A platform for the housing discourses

All things considered, it is not surprising that the debate on housing is both polarised and fragmented. The question hits home – literally – for everyone. Depending on ones’ point of view the problem is formulated differently, which leads to different ideas of the best way forward. It is perhaps most fair not to talk about the debate on housing as one, but a multitude of different divergences.

In terms of housing production, necessary levels have not been met during the last two or three decades. The deficit is most apparent in the metropolitan regions. Even though the need for rental dwellings is most pressing the stock has barely increased, partly due to transformations exceeding production. Political efforts of lowering housing standards for small apartments have been made in hopes of stimulating production of affordable housing. Even if successful, this permanently adds increased overcrowding for vulnerable groups, while also risking to amplify patterns of segregation.

Housing inequality has been shown to reproduce other inequalities in terms of financial resources, existential matters and health and well-being. Traffic separated planning, tenancy-based subsidies and social inequalities have conspired to enforce tenure segmentation and social divides. This friction intensifies exponentially when the housing patterns themselves widens the gap between different neighbourhoods and between homeowners and rental tenants.

The housing issue is pressing in a number of ways, not least due to its role in enhancing social and economic inequalities. What has happened in the Swedish housing market is in effect that you need to be affluent to get access to affordable housing. Increasingly large parts of the population struggle to find appropriate housing, which can be assumed to affect their sense of safety and stability. At the same time those who acquired a home before the age of the booming housing market can consider themselves winners as their homes continue to gain in value.

To Facilitate an Informed Societal Debate

We all have personal perceptions on housing, shaped by experience and ideology. In order to facilitate an informed and constructive debate that everyone feels confident to take part in there needs to be common points of departure; things that can spark an interest and make people feel strengthened to speak their mind. One way of achieving this is to visually situate the issue at venues of everyday life, like commuting hubs or shopping malls. By curating an exhibition that could be displayed at different places we can establish a common ground on which a fair debate can take place.

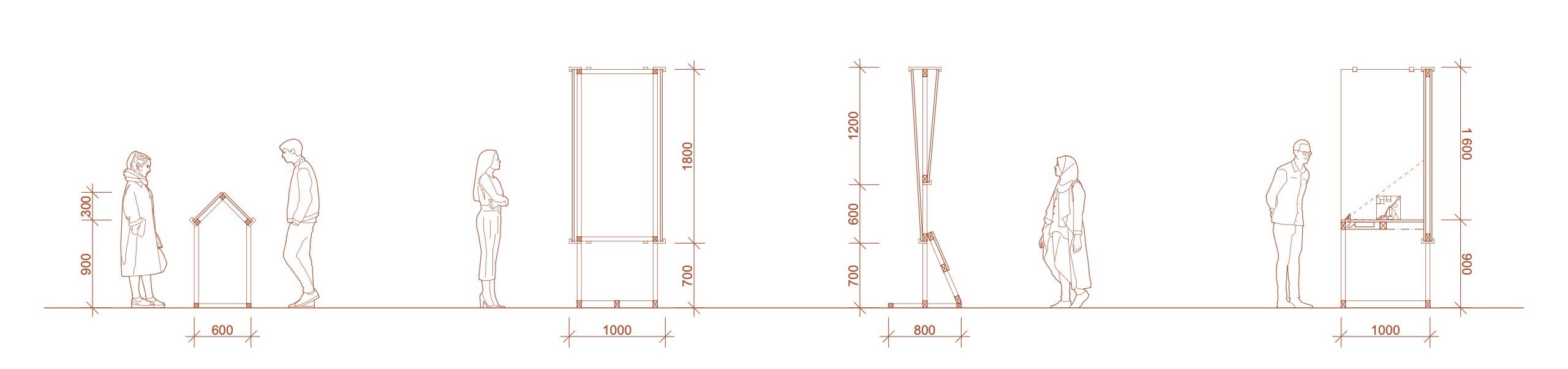

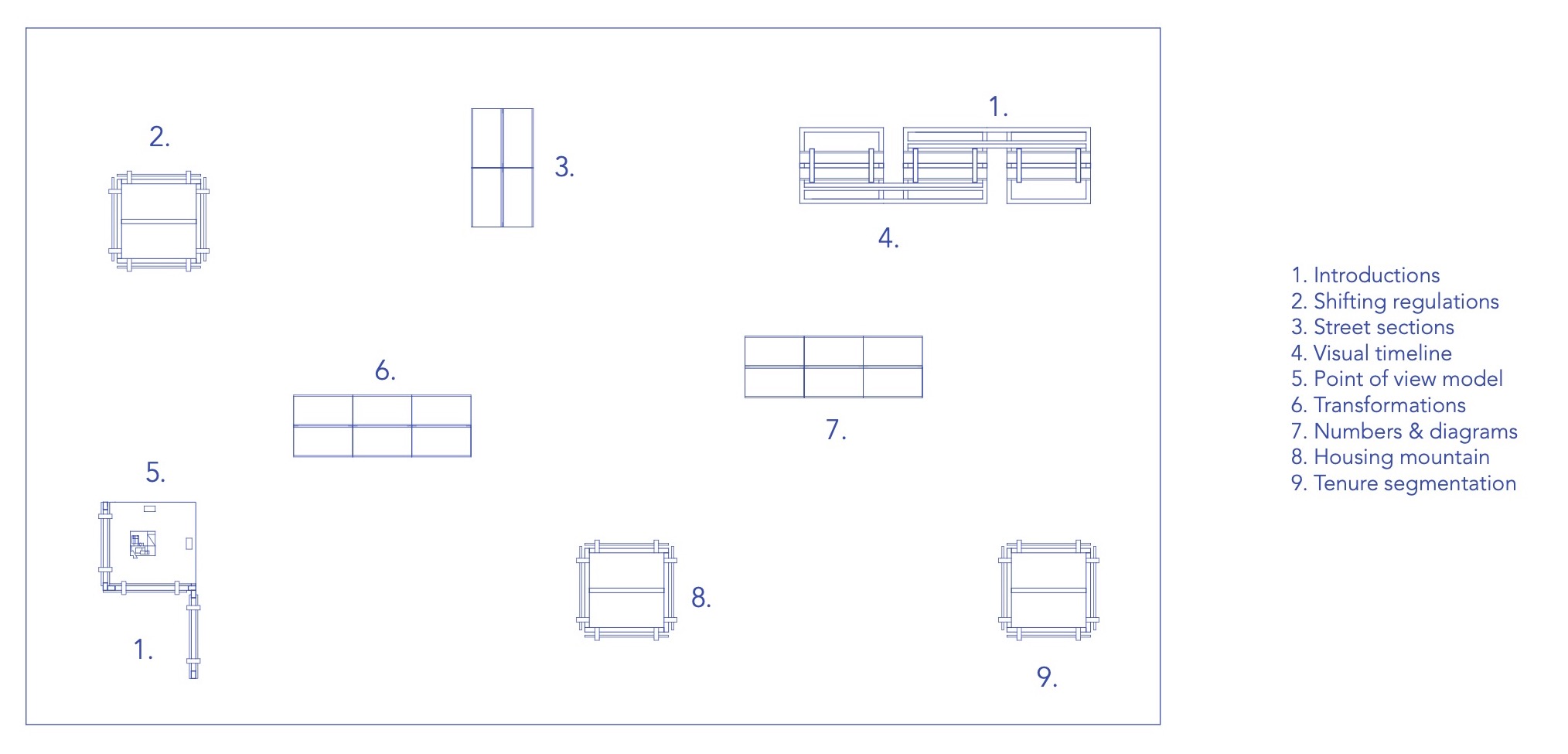

The exhibition was designed as an abstraction of a cityscape, reminding the visitor of walking around among different types of buildings. The fact that different housing typologies were represented was regarded of importance in order not to reinforce the private house as the sole metaphor for a home. Colour and design was used in order to draw interest.

The exhibition is meant to be able to be displayed at different places and can be adapted to the conditions of the site. At smaller venues a few selected parts could be displayed. There are no back sides, since the exhibition should be able to be free-standing.

While the goal is to reach a wide target group, the exhibition could also be displayed as a discussion material at specific events regarding housing and/or politics, like housing expos, Almedalen Week or Järva Week. By creating a sense of understanding through visual representations more people can join the discussion about what our housing system should do for us and how we can get there.

Conclusion

This thesis set out to identify and visualise factors of inequality on the Swedish housing market and how these have been tackled historically. It has shown that our point of view determines what we build. Adequate housing was a priority for the government from the 1930s and onwards and construction loans and municipal housing companies were important tools used to combat housing inequality. A universal housing approach which did not target specific vulnerable groups was implemented in order to avoid stigmatisation. The government took active measures to secure housing equality up until the 1970s, after which the responsibility gradually was transferred to market forces. Homeowners were now allowed to deduct interest costs from their income taxation, which made private housing more favourable than rental housing. A process of residualisation amplified patterns of segregation. From the 1990s and onwards the municipal housing companies had lost their favourable state support and had to compete on the same terms as private landlords. This was further reinforced by an adaptation to EU rules on competition in 2011. While the housing costs continued to rise the government further confided in market forces to solve the shortage of affordable housing. Presumption rents, and later inquiries on unrestrained rent-setting and lower amortisation requirements, continued the change from state action to market incentives.

What we build today is not reflecting what we need. The level of construction is not sufficient to provide housing for the growing population, while rental housing accounts for a decreasing share of all dwellings. Deviations from the regulations meant to secure a good housing standard are hoped to incentivise production of affordable dwellings but risk leading to increased stigmatisation and segregation. The factors of inequality highlighted in this paper shows that housing has a clear effect on social and economic inequality – and vice versa. Who we are determines how we reside, as there is a clear correlation between housing and background, income and geographical area. On the other hand, our way of residing also determines who we become, as it affects our identity and perception of self, while enhancing wealth gaps and carries them across generations.

Conveying a message visually comes with a lot of trade-offs. There is a limit to how much information that can be portrayed before the recipient feels hesitant to immerse in the visuals. In order to make some points clear enough, others have to go. During the process of this thesis project the visuals have changed from being strictly graphical and complex into more accessible illustrations. The aim was to explain and spark discussion, which is probably easier achieved by making clear statements and pose open questions.

This thesis may well have asked more questions than it has provided answers – questions that will not be answered by data or research. Answers to how the Swedish housing regime should evolve must spring from democratic processes, which cannot function without a common base of understanding. Knowledge is a prerequisite for true democratic decisions. This thesis hopefully helped ever so slightly in widening the understanding of housing equality, if at least for the author herself.