not just sorry but thanks.

‘Not just sorry, but thanks’ finds its genesis in Bruce Pascoe’s work Dark Emu where he writes: “It seems improbable that a country can continue to hide from the actuality of its history in order to validate the fact that having said sorry, we refuse to say thanks” (2014:228) and is an acknowledgment of the failure of architectural practice and education to face its role in the continuation of colonialism in Australia.

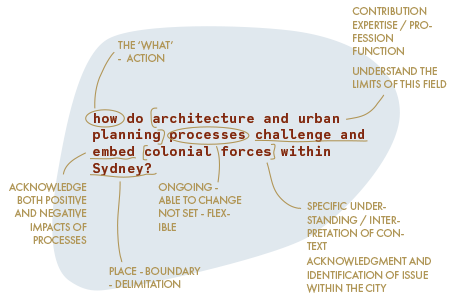

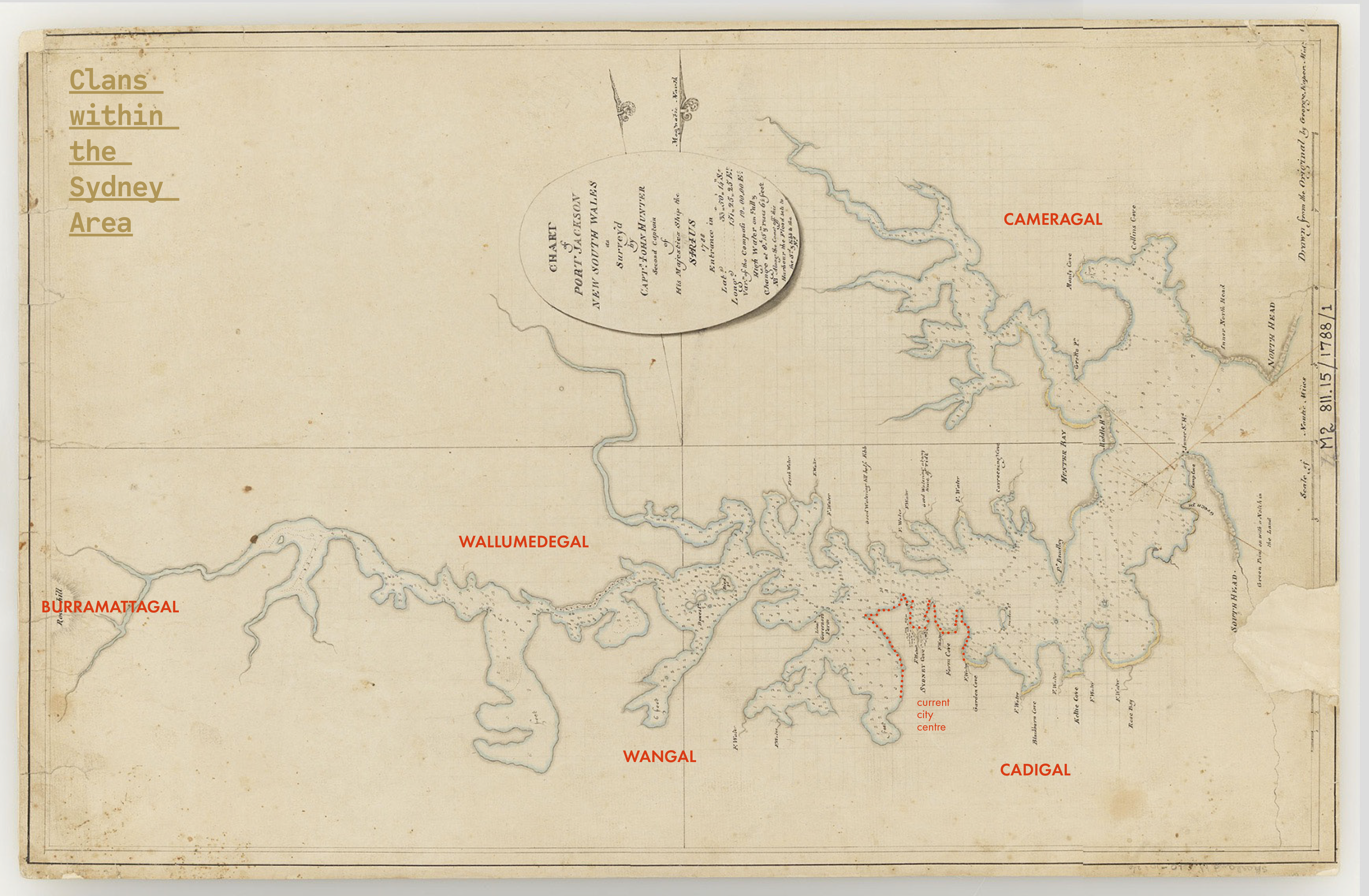

This work focuses on identifying how architecture and urban planning processes challenge or embed colonial forces within the city of Sydney. Australia’s settler colonialism is identified as ongoing, and manifested through physical and structural ways. This thesis explores this manifestation in three areas: architectural policy and accreditation; architectural education; and architectural practice on an urban and public scale.

Processes that embed settler colonialism can be identified by their silence and omission; as such, they represent a ‘business-as-usual’ response. Settler colonialism relies on silence and omission to remain invisible, wherein it holds its power. Thus, policy, education and practices that do not actively acknowledge colonialism and its damage to the First Peoples of Australia can be classified as ‘embedding’.

Processes that challenge settler colonialism can be identified by their engagement with First Peoples’ communities and culture. Theses are policies, educational programmes and architectural practices led by First Peoples and/or those which highlight and celebrate First Peoples’ knowledge, voices and cultures.

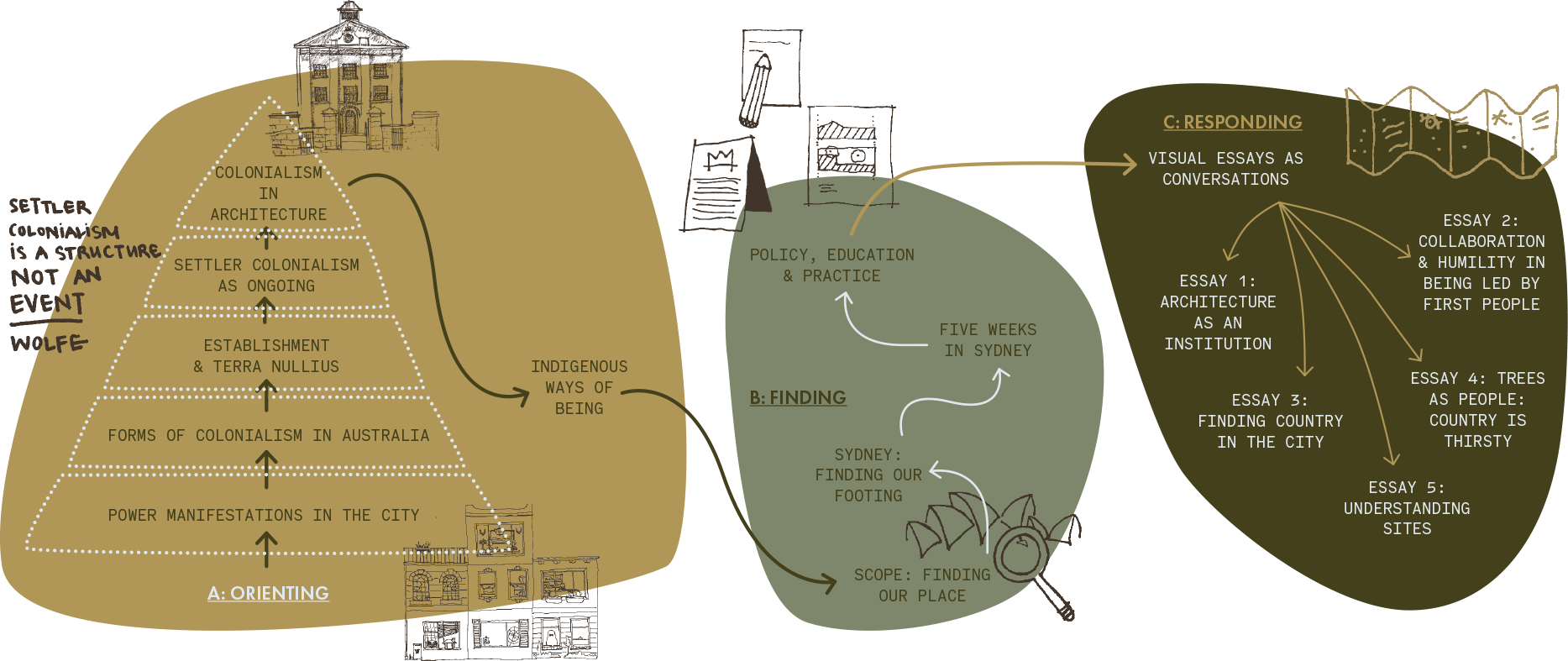

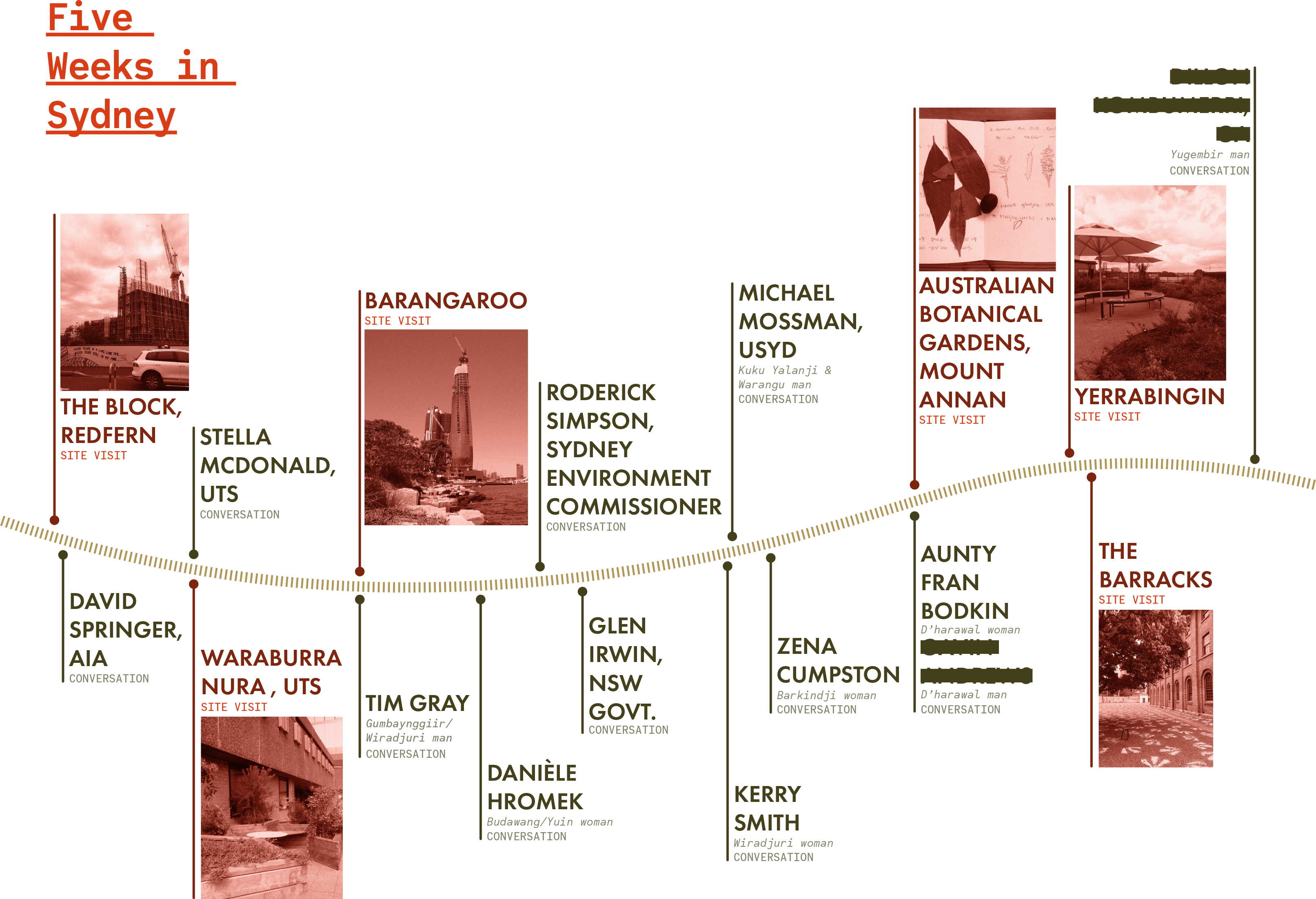

This thesis consists of synthesised theoretical writings, interviews and conversations, data collection, and cartographic exercises. The outcomes of this thesis are contained in three chapters exploring existence and evolution of settler colonialism in Australia and the built environment, the specific manifestations in Sydney, and finally, a series of visual essays performed as conversations to provoke discussions about the role of the architect and the ways in which settler colonialism can be unsettled. Participatory processes and co-design methodologies are employed to ensure the outcome evolves from an ongoing conversation with First Peoples.

“It seems improbable that a country can continue to hide from the actuality of its history in order to validate the fact that having said sorry, we refuse to say thanks.”

BRUCE PASCOE, ‘DARK EMU’, p. 228

The work is divided into three chapters: Orienting, Finding, and Responding. In ‘Orienting’, the Australian context is established; this encompasses the contemporary colonial and Indigenous frameworks as I understand them and as they are relevant to this thesis. The fieldwork collecting during a five week study trip in Sydney will be exhibited in ‘Finding’; however the primary contribution is demonstrated in ‘Responding’. In this chapter, the material from ‘Finding’ is digested, explored, teased out and synthesised in a series of five visual essays performed as conversations with notes for future practice.

a | orienting

“One of the notable characteristics of settler colonial states is the refusal to recognise themselves as such, requiring a continual disavowal of history, Indigenous peoples’ resistance to settlement, Indigenous peoples’ claims to stolen land, and how settler colonialism is indeed ongoing, not an event contained in the past. Settler colonialism is made invisible within settler societies and uses institutional apparatuses to ‘cover its tracks’.”

McCOY, TUCK & McKENZIE, ‘LAND EDUCATION’, P.7

Eve Tuck is Unangax and an enrolled member of the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island in Alaska

Read the essays in the booklet:

- power and colonialism

- 1788

- in architecture

“Country is the keeper of the knowledge we share with you…It guides us and teaches us. Country has awareness, it is not just a backdrop. It knows and is part of us. Country is our homeland. It is home and land, but it is more than that. It is the seas and the waters, the rocks and the soils, the animals and the winds and people too…Country is the way humans and non-humans co-become, the way we emerge together, have always emerged together and will always emerge together.”

GAY’WU GROUP OF WOMEN, ‘SONG SPIRALS’, 2019:XXI

The Gay’wu group of women speak collectively from Rorruwuy, Dätuwuy land and Bawaka, Gumatj land on Yolŋu Country

While the variety and diversity of First Peoples is to be recognised, there are shared cultural tenets. Some key concepts are shared for the reader to familiarise themselves with the Australian context. This is by no means exhaustive, and is intended as a simple guide.

As the author of this work, I did not feel it was my place to try and describe these concepts or ways of being in my own words. There are extensive writings from First Nations Peoples regarding their family or tribal ways of being, and their words are far more necessary to hear here.

For more, read ‘Chapter A: Orienting’ in the booklet

b | finding

A five week study trip in Sydney was designed to both navigate and explore the structural and social elements. Engaging with the institutions that guided the architectural community through policy, archive studies, surveys, and document studies was complemented by more human interactions: talking (interviewing) with people, walking (both with others, and alone) and interrogating the situation of oneself as a researcher in place.

For more, read ‘Chapter B: Finding’ in the booklet

c | responding

‘Responding’ proposes a series of five visual essays which are performed as a way of challenging contemporary ways of practice, and provoking one to reconsider one’s own relationship with place, people and practice. The essays intersect with policy, practice and education continuing our exploration of their intertwined relationship. Whether working within colonial contexts or not, these essays touch the roles played by architects and advocate for a more engaged, and proactively kinder practice.

essay one: architecture as an institution

This essay explores the institutional structures which shape the architectural community in Sydney, and the structural ways it has failed Indigenous peoples and culture. We pose the question: what would it look like if First Peoples were able to guide our ways of being?

essay two: collaboration and humility in being led by First Peoples

While all collaborations have their difficulties, this essay explores the fraught cultural landscape of collaboration for First Peoples. How can non-Indigenous designers be more aware, more conscious and more caring in collaboration?

essay three: finding Country in the city

Here, we unpack what it means to connect to Country in Sydney. How can we (as both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples) connect to Country, and how can increasing information create space for cultural healing?

essay four: trees as people

In our age of climate change, have we lost the way we listen and treat our natural environments? How can seeing, listening and talking to trees like people shift the way we treat our natural environment and celebrate Indigenous knowledges?

essay five: understanding site

As architects we are expected to engage with our sites in a way that assumes we have knowledge of how they are composed. In this essay, we question where that knowledge comes from, and which voices are not being heard.

not just sorry but thanks.

Having never apologised to a First Nations person, I would like to take a moment to consider the place of an apology in this context. Apologies do not sit comfortably with me yet, and this is because apologising to First People sets up one of those strange dynamics that only whiteness seems to achieve. By saying sorry, we place a burden on Indigenous peoples to accept, or to forgive. The burden to forgive, in this context, undermines feelings of unresolved trauma, and is weakened when it is continual betrayal. While the choice to forgive or accept this apology is within the power of the Indigenous person/s, the implied burden and obligation sits uncomfortably with me; to say sorry for something requires the action of offense to stop. Colonialism in Australia has not stopped. It is ongoing and structurally embedded in all facets of our society. To apologise, and yet continue to inflict pain, is hypocrisy.

We saw this in reactions to Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generation in 2008. This apology, while overdue, did not end cultural and community-based fragmentation, nor did it see an improvement in conditions for Indigenous peoples in Australia. It was unsatisfying, and undermining.

Instead of saying sorry, I propose that now is the time for saying thank you. Thank you for 100,000 years of custodianship. Thank you for the knowledge you have of our lands. Thank you for sharing and teaching despite the damage you have suffered, and continue to suffer, under colonial dispossession.

The more we say thank you, the more we learn to value and acknowledge the First Peoples of this place, and work to build a society that is more respectful and able to celebrate those who we co-exist with. Only then can we turn and say sorry.

For this project, a huge thank you to everyone who talked, shared, walked and guided me. To those First Nations People, I cannot understate the generosity in your willingness to share with me, a stranger. As Michael said to me, “You really appeared out of the blue.”

Thank you to Jo, whose first email excited me, challenged me and gave me hope that this thesis was possible. To Kerry, thank you for sitting, sharing so honestly and for making me laugh! To Aunty Fran and [name redacted], thank you for making me feel so welcome and comfortable, and sharing your experiences and knowledge. To Michael and [name redacted], thank you for being slow with me and reminding me that this change doesn’t have to be so complicated if we take the time to listen and try. To Uncle Dennis, thank you for your candidness and your willingness to share, it was wonderful to hear your perspective. To Zena, I was struck by how honest you were despite not knowing me. Your frustrations reminded me how easy it is to be harmful, and motivated me to be proactive. Thank you for the time you spent, and for your words of guidance. Danièle, thank you for your writings – they frightened me, unsettled me, made me angry at the ways we are forced to move through the world, and demonstrated the beauty your practice embeds. Thank you for your continued correspondence, and words of motivation. Again, you gave so generously although we only met once.