How can the understanding of the pedestrian movements in our cities support the design of architecture and public space in the strive for cities made for people?

How do we design architecture and public space that is shaped by the pedestrian movements in our cities rather than the other way around?

Can pedestrian movements shape architecture and public space?

55% of the world’s population live in urban areas today. By 2050, that number is expected to be 68%. The terms and conditions of our cities are rapidly changing, and more and more people inhabit streets and public spaces. At the same time, the more cars continue to fill up our streets, the more focused our politicians and traffic planners have become on making room for even more cars. There is a global will to become more sustainable and fossil free, but a reluctance to leave the car and the infrastructure that comes with it behind.

The consensus is that we need to build for pedestrians, but often the actions taken to improve pedestrian life lack the deep understanding of their behaviors. There is a disconnect between the knowledge that we possess through research and the professions that are trying to make reality of it. The purpose of this master’s thesis is to support architects and planners in making the right choices; to help them understand the complexities of pedestrians in our cities and how to proactively design for them. By generating a set of design factors, based on existing research and knowledge, to assess the degree of pedestrian presence and quality of experience that a design provides or will provide, the aim is to enhance the practical skills of architects and planners in all stages of urban planning, further bridging the gap between research and practice.

The chosen method for this master’s thesis is mainly research for design. The research and knowledge is drawn from three specific fields of study connected to urban design, focusing on public spaces, and urban studies, focusing on the relation between urban design and pedestrian movement:

Public life studies, mostly represented by the direct observation works of Jan Gehl and his colleagues, but also other pioneers of the field,

Space syntax studies, mostly represented by the empirically tested modeling and analyses of public space configurations in relation to pedestrian movement by Bill Hillier and his colleagues, and

Built environment studies, mostly represented by different existing guidelines promoting pedestrian movement, based on empirical studies and statistical modeling.

The final result is mainly a design toolbox consisting of 20 design factors, divided into categories, and a workflow on how to use the design toolbox in a design process. A design proposal has also been developed to put the theory part of the master’s thesis to test, attempting to apply the design toolbox as well as re-developing and improving it during the process.

The 20 design factors

When working with public space and pedestrians, it becomes natural to divide the design factors into two different scales: the macro scale and the micro scale.

The macro scale focuses on the larger context and network; the individual site as a part of a whole. It is important to understand that decisions made in city and regional planning, in site planning and at the small scale are very closely linked to each other. If good conditions are not created through decisions at the primary planning levels, good conditions rarely exist for working at the small scale either.

The micro scale focuses on the immediate environment that the individual person or pedestrian meets and uses every day. It is at the micro scale that we evaluate and experience all planning decisions made.

The 20 design factors are also divided into two different categories; principle factors and provision factors. The principle factors are more general and discuss properties that involve the design or project as a whole. The provision factors work on a more detailed level, discussing the providing or supplying of specific elements.

the design toolbox

The design toolbox does not only consist of the 20 design factors on how to support pedestrian movement with design and the connected check-up questions. It presents a workflow, a recommended process, on how to use different methods and analyses together with the design factors. The workflow chart illustrates the recommended process, divided into 5 steps.

The 20 design factors of the design toolbox have been developed to be as literal and measurable as possible, so that they are as easy as possible to use. A lot of aspects will not be mentioned in the factors because they can not be literally and separately assessed, they are believed to be a direct net effect of the other factors. For example, adaptation, safety, comfort, attractiveness and liveability are features that will naturally be the indirect result of a design that is focusing on being pedestrian-friendly by considering the 20 design factors.

This means that whereas the design toolbox is focusing on literal design factors connected to improving pedestrian experiences, the design result may very well be a public space that is generally appreciated in several aspects beyond the aspect of the specific pedestrian experience.

the design proposal

Is the design toolbox and its proposed workflow useful and applicable? Is it helpful in the strive for a new and better pedestrian usage of the chosen project site?

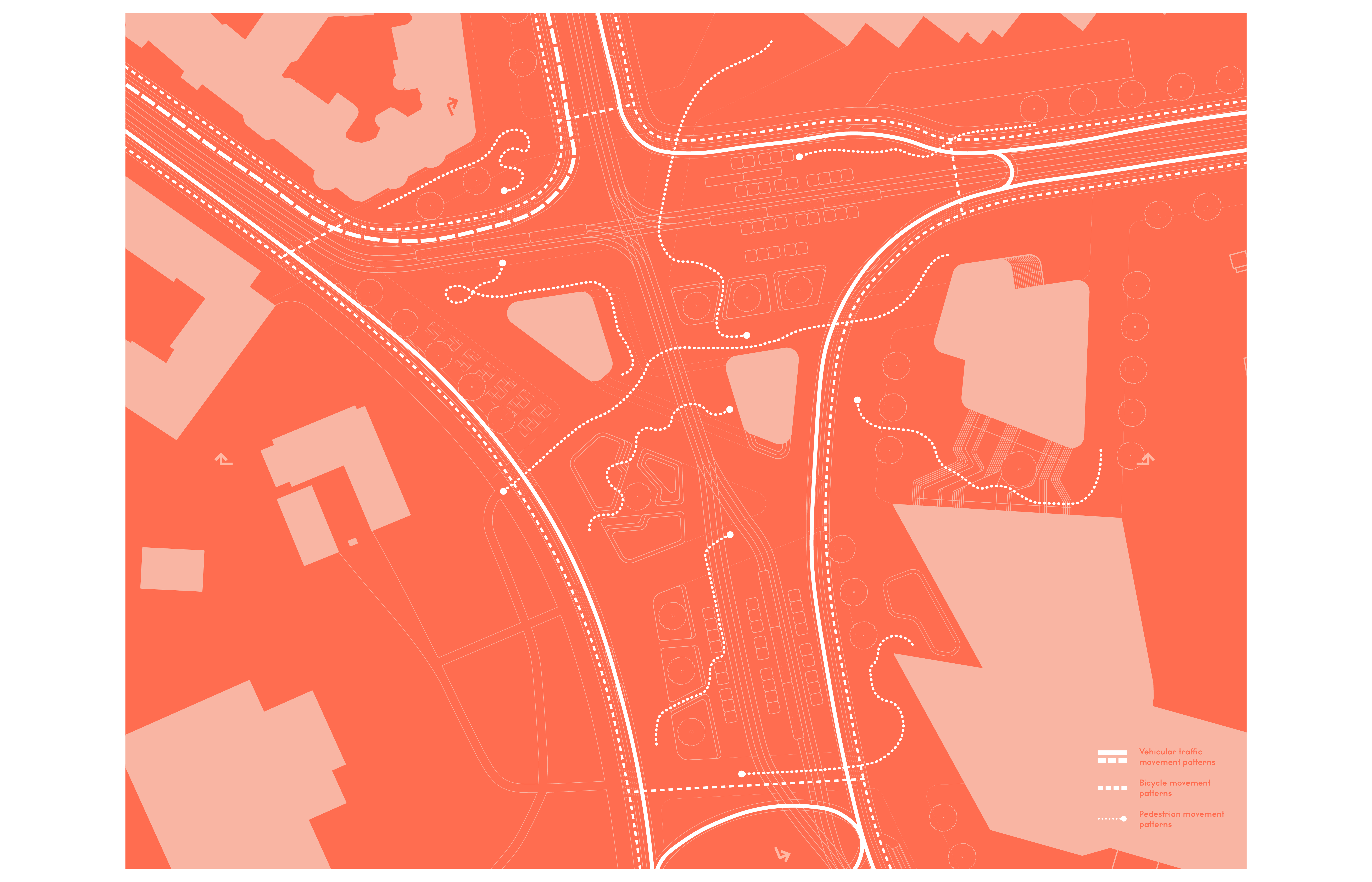

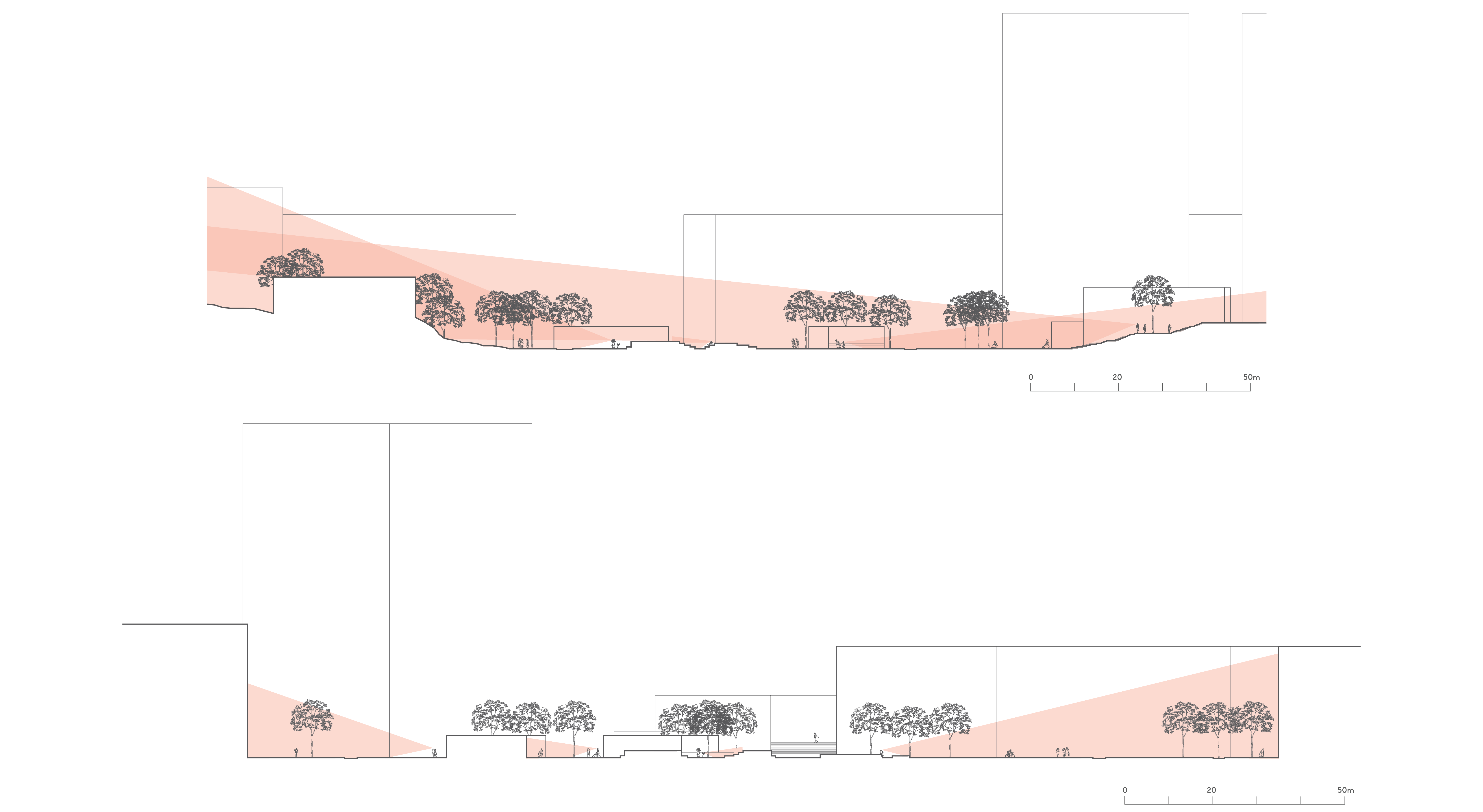

The project site of Korsvägen was chosen based on it being a public space handling a lot of pedestrian movements at the same time as offering room to design. It was also chosen based on its relevance due to its ongoing and future development plans.

The main aim of the design proposal was to test and apply the design toolbox, both in the analysing and evaluating phase and in the design process phase. These sections of the master’s thesis can be found in the booklet, in chapter 5: design proposal.

did i succeed? what did i find out?

The main focus of this master’s thesis has been to test if public space can be designed derived from the understanding of pedestrian movement and how this can be done with the use of design factors that have been distilled based on research. The question has always been; how can this knowledge based on research be translated into practical work? The approach has been to look at design of public space from another perspective, to have another starting point to design than what might be the usual. In addition to this, to find out if good design can follow from this approach.

Referring back to the research questions, whether public space can be designed derived from the understanding of pedestrian movement and if this understanding would support the design of architecture and public space in the strive for cities made for people, the findings from this master’s thesis would suggest that the answer is positive. The design proposal executed in this master’s thesis is only one of many possible applications and the idea of a public space being designed from this approach can be scaled and applied into any other context.

How can the understanding of the pedestrian movements in our cities support the design of architecture and public space in the strive for cities made for people?

How do we design architecture and public space that is shaped by the pedestrian movements in our cities rather than the other way around?

Can pedestrian movements shape architecture and public space?