.g. bedroom and living room. The dwellings’ overall design gives good conditions for furnishability and change.

In new plans from the previous five years, a lot of them are pretty compact and hard to vary and furnish. I’ve been looking at apartment plans and changed them to give them greater furnishability. I’ll now present some of the changes I’ve made.

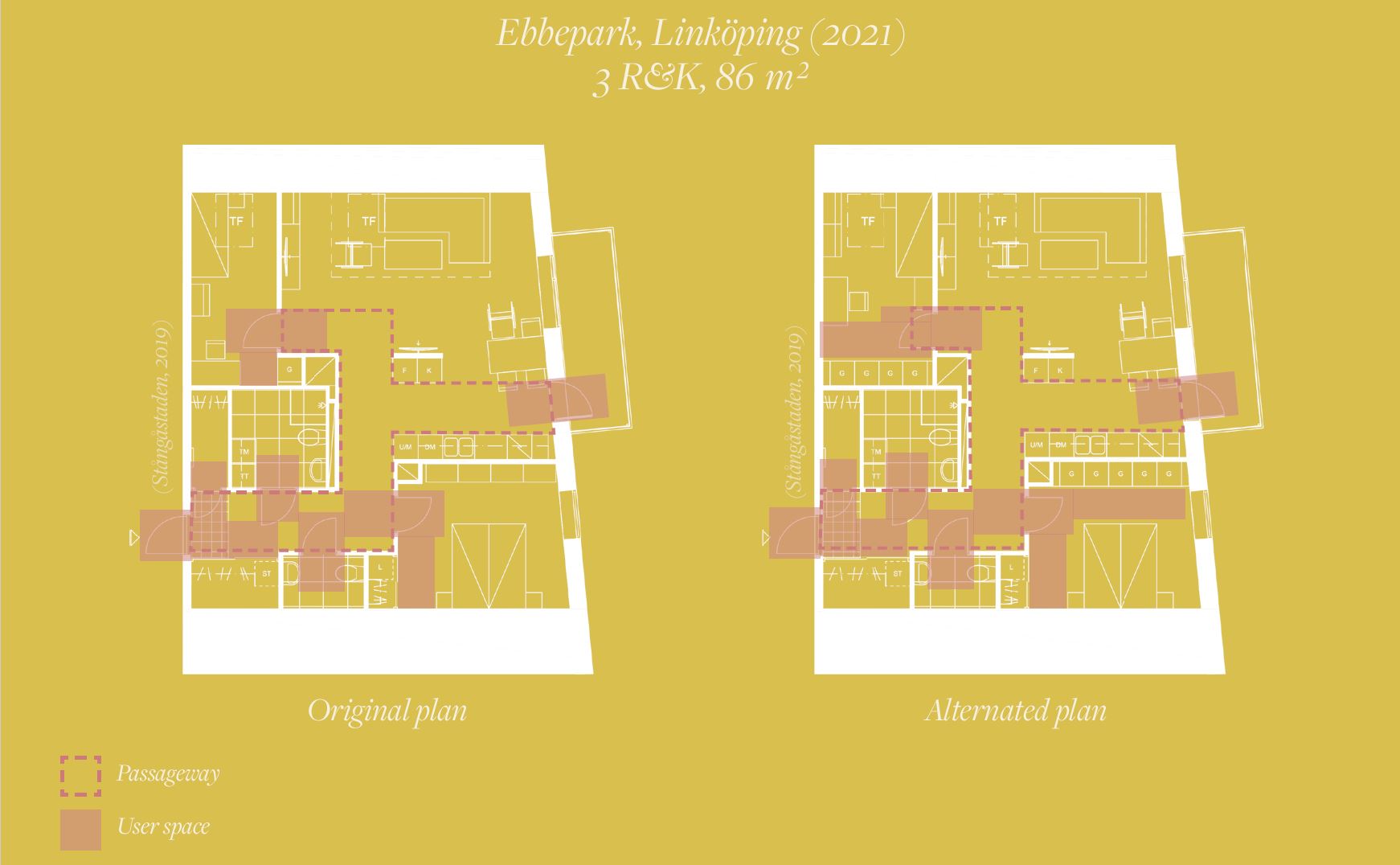

The first one is in Ebbepark in Linköping. It has an open plan solution with one larger and one smaller bedroom. The smaller one is hard to furnish and the large one lacks good spaces for wardrobes or other things. In my proposal, I’ve moved the smaller bedroom wall to give more space and to be able to furnish at least two ways. The larger bedroom is given a bit more space to be able to furnish with wardrobes, without making the kitchen less accessible.

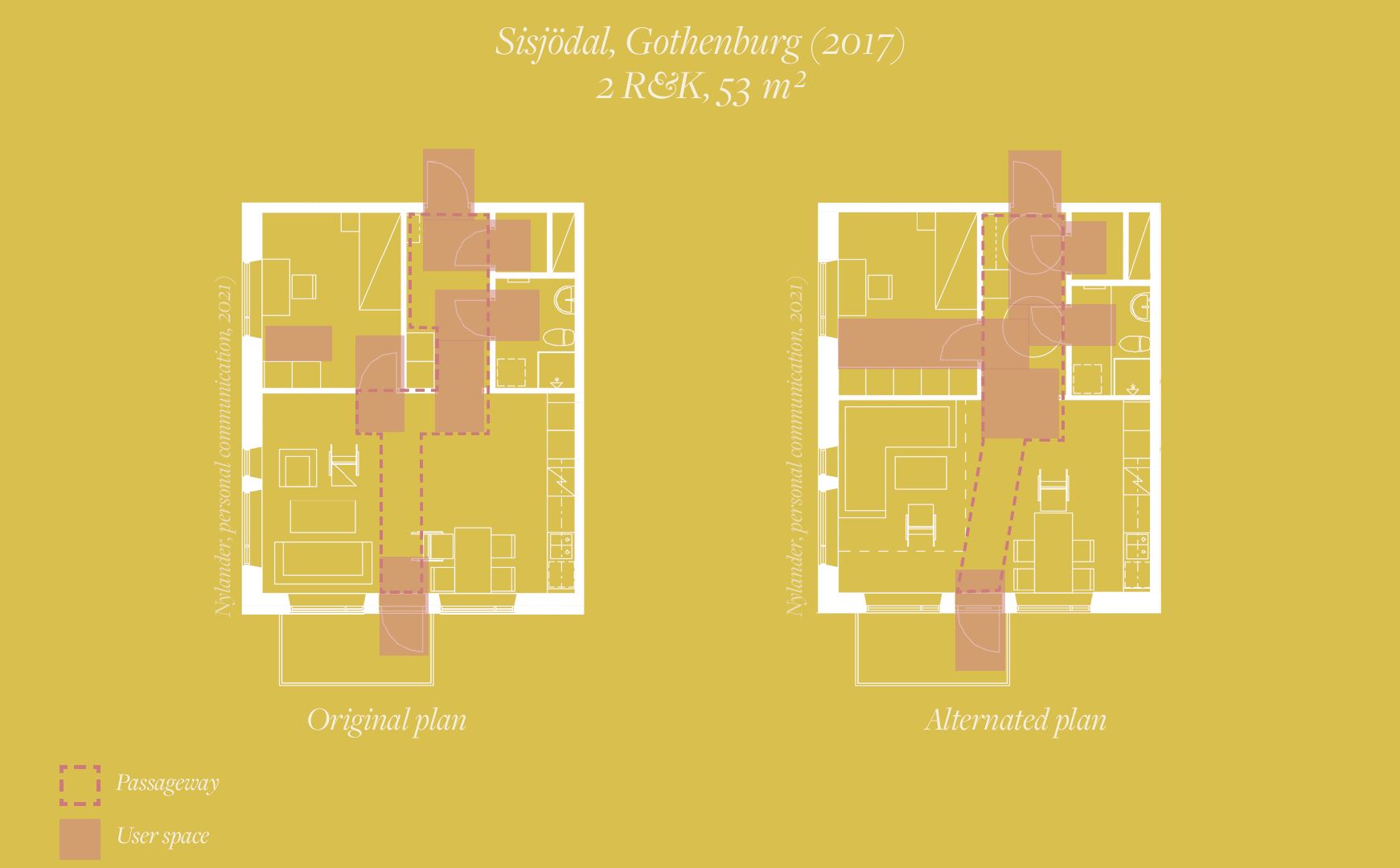

The second change is made in Sisjödal in Gothenburg. In my proposal, I’ve moved the bedroom door to the hallway instead of the living room to free up more space for furniture there. This also gives the possibility to have a whole wardrobe wall in the bedroom without taking more available space for furniture.

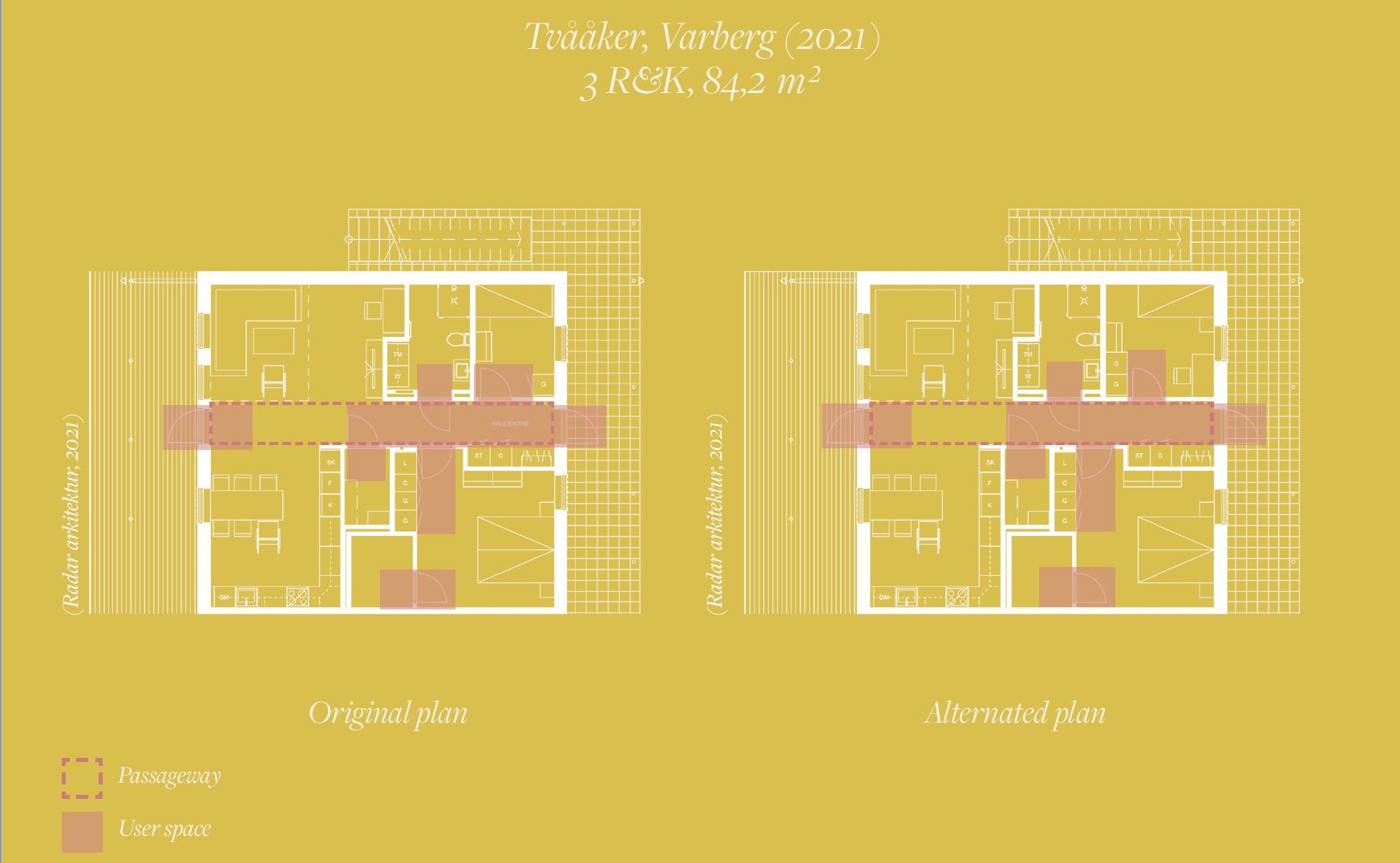

The last change I’ll show here is from Tvååker in Varberg. Just like in the first case, it is an open plan solution with two bedrooms, one smaller and one larger. The changes made are the enlargement of the smaller bedroom, where the bathroom is moved to provide the space. It can now be furnished in at least two ways, but has taken space from the living room.

The biggest reason for why it is hard to furnish and use rooms from contemporary housing is first and foremost the size. It is hard to adapt them to change, where it’s mostly larger ones that can be adapted. The housing research has to continue to develop and be implemented in future dwellings, to e.g. avoid overcrowding, unnecessary renovations and unwanted relocations. Flexibility is also important for the future needs. One example is that older people still could have a parlour, which is something less common with younger families and is starting to disappear. Societies’ view on dwellings has changed with time and still is. Through flexibility, dwellings have better preconditions to handle future use. With that, furnishability could be summarized as:

The understanding of what furniture are used and will be used in a dwelling

Making rooms large enough, preferably 2,5 times the size of the combined area of all furniture that should fit inside of it and being able to change their use

Thought through placement of openings and installations for free walls and passageways

Implementation of variation, alternate furnishings and new uses early in the design process

It is worth wondering why one has turned away from the previously made research. Some argue that the price per square meter has made dwellings smaller. The building should last at least a hundred years, why should it be poorly equipped only because of building costs? A couple of extra square meters gives more to the dwelling and its intended use. It is worth remembering that more expensive housing applies to a certain kind of user. Rentals give more people the chance to take part of the supply, that could be cheaper after the building cost is paid off.

The pandemic has shown that the dwelling has become more important for many, where most people have spent more time at home. This has given the dwelling a greater role that it wasn’t suited for. It could therefore be questioned why the dwellings are shrinking when the pandemic shows the need for more space and furniture for unknown changes.

Where the dwelling is suited for the future needs, there is also space for the furniture that could be used with it. Understanding the importance of, and implementing, furnishability gives good possibilities for a more varied use. What is loved, also lasts. This value is not only for the residents, it’s also for the dwelling, where it can have a more diverse use without the need to change. It is therefore important to assure furnishability in dwellings, where its implementation is of importance both now and in the future. That is the power of the plan!