“To design for all the senses: start with a blindfold.”

– Bruce Mau

The use of all five senses in architecture has been a topic discussed for some time. In the book The Eyes of the Skin Juhani Pallasmaa argues that vision is the dominant sense used in architectural design. Pallasmaa states that this visual domination leaves little room for our other four senses, contributing to the inhumane designs of contemporary architecture .

Similarly, Chris Downey, a blind architect, talks of how we have a tendency to design for vision, and thus, leave out those who have a visual impairment. After going blind, Downey decided to continue practicing as an architect and found that his new life state gave him knowledge about his own profession that he never would have considered otherwise.

The building type which is most associated with a multi-sensory experience is the bathhouse. This space, however, which is rich in non-visual stimuli, remains largely inaccessible to people with a visual impairment. It was in this paradox that the idea for this master thesis was born: to create a bathhouse covered in complete darkness.

The aim of this master thesis was to create a bathhouse filled with experiences for the non-visual senses. The main sense investigated in this thesis has been the sense of touch, looking at how it can contribute to the architectural experience. The design of the bathhouse has been created by using an iterative loop where knowledge informs the design. Thus, the design has been continuously re-evaluated through interviews, experiments and design studies.

The result of this thesis is in part a design where the visual experience of architecture is no longer at the top of the hierarchy, and in part an experimentation of what it is like to design without focusing on the visual output. It has provided examples for how tactility can contribute to new types of spaces, where the reach of the body and the distribution of our nervous system inform the design.

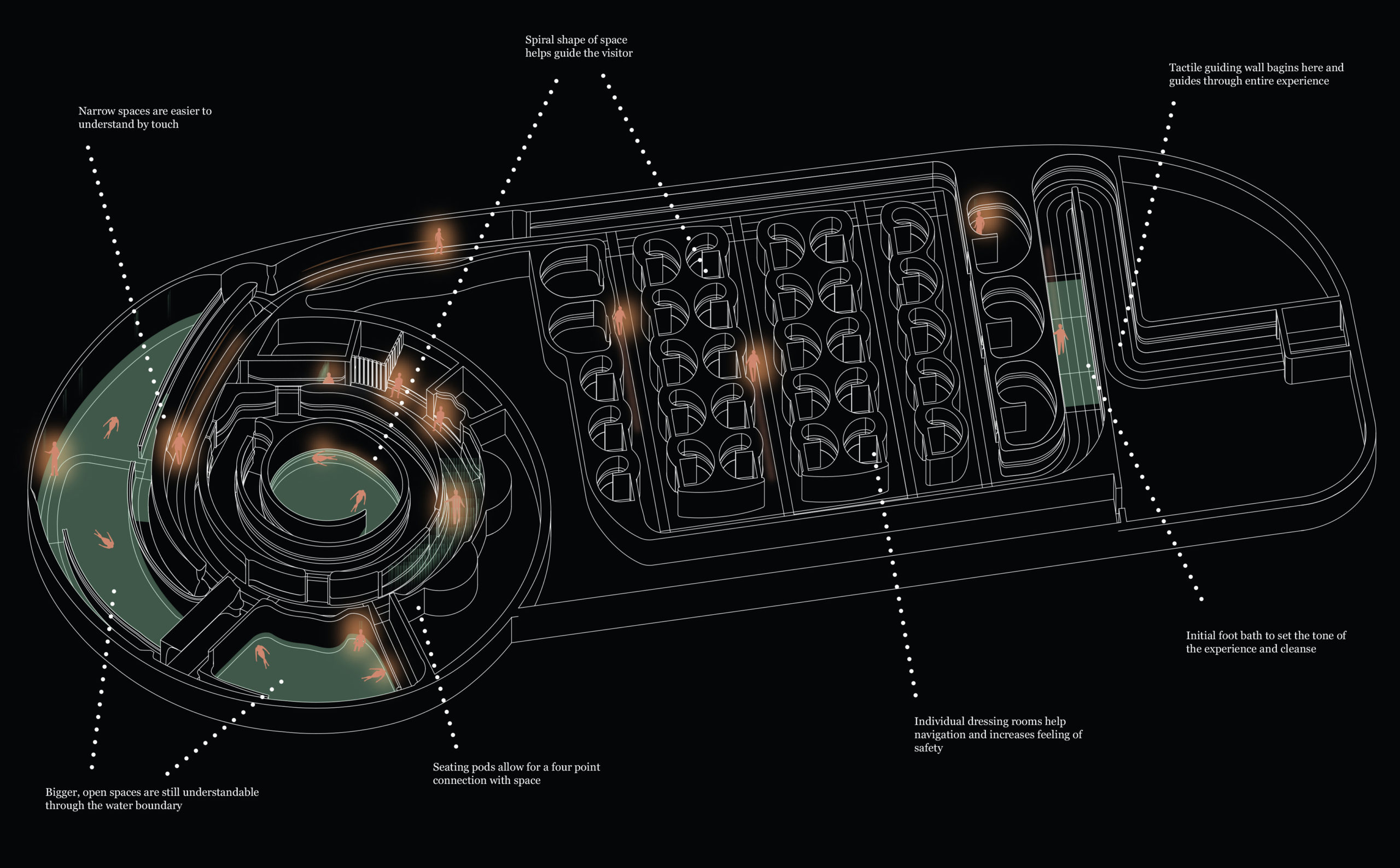

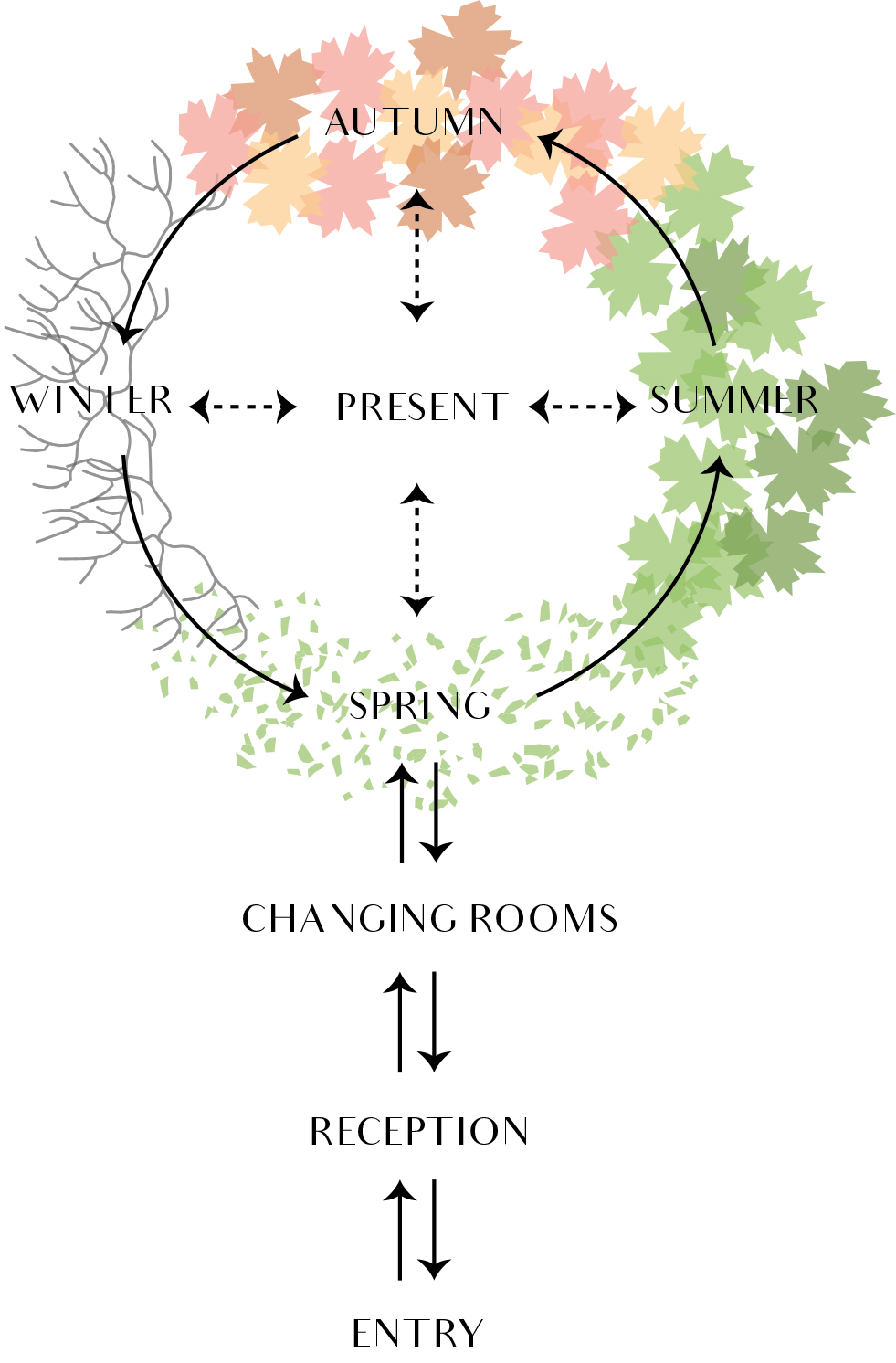

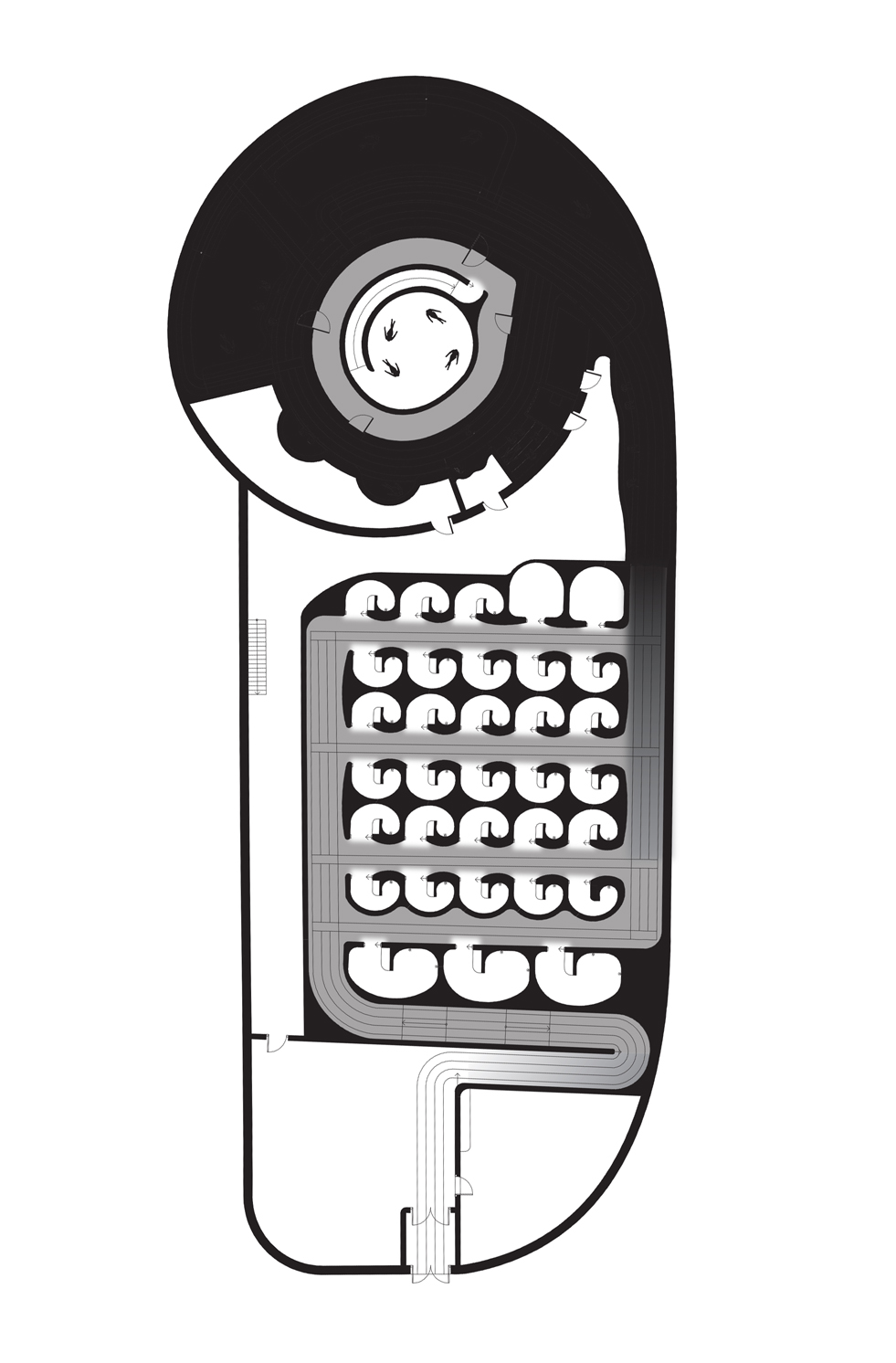

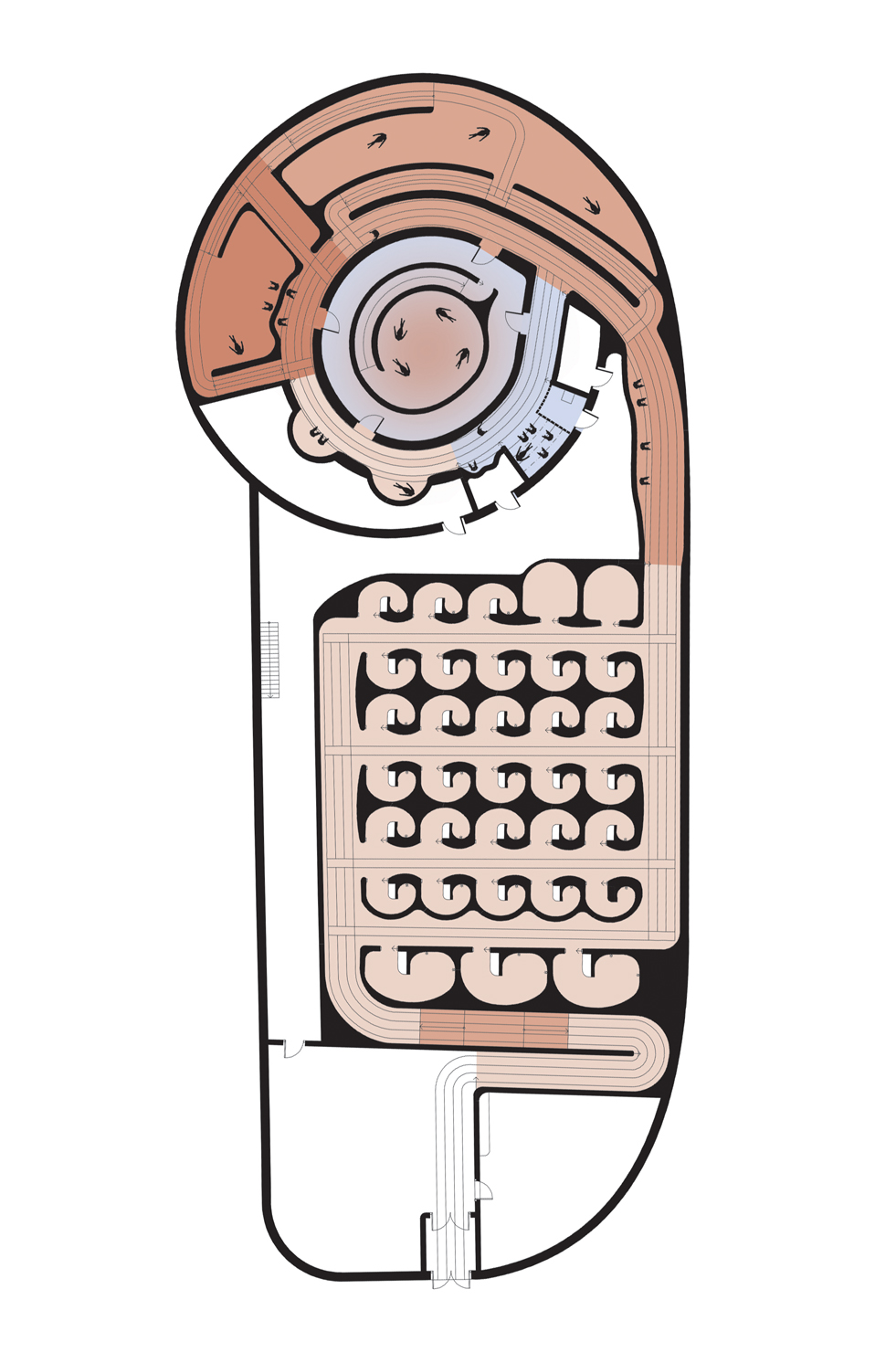

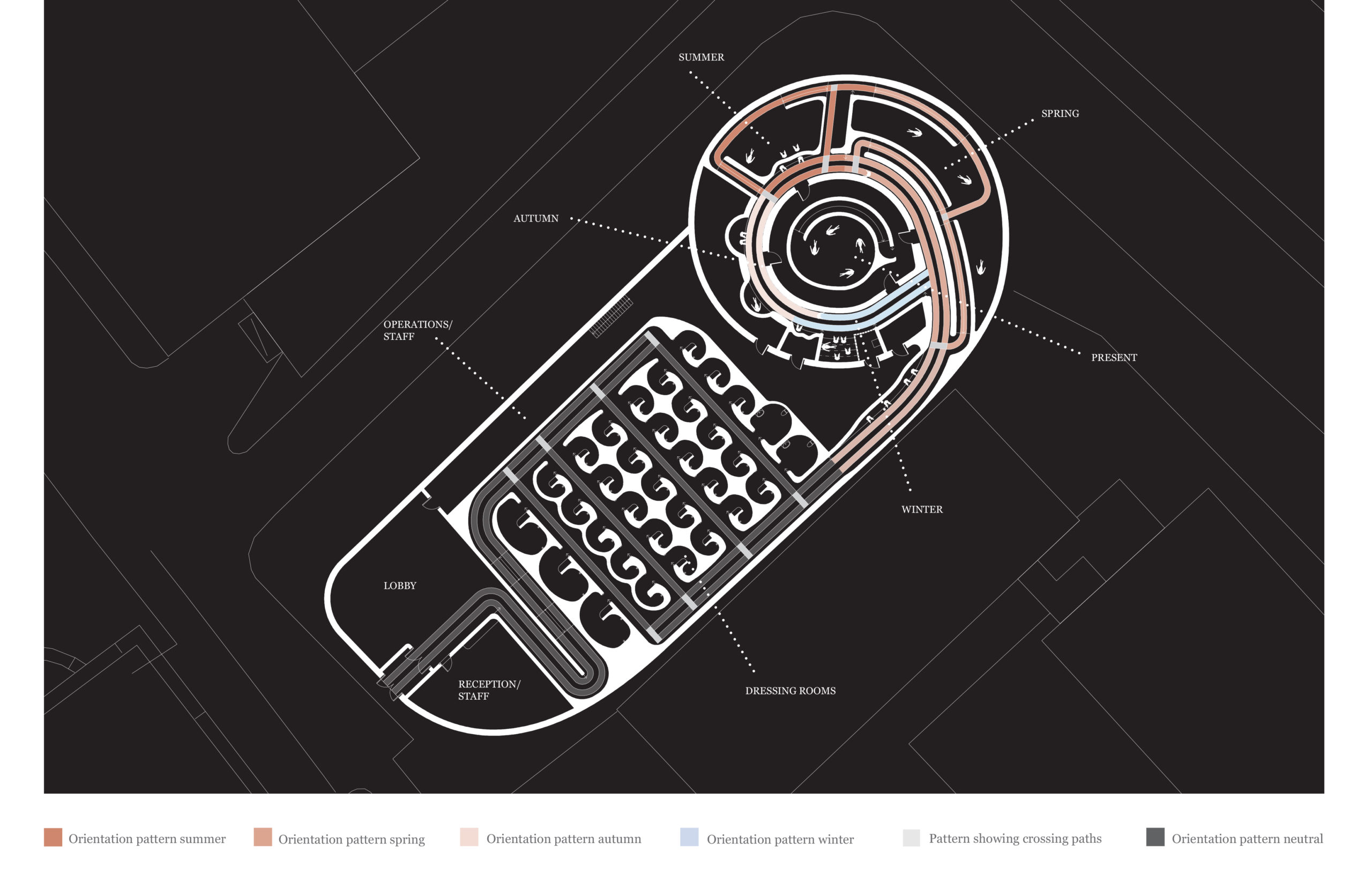

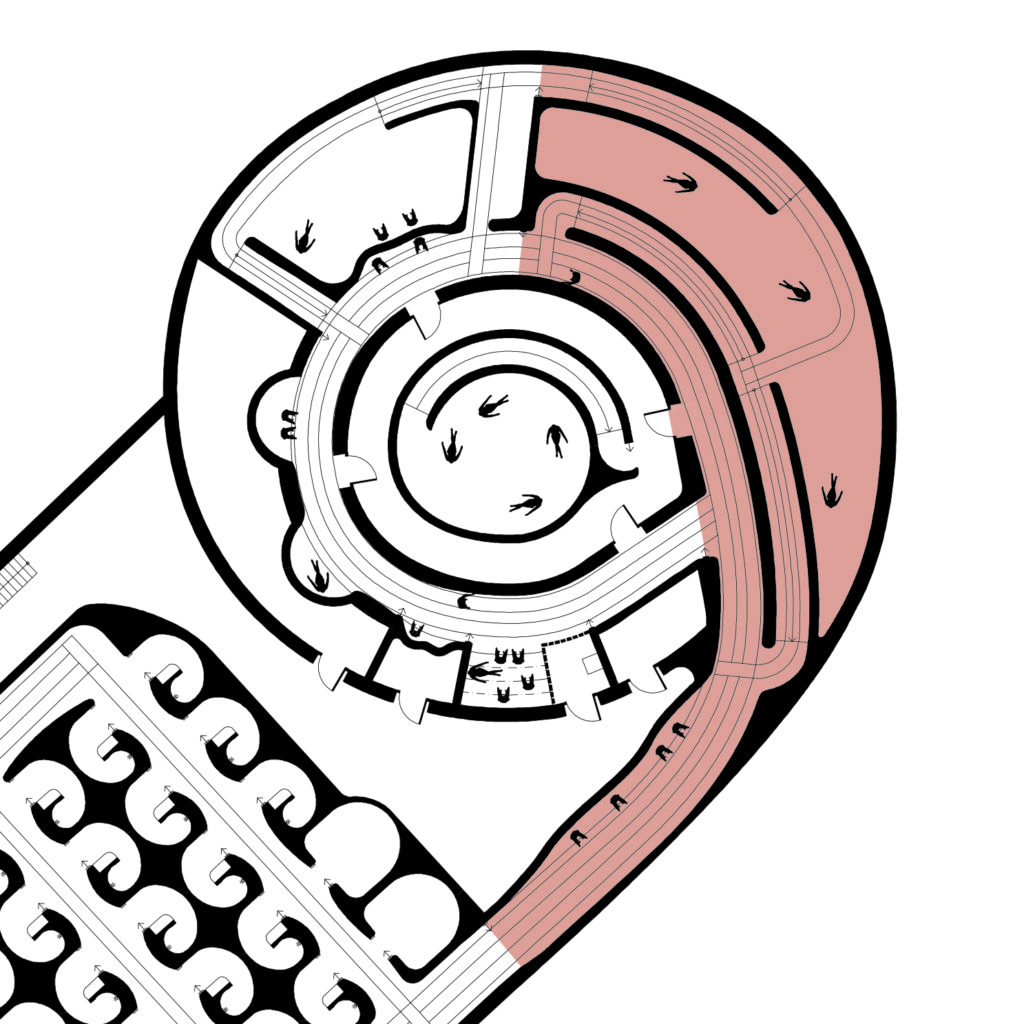

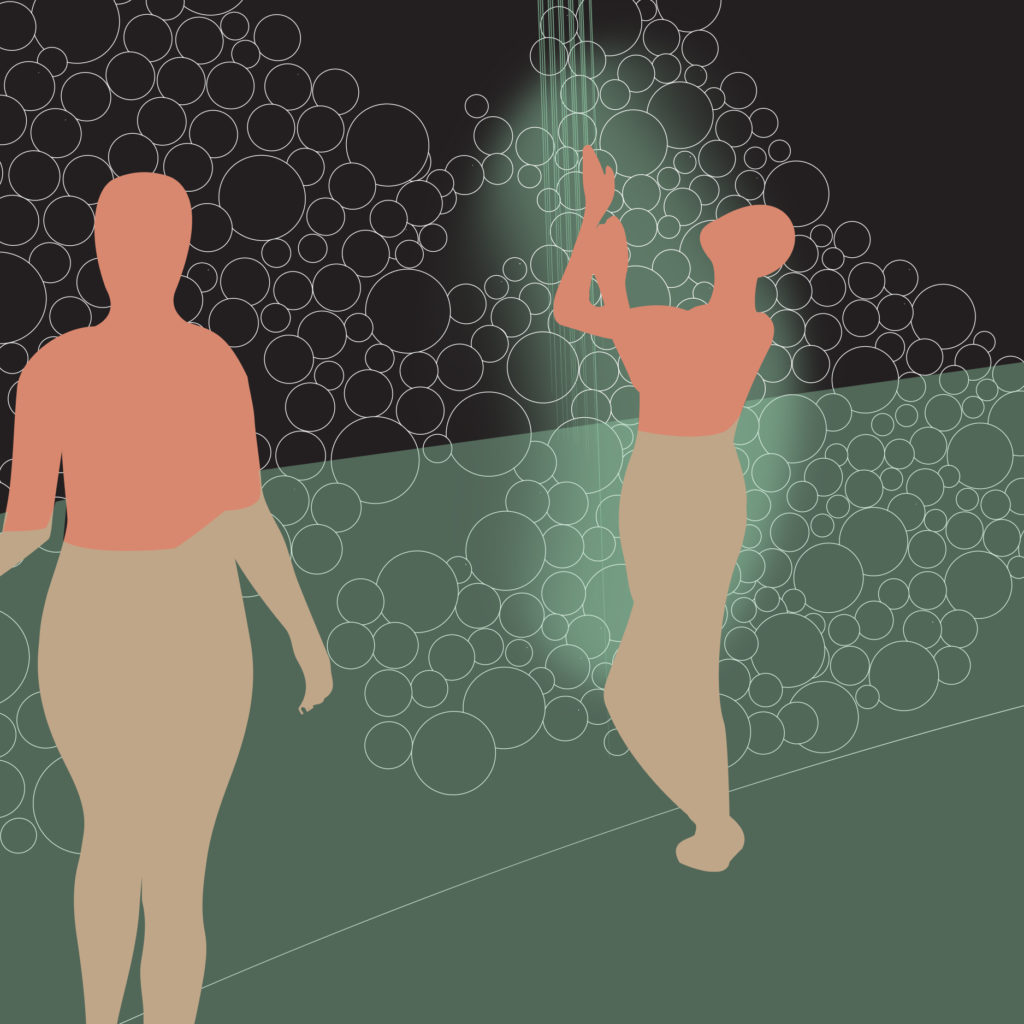

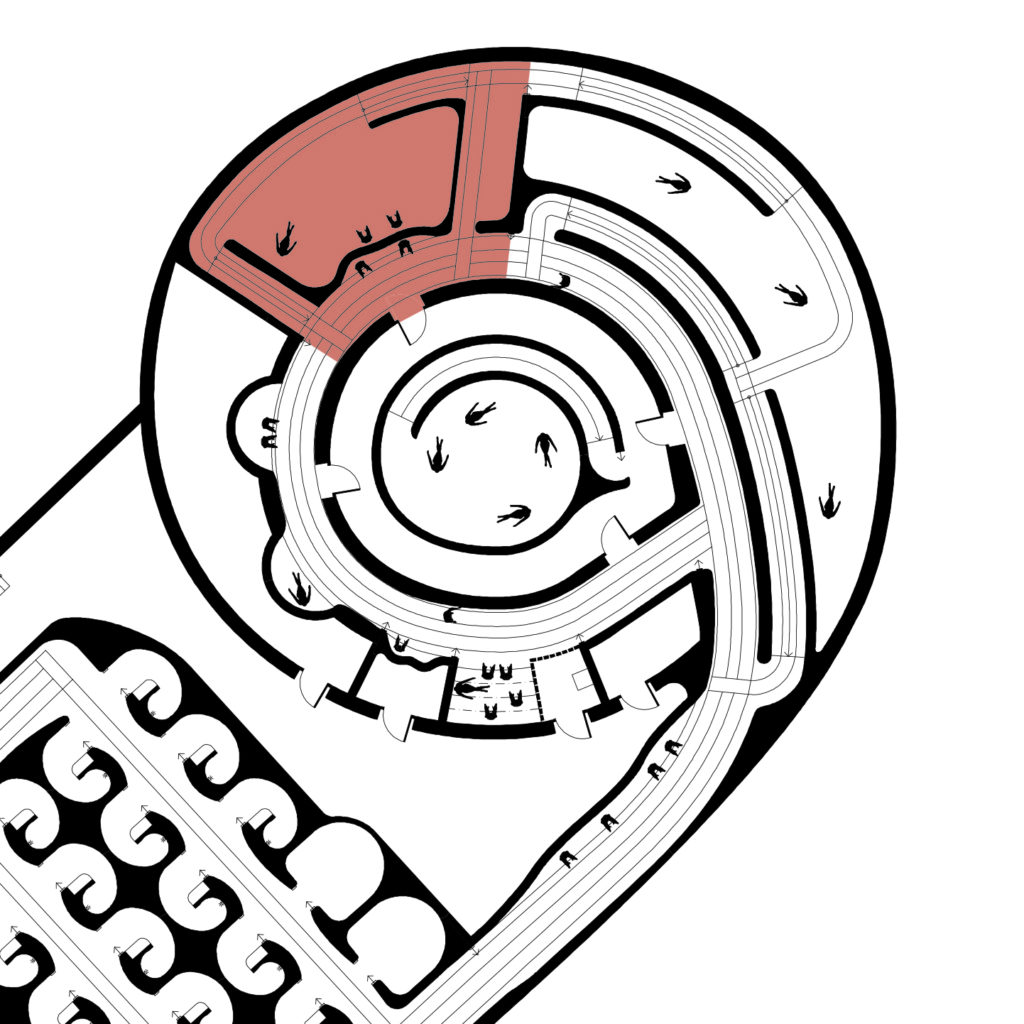

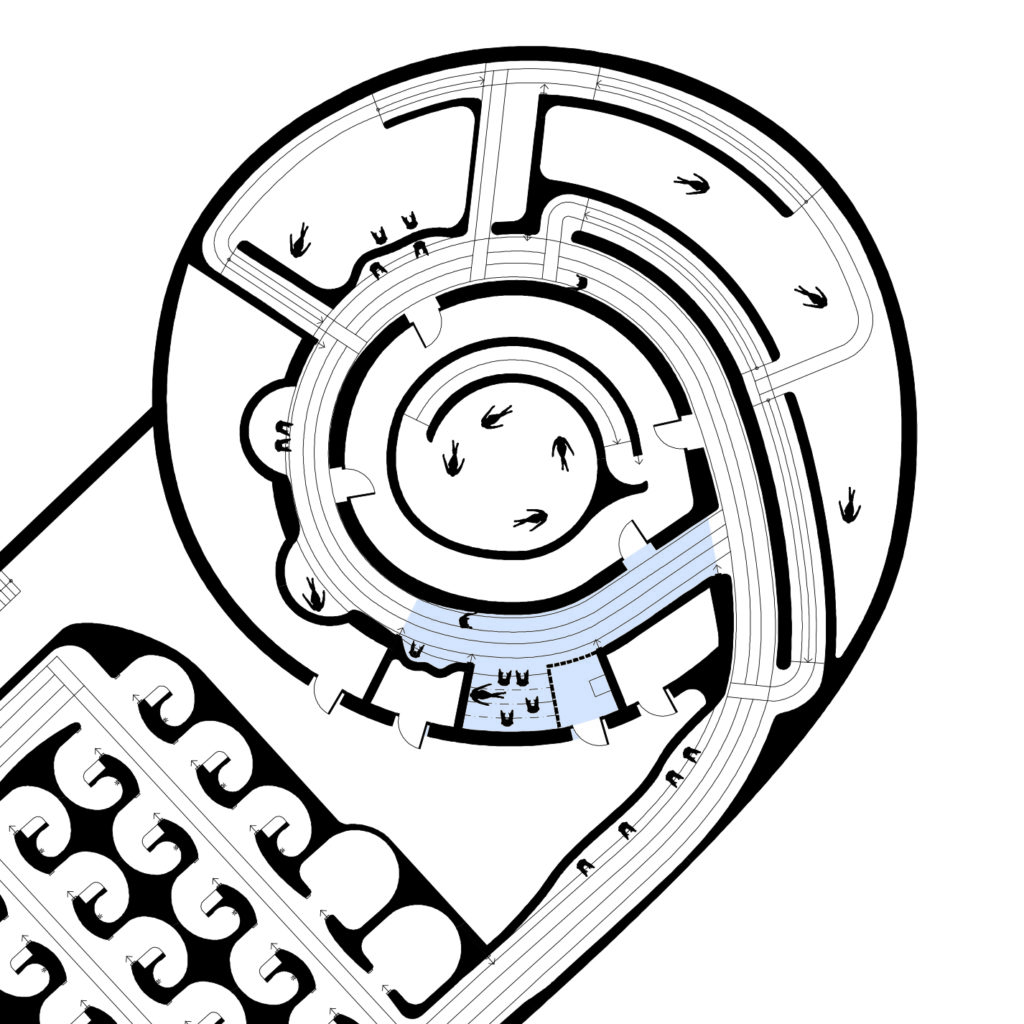

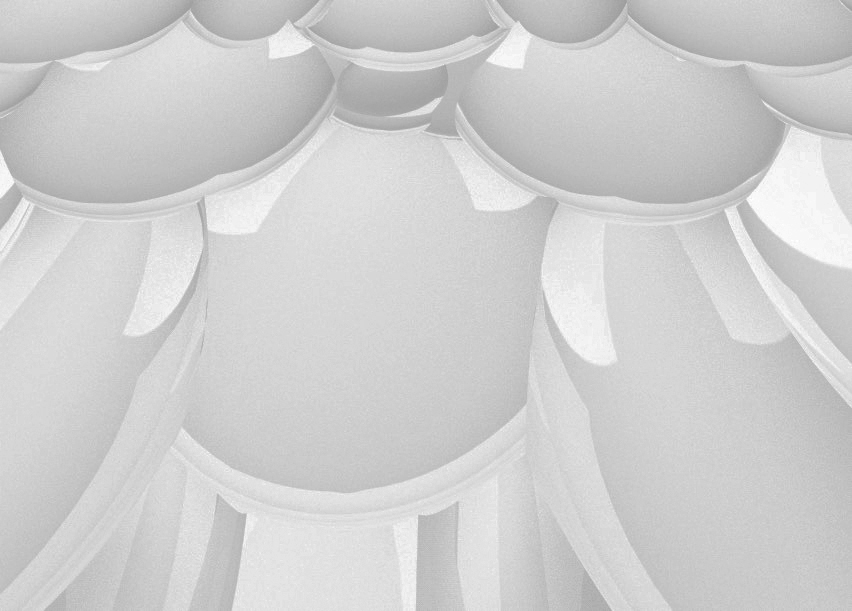

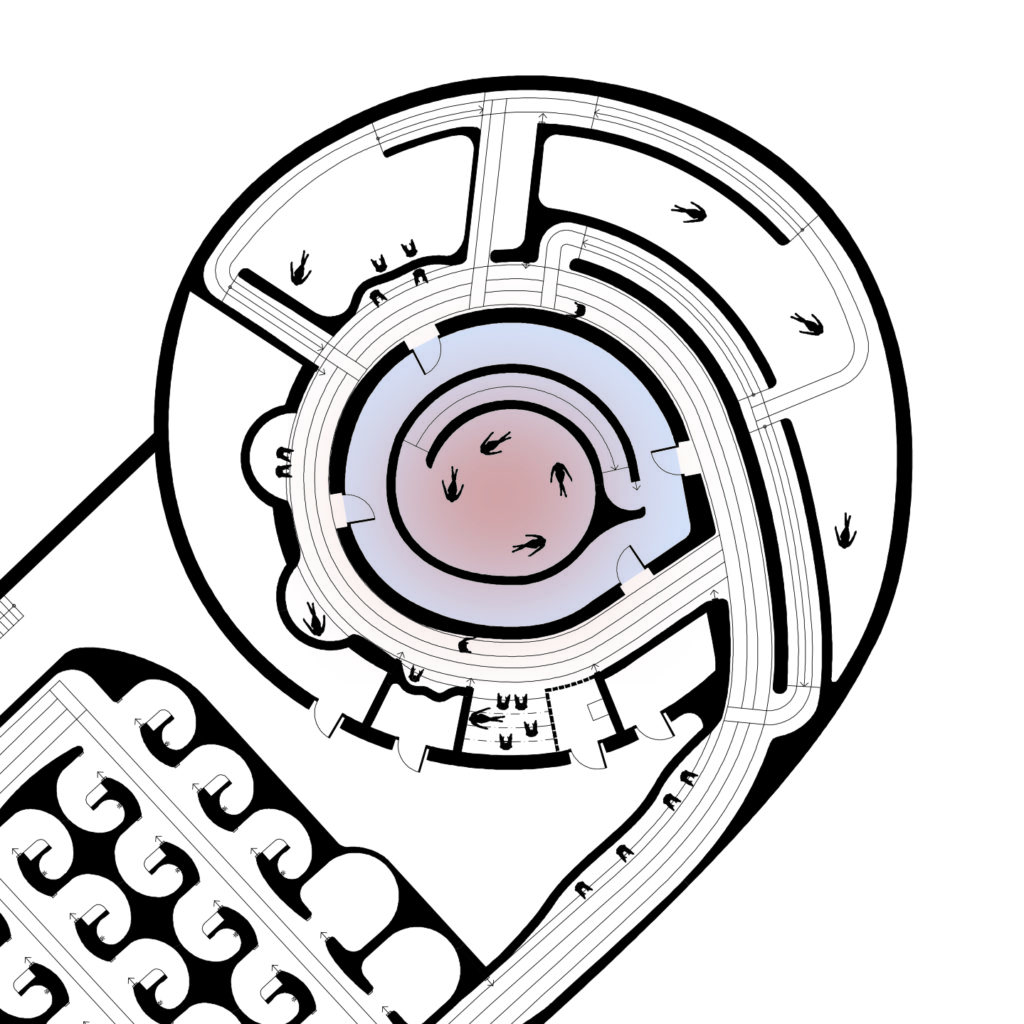

Blind Trust proposes a space for inner reflection. The enclosed building allows the visitor to release their connection to everyday life and get encapsulated by the metaphorical forest inside. This feeling of releasing the ordinary routine is further enhanced by the complete darkness in the spaces of the bath ritual. The concept for the spa is A Year in the Forest, and going through the circular path of the bathing ritual, the visitor has the opportunity to experience all seasons within a year – beginning in the budding of spring and going all the way down to the chill of winter. Each season has its own tactile patterns, giving the visitor a range of haptic experiences as they pass through a year in the forest.

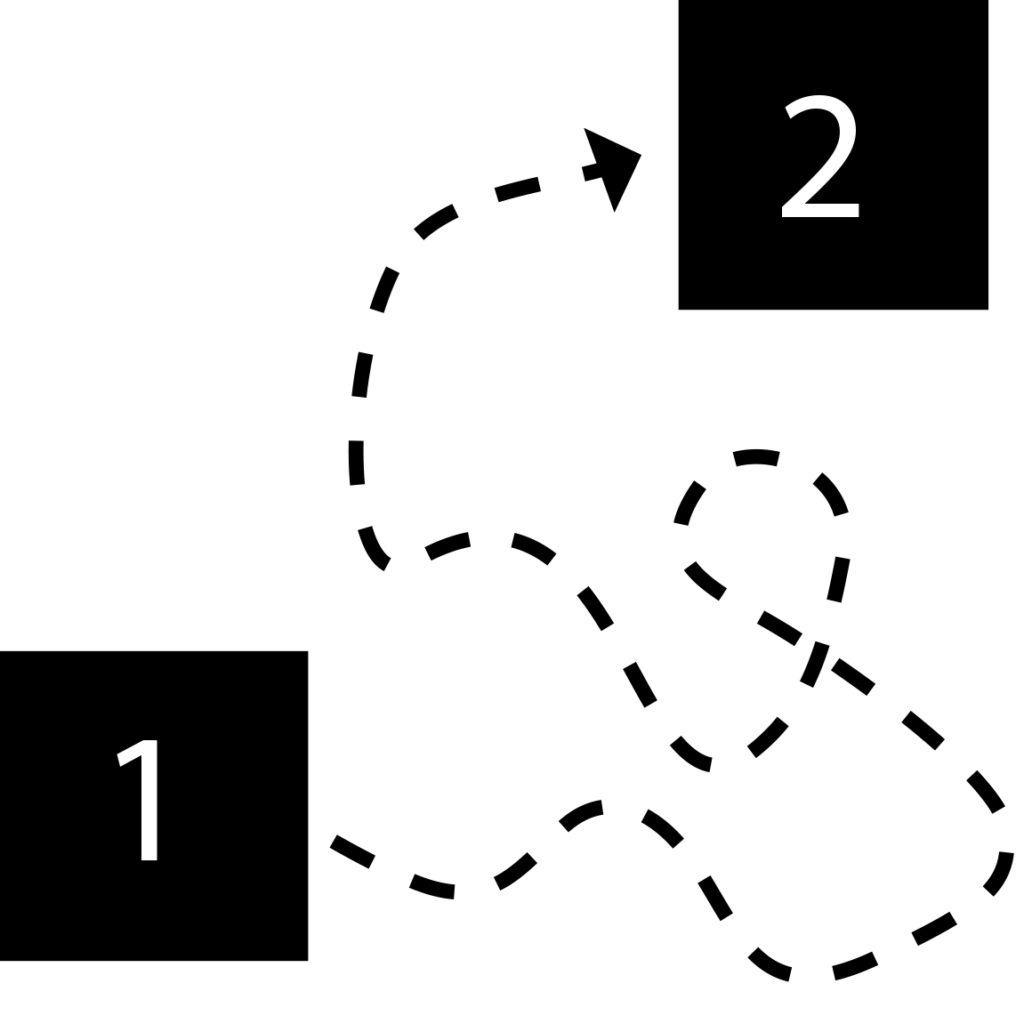

A guided path along the bathing ritual was important, while maintaining the option for a more free path. The visitor can choose to follow the circular path, going through all seasons in order, or create their own path using the central pool which connects the different zones.

The darkness inside the bath greets the visitor gradually.

The different temperature zones of the bath. Darker colour shows higher temperatures.

SPRING

From the dressing room the visitor walks through a gradually darker corridor before entering the completely dark bath experience. Here they are greeted by the area of spring. Through the warm space there is a scent of flowers, coming from the pool which has been filled with small petals. Along one of the walls a water stream is trickling down, creating sounds as it travels along the wall. The visitor is guided down into the pool via a ramp, gradually being immersed in the warm water.

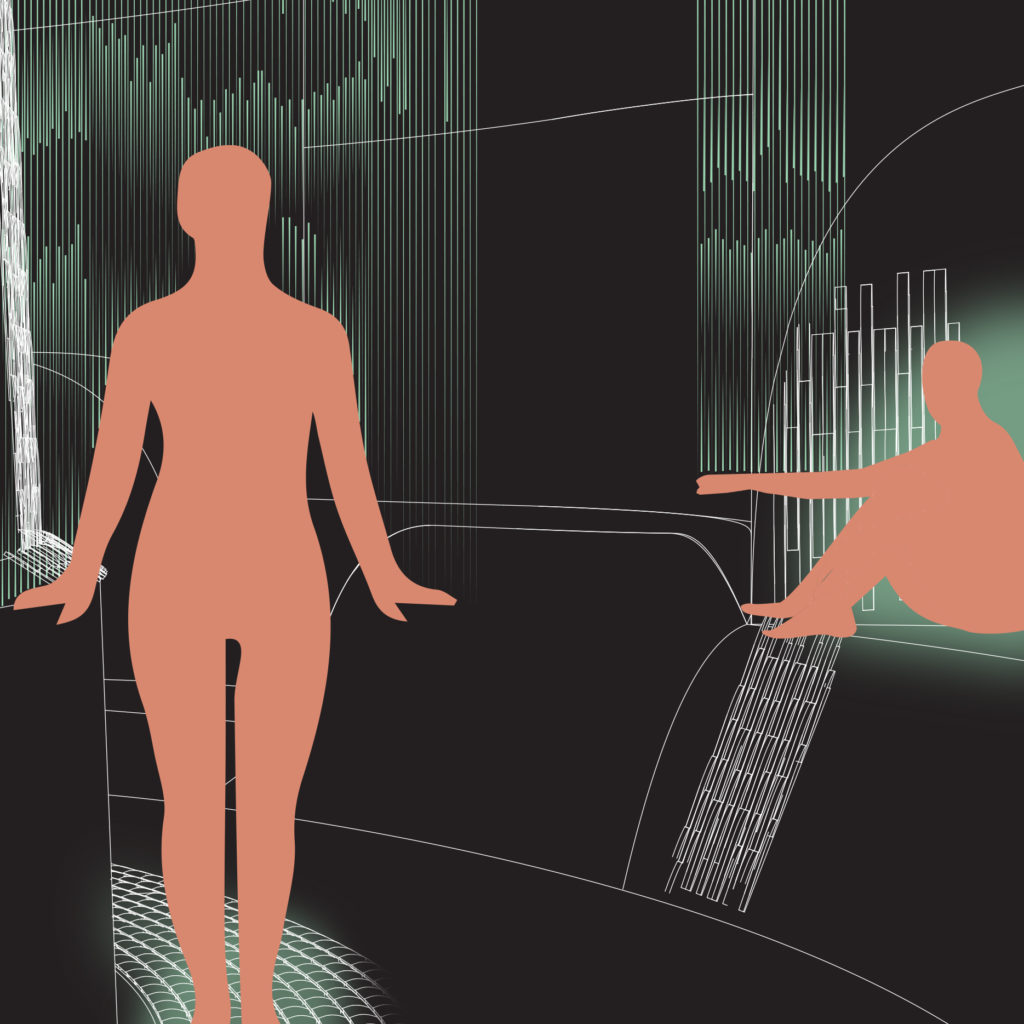

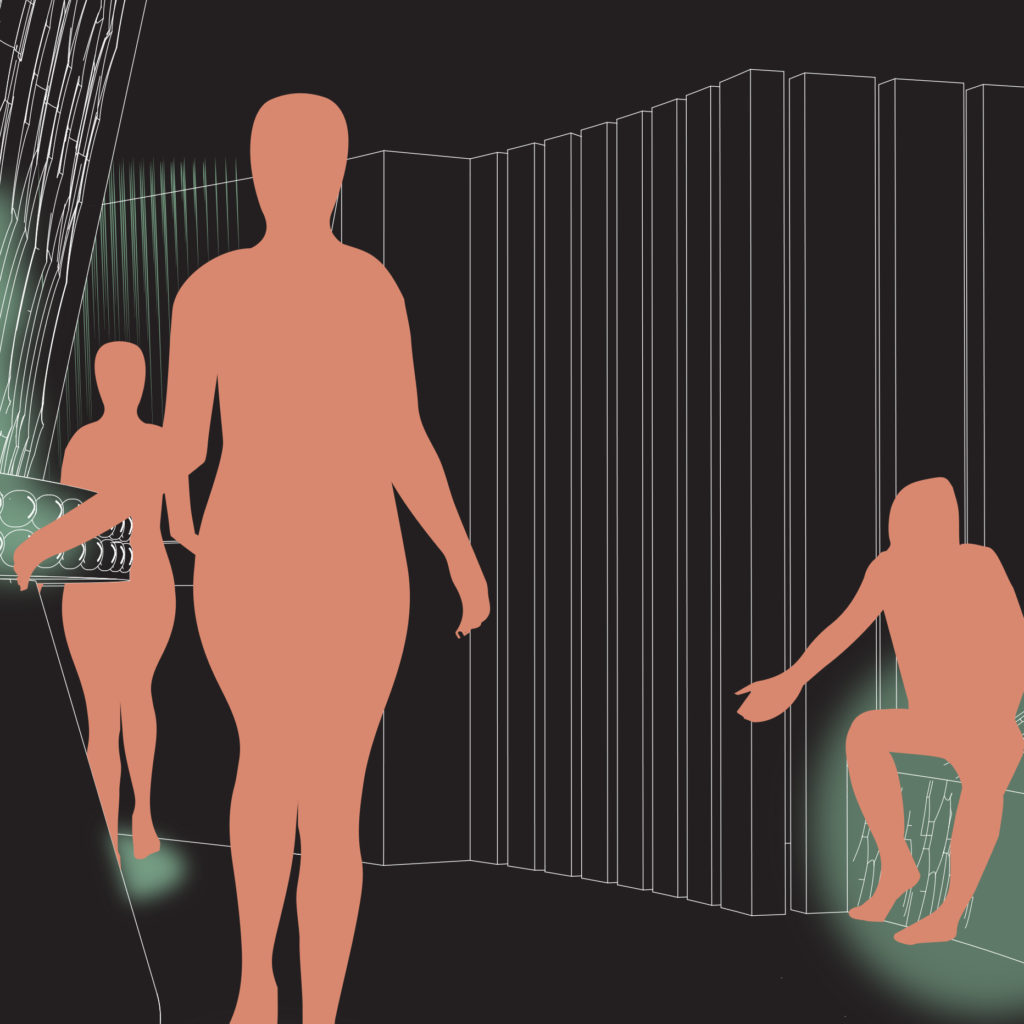

Perspective of spring area

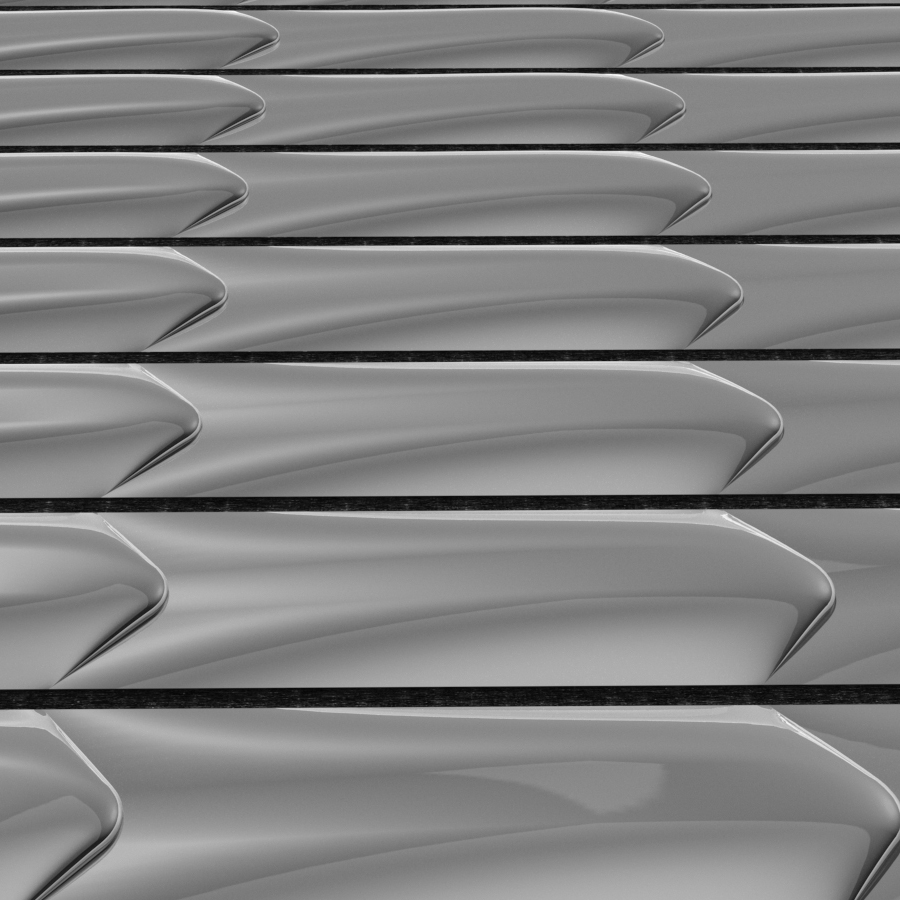

Tactile trail pattern for spring area

Wild pattern for spring area

SUMMER

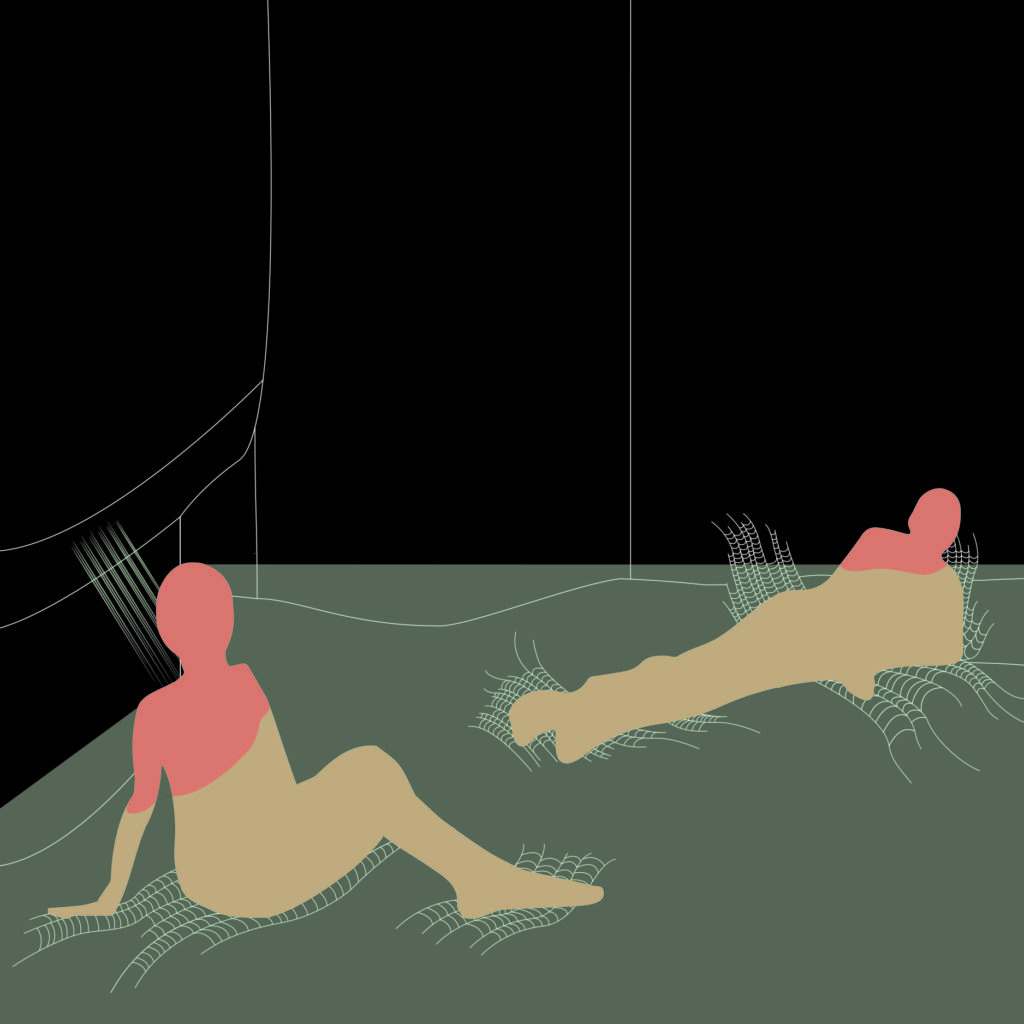

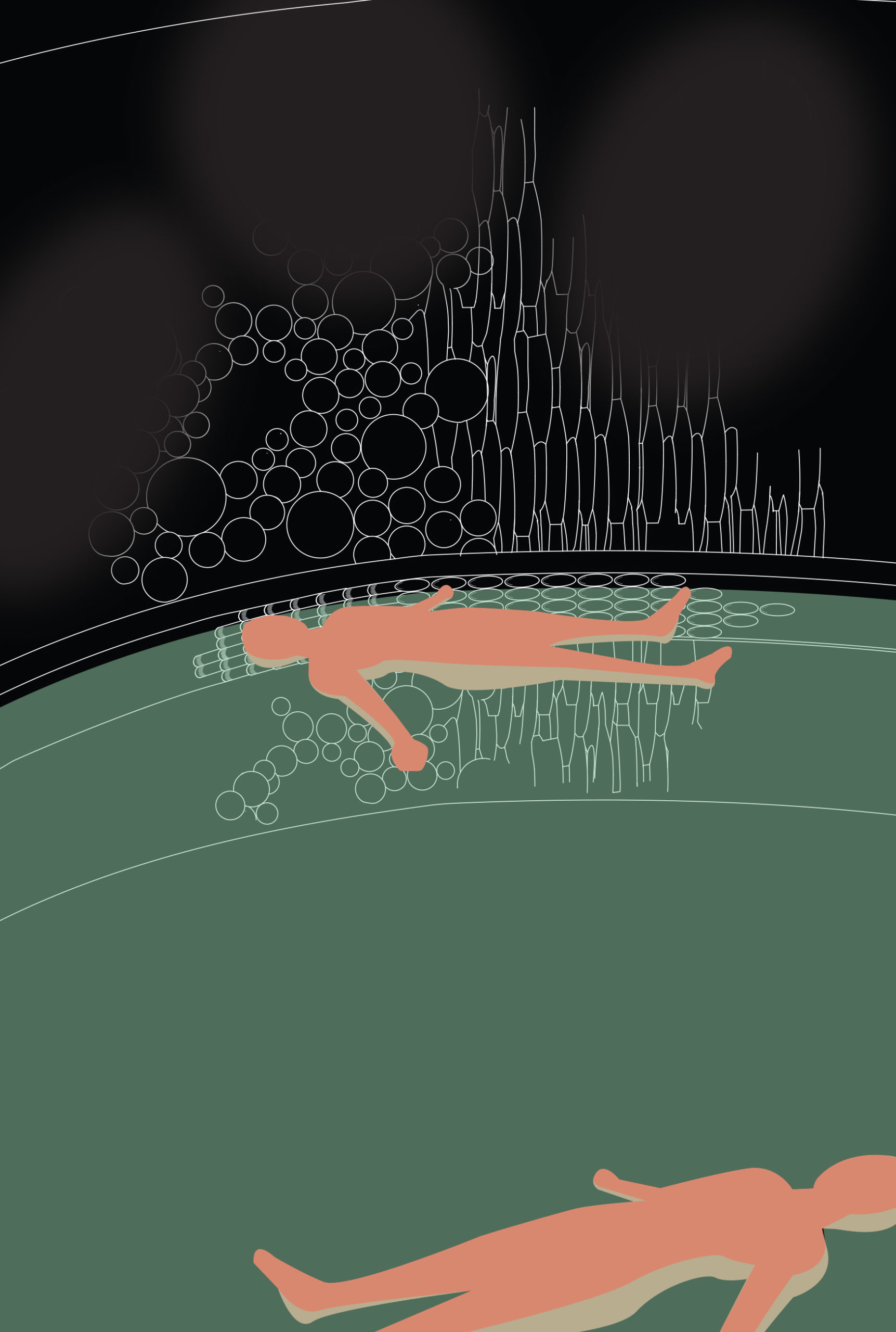

After passing through spring, the visitor is guided into the heat of summer where a ramp leads into the hot pool inside the space. The pool is shallow, with a water level between 350 mm and 600 mm, making it the perfect pool for the visitor to sit or lie down in, while enjoying a back or foot massage from the jets placed in the pool.

Perspective of summer area

Tactile trail pattern for summer area

Wild pattern for summer area

AUTUMN

Having walked through summer, the visitor continues their path into autumn where they enter into a room full of rain. A steady stream of water falls from the ceiling down on the passing visitors and their surroundings. Along the path there are pods where the visitor has the opportunity to stay and listen to the drumming of the rain.

Perspective of autumn area

Tactile trail pattern for autumn area

Wild pattern for autumn area

WINTER

The final space to enter along the circular route is the season of winter. At the beginning of this space there is a cold area, which in turn leads to a hot sauna. In the sauna there is the possibility to stay and heat up, before going into another section with a colder space. Along the path of this space the visitor will pass through a cold shower, a stark contrast to the hot sauna, before leaving winter and returning to the warm space of spring, where the visitor is once again greeted by the smell of flowers.

Perspective of winter area

Tactile trail pattern for winter area

Wild pattern for winter area

PRESENT

In the centre of the bathing area there is an outdoor pool. This pool creates a connection between the different seasons, both in the way it allows for visitors to pass straight from summer to winter, or autumn to spring, and in the way that it always represents the season of the present time during the visit. In the pool, which contains the patterns of all four seasons, the visitor can float along a circulating stream – a reflection of the circular motion of the ritual inside.

The following studies were made throughout the project. Not all observations are documented here on the website. For a full recount see the booklet at the bottom of the page.

INVESTIGATION 1 – BLIND WALKS

This investigation was conducted by walking through four bathhouses twice: once with eyes closed and once with eyes open. The aim was to reflect on how the sensory experience of a bathhouse changes when the visual input is taken away.

RESULT

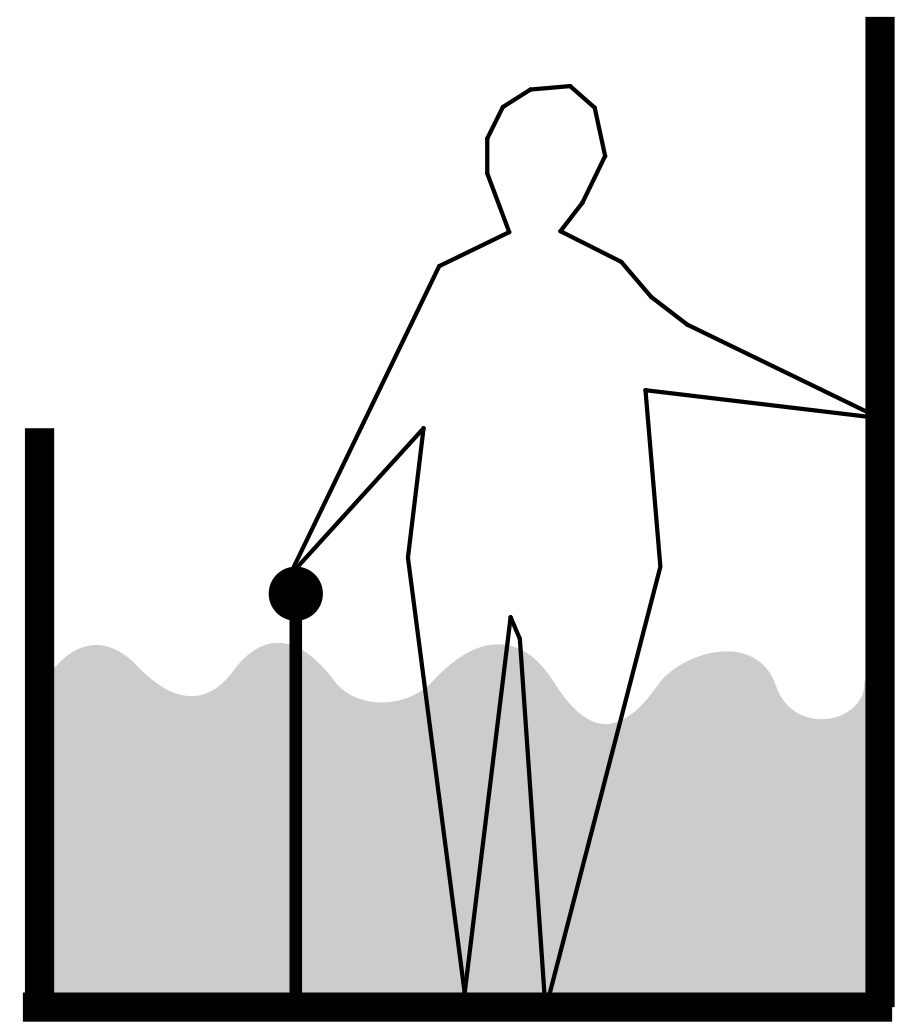

Several observations were made during the walks. For a full recount of the results see the booklet at the bottom of the page. The image to the left depicts one of the many observations and shows that in order to feel safe in a space it needs to feel like it’s not just one big open room. This does not necessarily need to be fixed by walls, but can be done, for instance, through a connection to a railing.

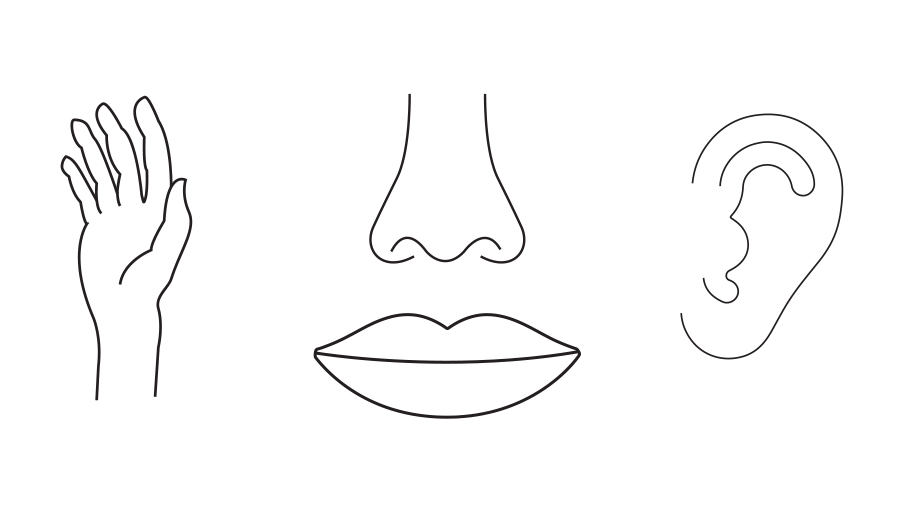

INVESTIGATION 2 – DOCUMENTATION OF TOUCH

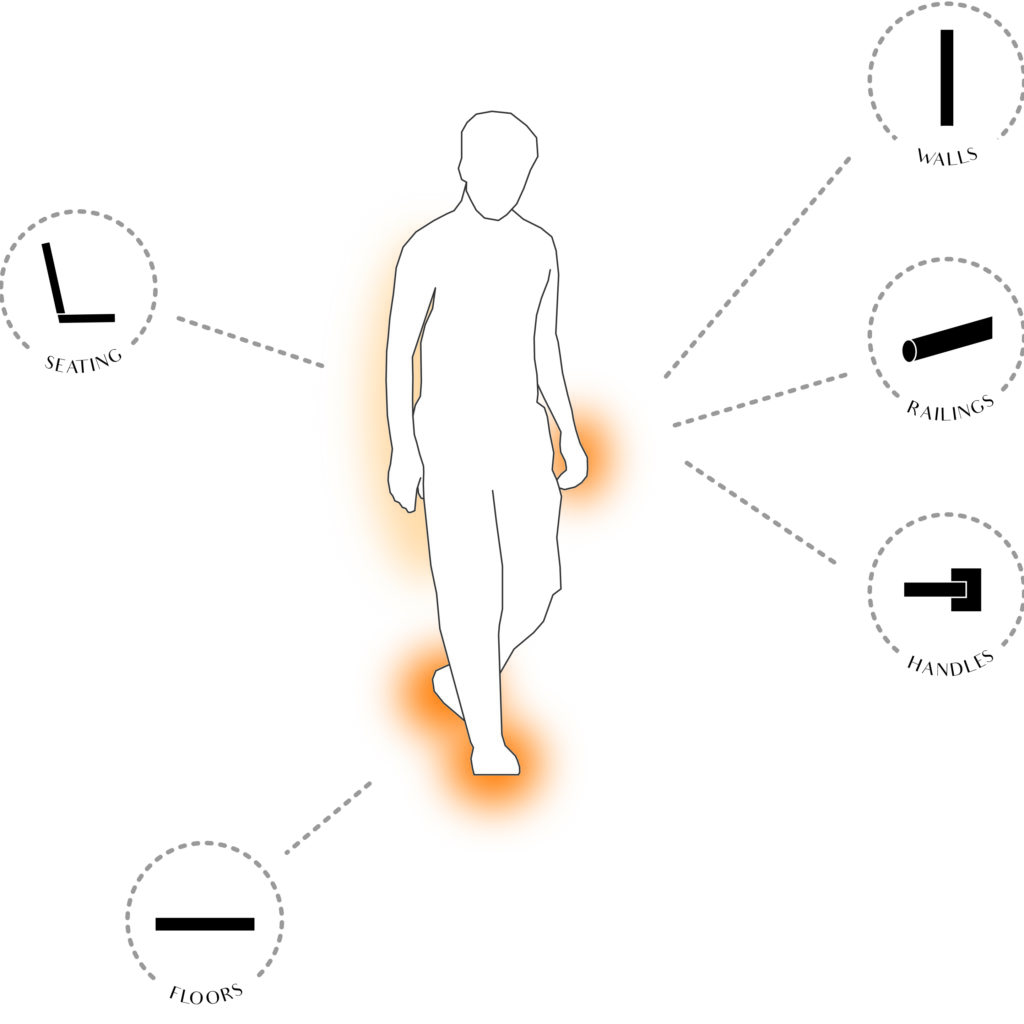

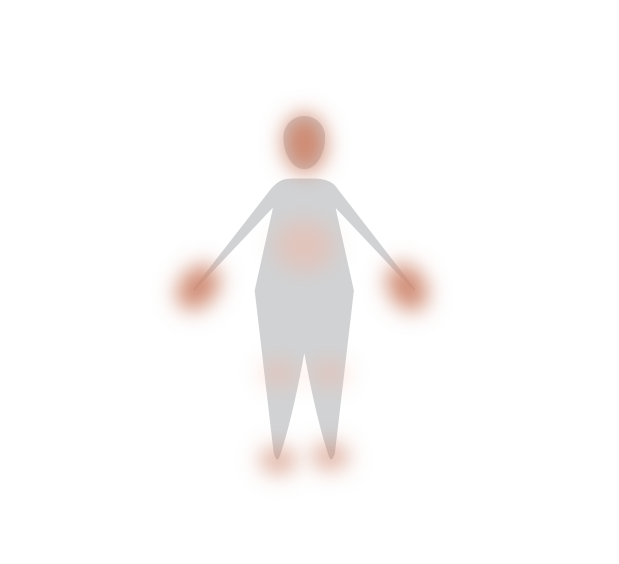

This design investigation was made by walking through a bathhouse and documenting everything that was touched. A sighted walk and a blind walk was compared to each other.

RESULT

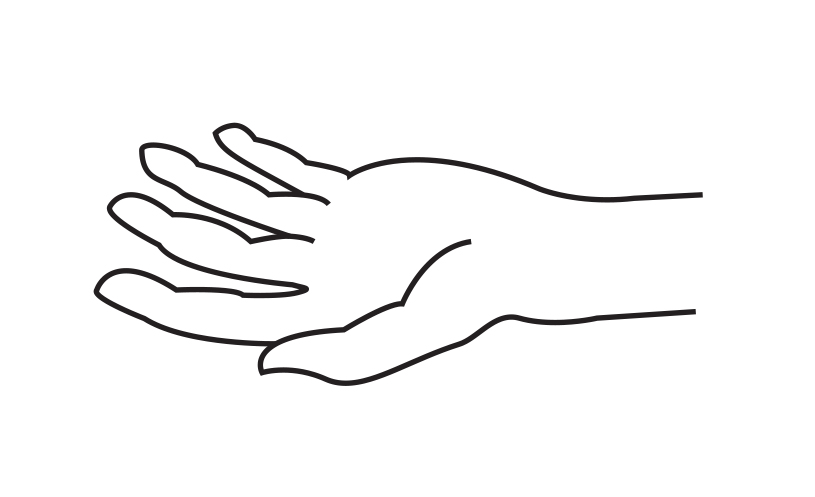

Both during the blind and the sighted experiment the main touch points between body and architecture came through feet, closely followed by hands. Hands were used frequently during both walks, but were used in higher frequency once vision was taken away. While blinded, the hands were used like haptic eyes, searching for spatial borders and information regarding the room. Thus, during the second walk, walls were touched with a higher frequency than during the sighted walk. Other connection points for the hands were handles, hand rails and shower knobs.

INVESTIGATION 3 – INTERVIEWS

Three people were interviewed, all of whom have a sight disability. The interviews were conducted one on one and were done in the form of qualitative semi-structured interviews. The aim was to gather input regarding how people with sight disabilities experience space as well as their view on the bath experience.

RESULT

Many observations were made during the interviews (for a full recount see the booklet), some of which were that:

– Navigation of the building, both towards the building and inside of the space, was touched upon several times during all interviews.

– Tactile trails were mentioned several times by all participants.

– Organization of functions was commonly talked about.

– Circulation was a common topic in all the interviews.

– Acoustics and tactility was mentioned by all participants.

– Contrasts in tactility, acoustics and experiences were mentioned several times.

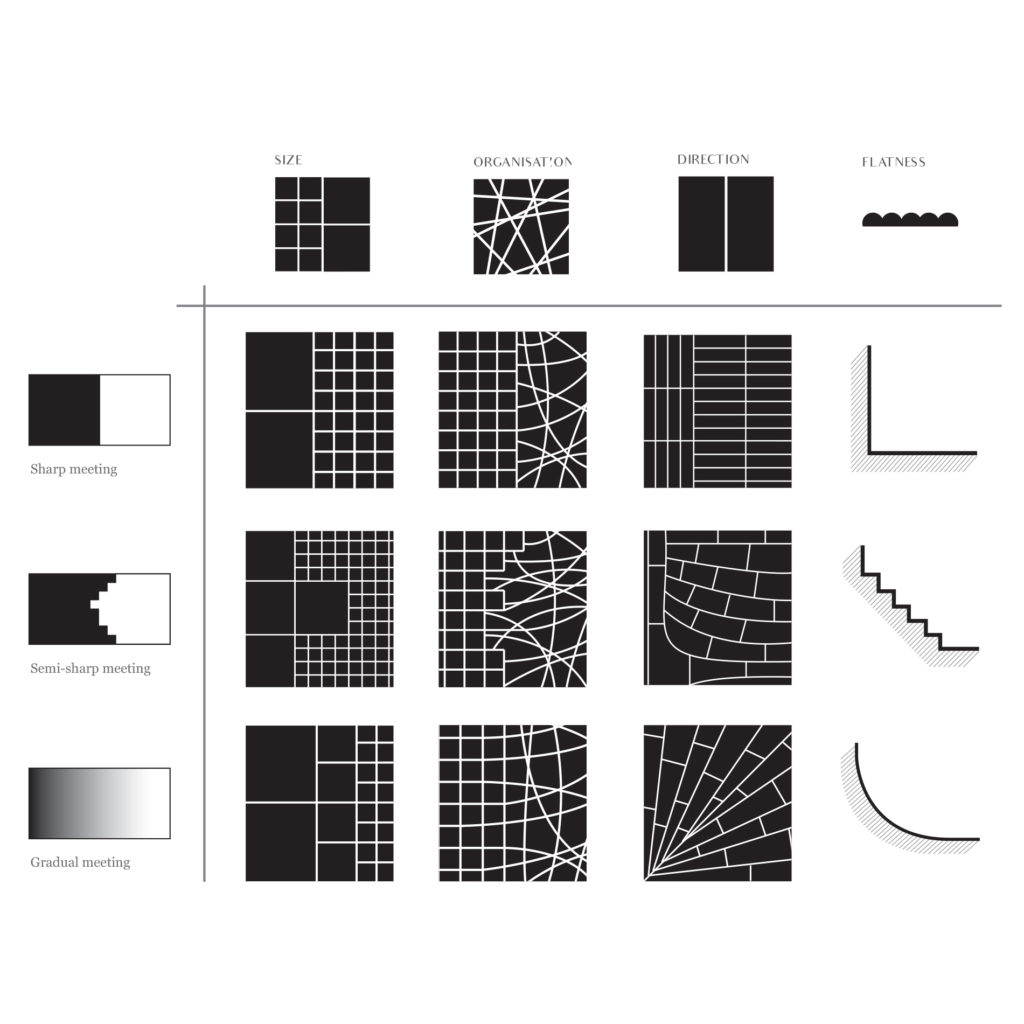

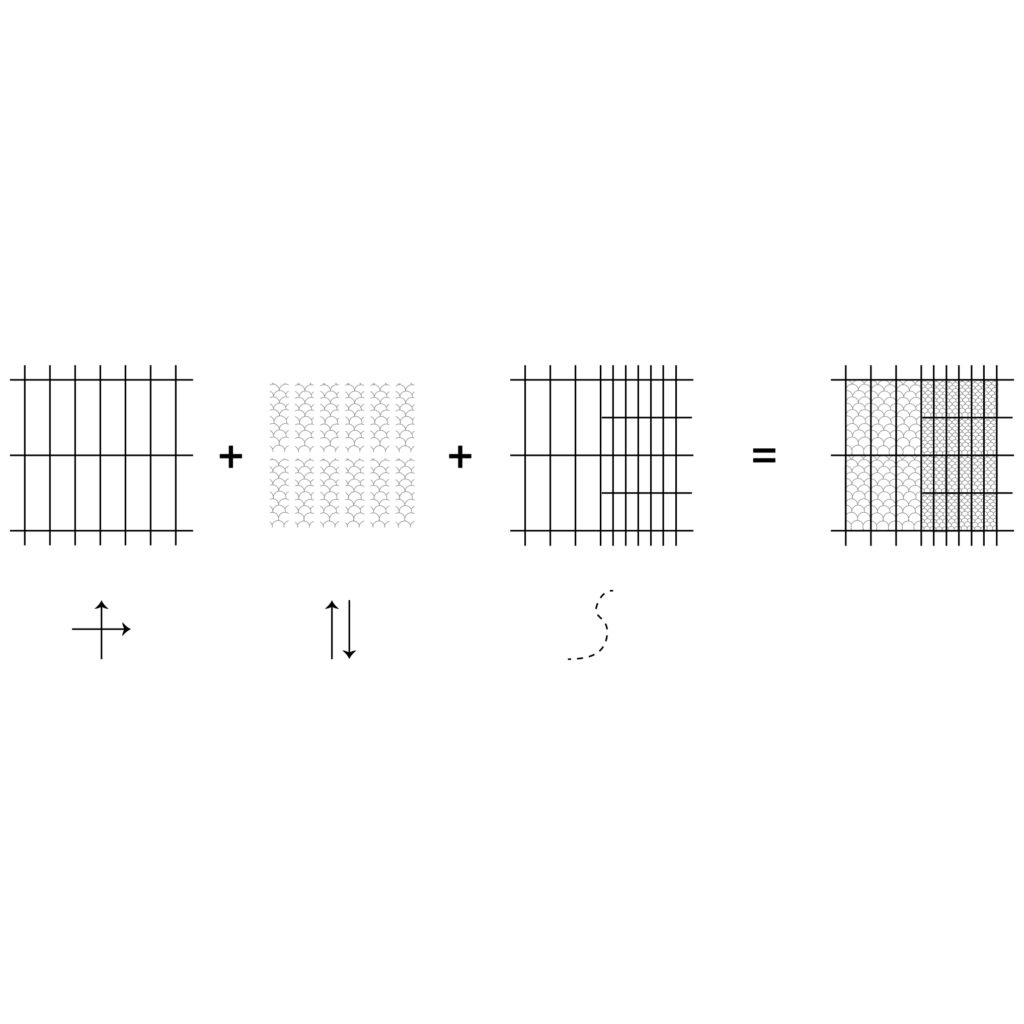

INVESTIGATION 4 – PATTERN MEETINGS

This investigation was done by sketching different pattern meetings through the parameters found for floor patterns in design investigation 1. The aim was to find different types of meetings between patterns and analyse how they could be beneficial in the bath house.

RESULT

Three types of meetings were found and studied for the different pattern qualities: the sharp meeting, the semi-sharp meeting and the gradual meeting. These meetings have different properties, making them useful for different functions in the bath house. For instance, the sharp meeting can be useful when wanting to create a stark difference, such as informing the visitor if they are on the tactile path or not, while the gradual pattern could be of interest in meetings concerning body parts, such as if a pool floor morphs into seating.

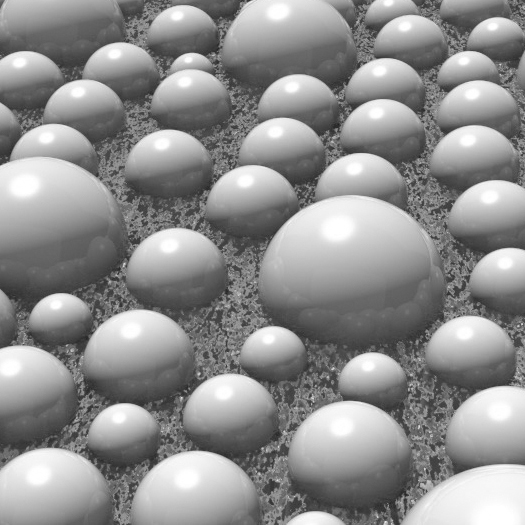

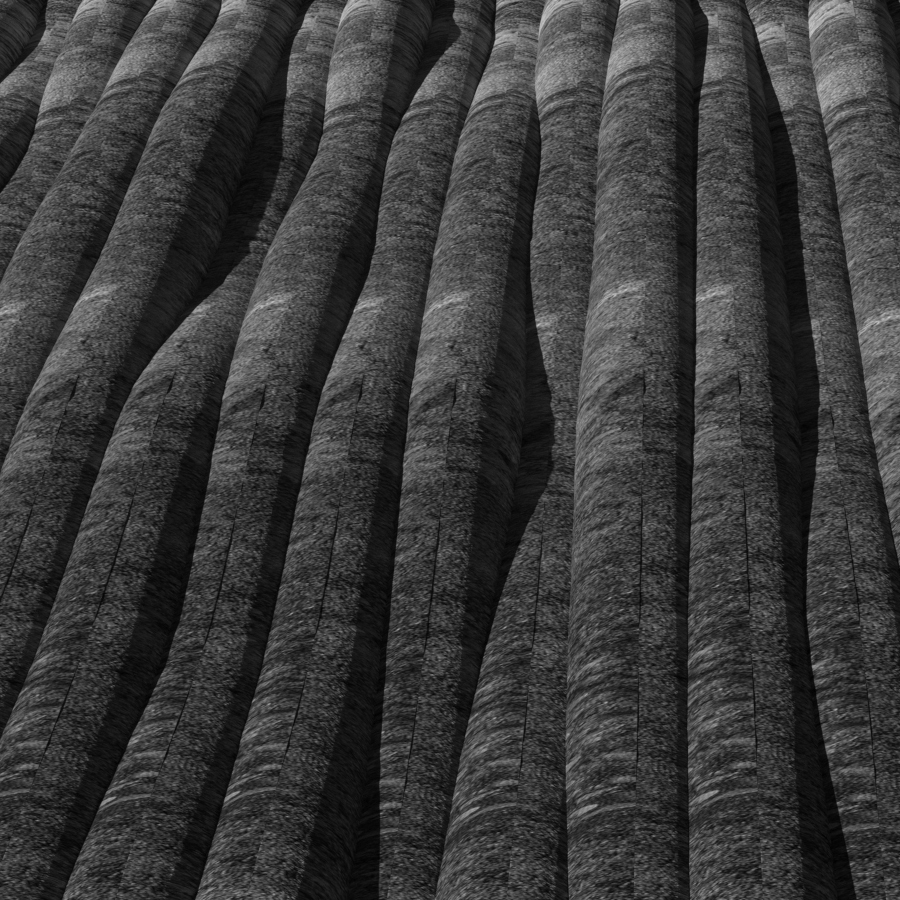

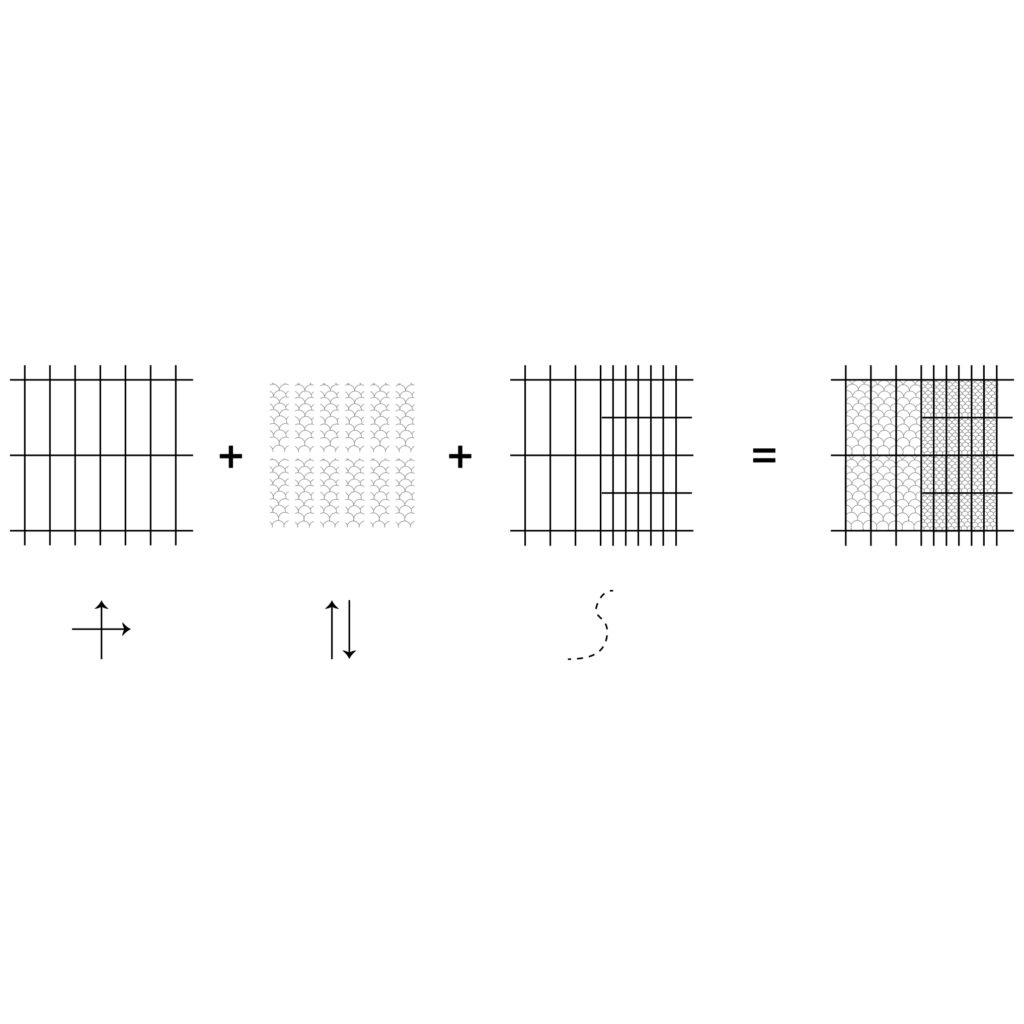

INVESTIGATION 5 – FOREST PATTERNS

The method of this investigation was to document and analyse common forest patterns in order to find patterns that could be used in the bathhouse and to look into pattern strategies overall.

RESULT

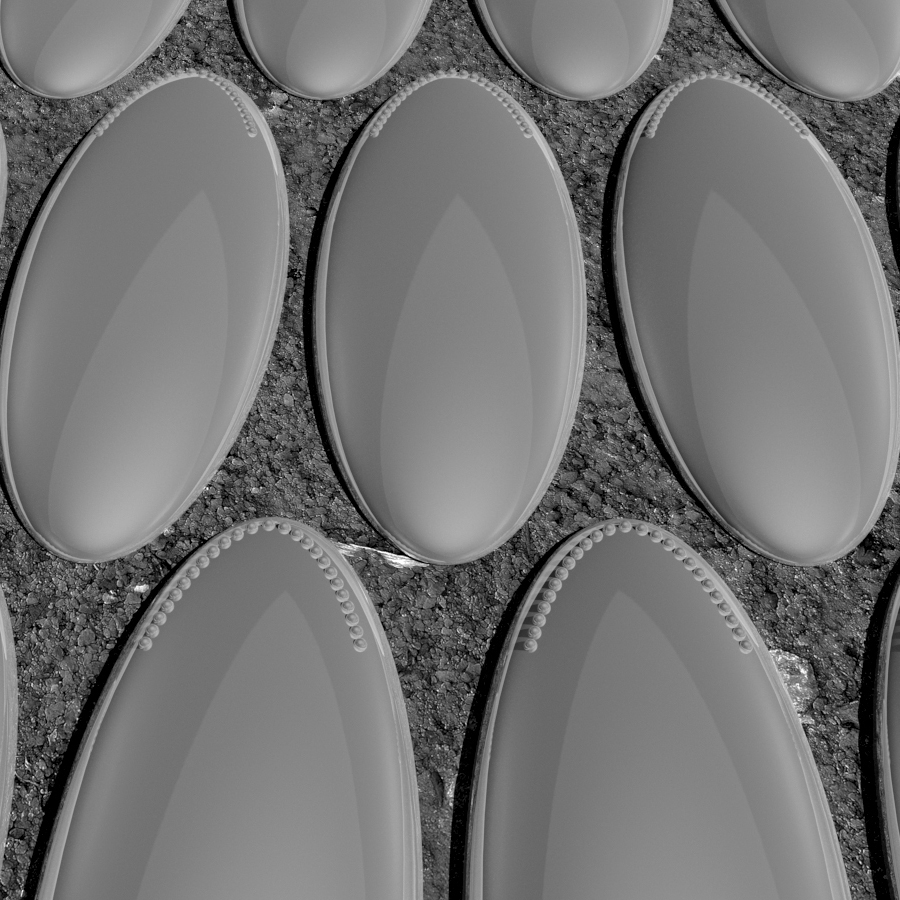

Aside from finding several patterns that could be used for the building, the experiment also revealed certain overall parameters about pattern logic in general. One such major insight was that frequently, in nature, inner patterns existed within outer patterns. One such example is how the fir cone has an overlapping, radial pattern of flakes, and then on each flake it has an inner linear pattern. This way of having a multi-layered system of patterns could be used in the tiles for the tactile paths in order to give a multitude of information within one system, which is shown in the diagram. An outer pattern makes it possible to distinguish between the x- and y-direction of a room. An inner pattern allows for knowledge of whether one is moving forwards or backwards. A disfigurement of the pattern, such as change in size or z-direction, makes it possible to know whether one is on the tactile path or not.

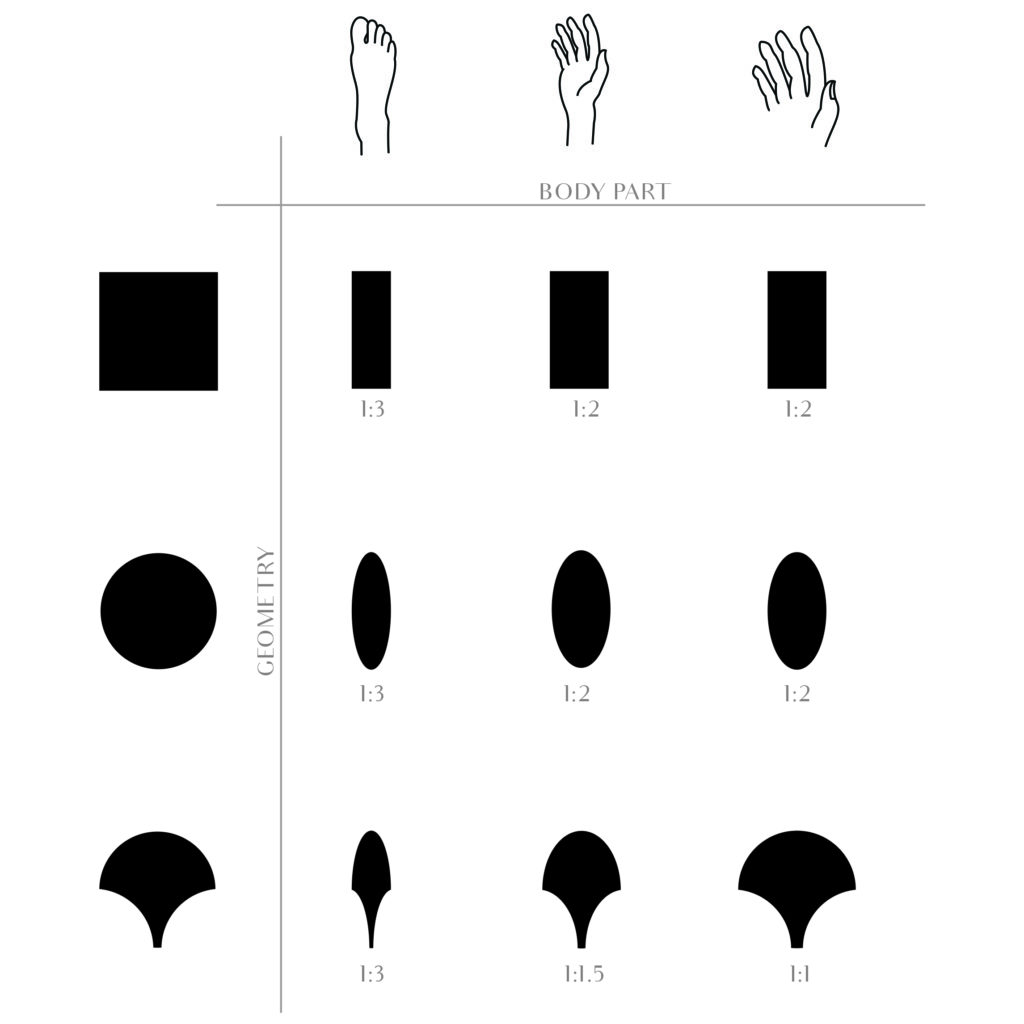

INVESTIGATION 6 – TILE RATIOS

By creating prototypes of common tile patterns with different ratios between height and width, and testing them on different body parts, it was possible to determine which ratios made it possible to sense a direction in the tile.

RESULT

Feet needed the most difference between length and width in order to sense a direction. Hands and fingers generally could sense a direction with similar measurements. The geometry which was not symmetrical in two directions was easier for the hand and finger to sense a direction in, without having that much difference in the ratio. However, this shape was difficult to understand by foot.

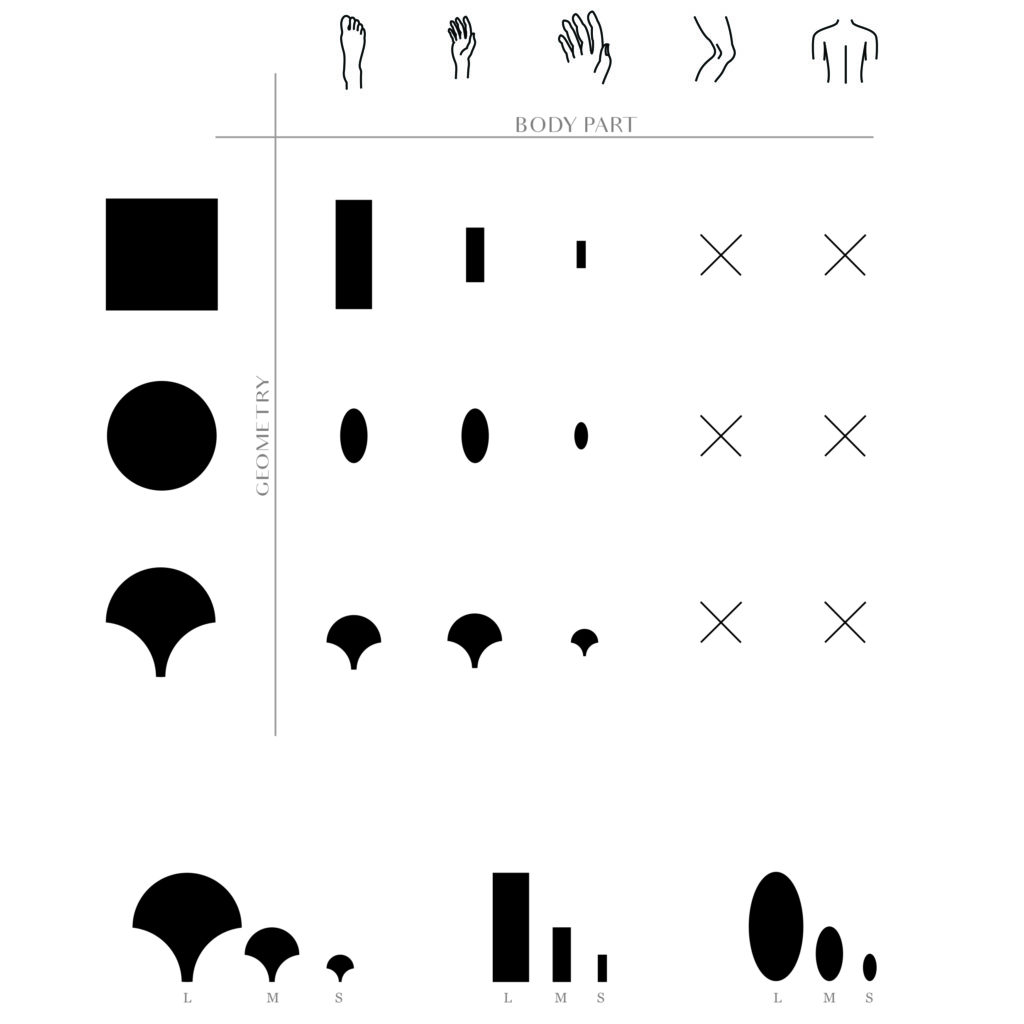

INVESTIGATION 7 – TILE SIZE

In this investigation, the prototypes found in investigation 6 were made with different sizes and then tested on different body parts in order to find how the size of a tile is experienced for different parts of the body.

RESULT

In general, the medium size was the most appropriate for both hands and feet, while fingers were capable of distinguishing even the smallest pattern. For feet the size of the tile was not as relevant as the ratio between grout and tile. If the grout was too small, it was impossible to sense the pattern by foot. The patterns were impossible to determine for back and leg.

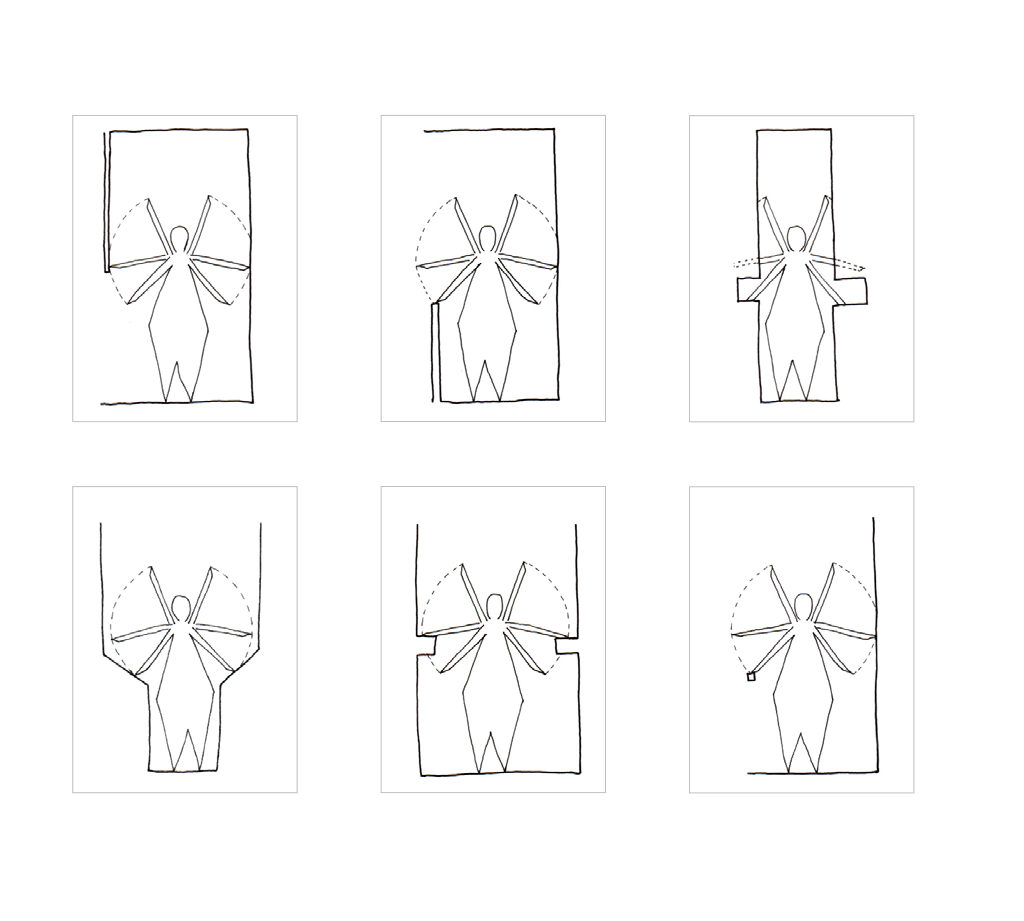

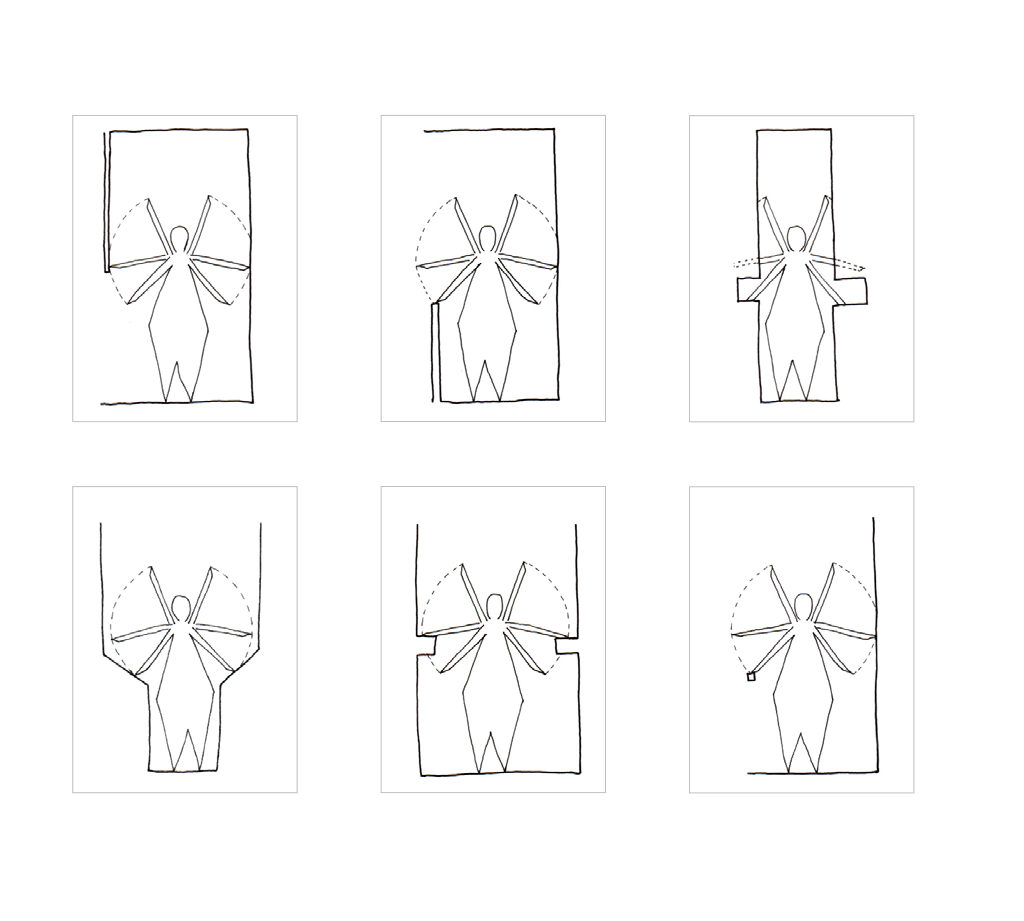

INVESTIGATION 8 – ORGANISATION

This investigate looked at how the shape of the building affects the organisation of spaces by sketching different floor plan options. The investigations looked at floor plans with a rectangular, square, circular and oval courtyard.

RESULT

The circular courtyard gives the optimal floor plan in regards to circulation and of these the plan in row two, column one, is best suited for the theme of the four seasons. This plan would yield two longer spaces with a clear direction for spring and autumn, while winter and summer will lack direction and are given good proportions.

INVESTIGATION 9 – TOUCHING SPACE

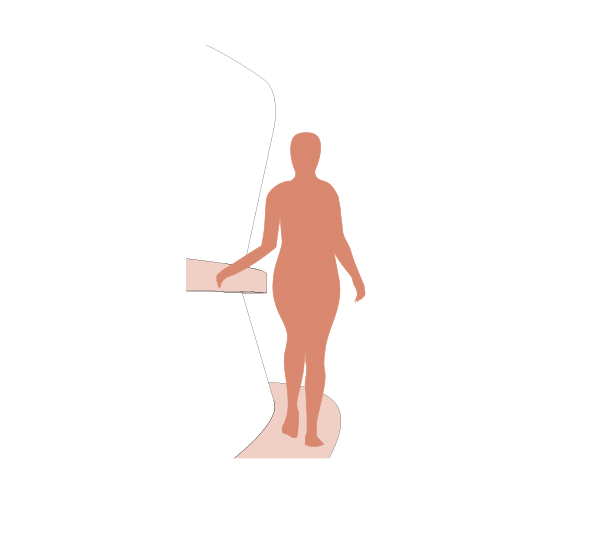

This investigation looked into how the body interacts with space in order to see how space is affected by creating a design focused on tactility.

RESULT

Through the sketches it became apparent that there are four different levels of touch between body and space, ranging from only having one connection to having four connections with space. If there is only one connection this will, almost always, be between feet and floor. If there are several connections, they can be created in a multitude of ways. Some of the section sketches can be seen to the left.

The following design strategies can be implemented in other projects in order to receive a more multi-sensory architecture. The strategies mainly increase the sense of touch in a project, but some can be applied to other senses as well.

EXCLUDE VISION

In order to refrain from getting seduced by mesmerising visuals it is important to let go of visual design at the initial design stage. Even while designing a space covered in darkness it was difficult to not consider how the design would look like and this habit of letting the eye decide is quite rooted in our decision making. Therefore, regardless of which of the non-visual senses one wants to incorporate, it is important to consider them while excluding the visual experience. How should it feel to touch this space? What does it sound like? What scents linger here?

FOCUS ON HANDS

In most public buildings, our hands are our main tactile connection to architecture. Shoes prevent a close connection to the floor, but hands are at most times, free to explore. Therefore, in order to design for touch, focus on design for hands. Door handles, railings and walls create great opportunities to explore tactile design.

HAND TRAILS, NOT JUST FOOT TRAILS

The freedom of the hand can further be utilised in tactile trails. Today, tactile trails are designed for the feet, but when possible, creating a complement for the hand would be useful. More information can be interpreted through fingers than is possible through feet, especially while wearing shoes, and it also creates the possibility of incorporating information through braille.

COMMUNICATION THROUGH TOUCH

Information received through tactile trails tends to only give information regarding whether one is on or off the path. By rethinking the design of the trail pattern it is possible to give additional information such as in which direction the person is moving, whether you are moving towards or away from something as well as which type of activity the trail leads to.

BODY AND SPACE

Something that becomes more evident when designing for touch is the relationship between body and space. The reach of the body determines the touchable boundary of the space and this should be considered when designing for a haptic experience. By considering how body and space interacts it is possible to direct the tactile experience of the building, controlling which parts of the architecture that are within reach and which are not.

BODY AS A PARAMETER

The resolution of the nervous system varies over the body, which is important to consider when designing for a haptic experience. To design a tactile pattern for the fingers is wildly different than designing one for the back. It is important to consider how the body will interact with the area and, in consequence, how this affects parameters such as size, roughness and sharpness of the tactile pattern.

CONTRASTS

It is important to consider contrasts when designing a tactile experience. A smooth material, in close proximity to a rougher texture, creates an interesting dynamic. A warm material combined with a cold material enhances both experiences. This use of contrasts should not be solely used for tactile design, but can be applied to all senses and, thus, help create diverse and interesting spaces.

Blind Trust has been a project investigating the possibilities within non-visual design. The aim of the project is not to exclude visual design from architecture, but to critique the current domination vision has in architectural design. Ideally, ideas from this thesis can be used in combination with visual design, giving a holistic architectural experiences where all senses are meticulously considered in the design process.