Design and reflections

Throughout the research, I found the term community lacking as it only describes the main normative social formations. Its usage in architectural discourse has an inclusive meaning, but as my work with street writers progressed, I found it to be very exclusive. For inclusion and spatial justice, it is essential to not place normative restrictions to social behaviours through the use of language.

This separation is what I believe is at play when marketing sub-culture as an identity for gentrification. Proposing sub-cultures as an identity marker is problematic because of the connotation it has to commodification and objectification. The undetermined longevity of the proposed identity marker is seen as a threat to the subculture’s growth.

Agency

Ownership and authorship were major aspects of the ideas of commodification. The property owner owns the land and structure, but in terms of the vacant building, they do not have authorship over it. By that I mean, when adaptive re-use of the disused structures is promoted, sub-culture should be inviting the society, rather than allowing the sub-culture to stay. This mental shift in perception will become vital in the success of marketing sub-cultures as identifying markers of an area. It allows the social group to find their way back into society rather than being further alienated.

How do we approach design for inclusivity of sub-cultures in adaptive re-use scheme?

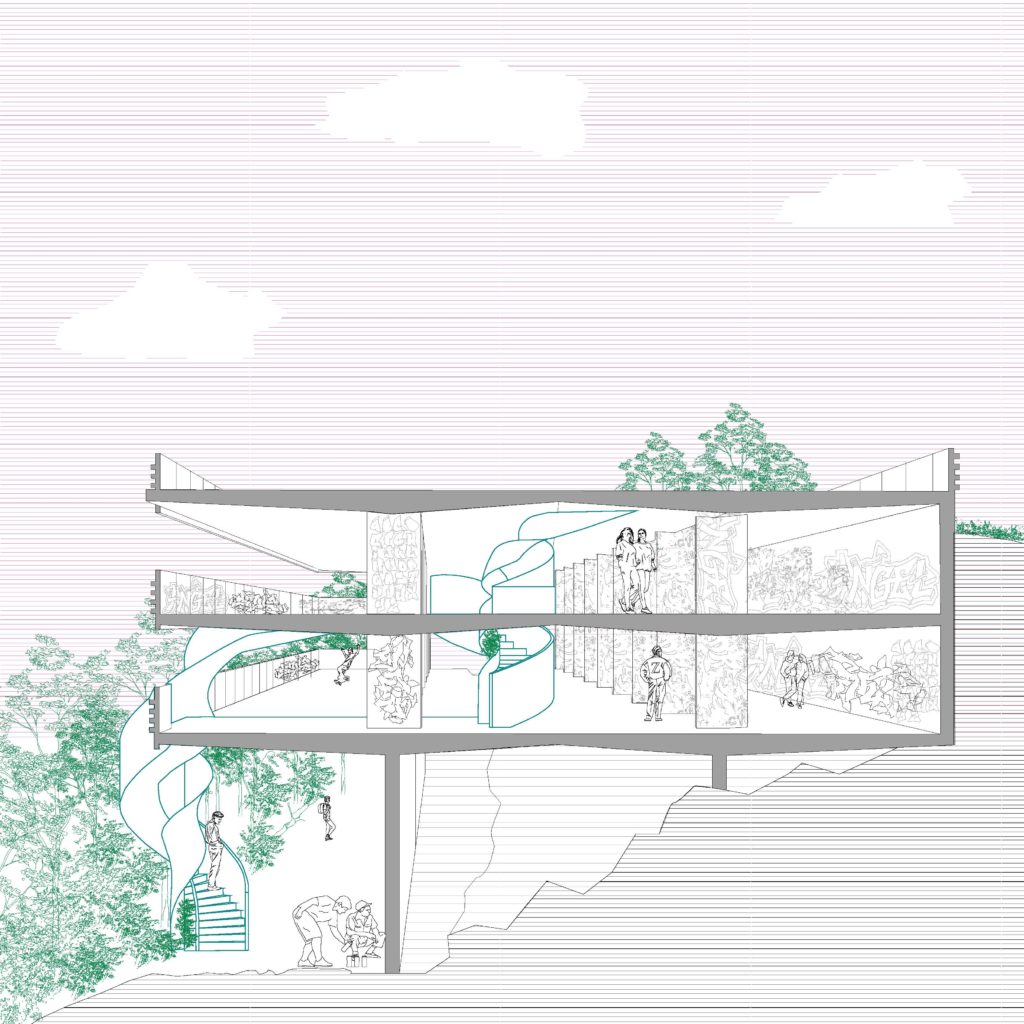

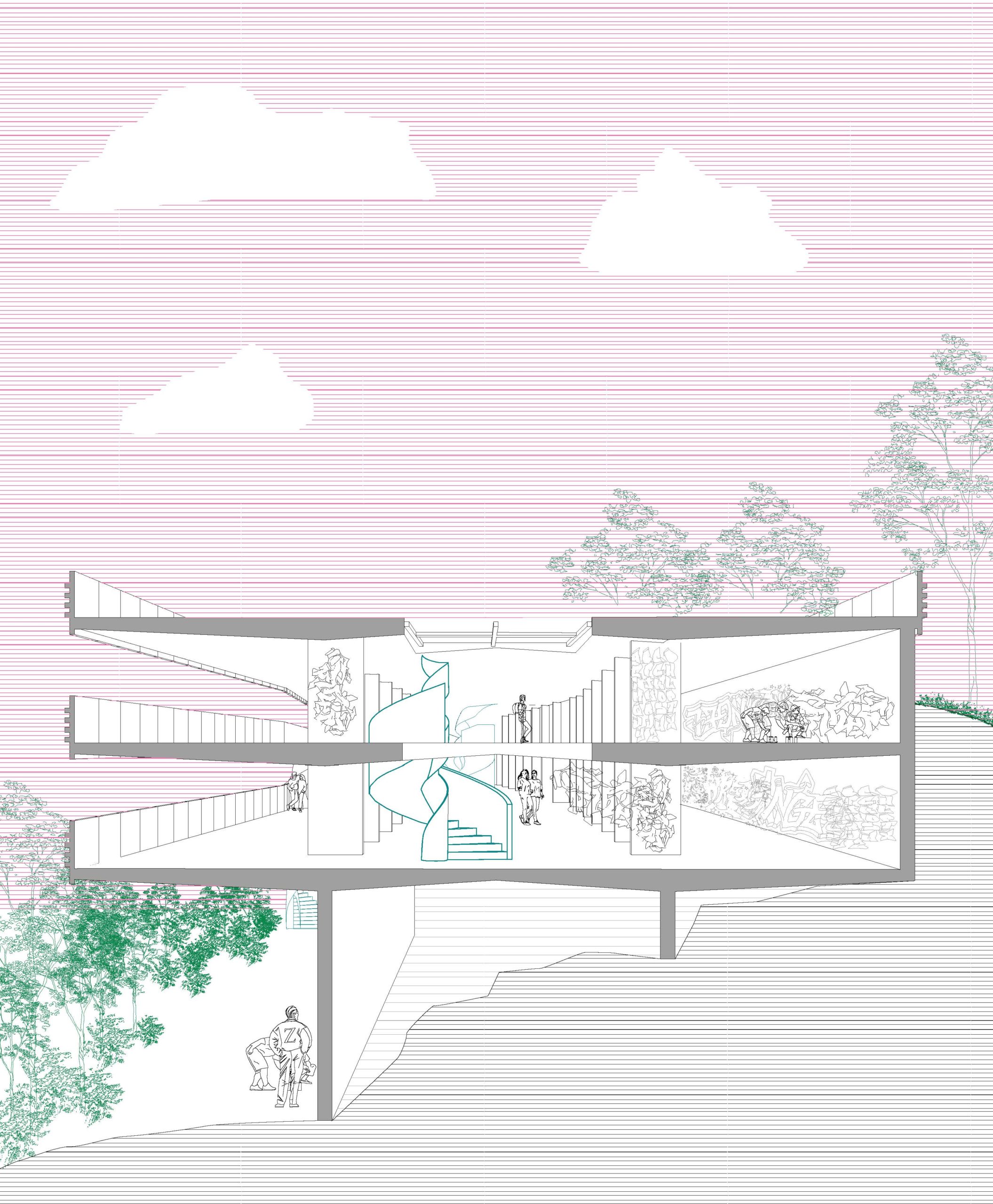

When approaching sub-cultures, an informal way of communication needs to be established. Through the acts of the grounded theory, spatial patterns and behaviours can be comprehended and design solutions extracted. Through the 1:1 mock-ups, the design solutions can be better tailored to the two different social groups. To protect the sub-culture from becoming an object, a small division is still required where the sub-culture can have autonomy over its own space.