ARCHITECTURE DESTROYS NATURE?

rebuilding the human-nature connection

Does architecture destroy nature? According to the United Nations, about 60 percent of the world population is soon to be expected to reside in urban environments. This unprecedented development does not only drive forward the urbanization of rural areas but also the densification of cities. A progression that promises better housing, education, healthcare, productivity, and opportunities for the population, however, it is also a progression largely responsible for the disconnection between people and nature.

This thesis emphasizes the importance of the human-nature connection and explores an alternative approach to sustainability within the field of architecture. It explores ways to reconnect to nature or strengthen the connection between people and nature to foster pro-environmental behavior, rather than focusing on “sustainable” building performance or materials.

While nature connectedness has been identified as a central determinant for well-being and health, for pro-environmental behavior, and positive child development, there is a need for further investigations on how nature connectedness can be achieved or how strategies for the reconnection with nature could be developed. Architects realized their responsibility and are using biophilic design elements to bring back nature experiences to the urban setting. However, the experience of nature alone does not lead to a strong human-nature connection. Research suggests that the relationship between humans and nature is strongest when developed from an early age. Thus, introducing strategies for reconnection to the context of child development will be further investigated.

This thesis aims to transfer evidence and research on the human-nature connection from philosophical, psychological, socio-economical, ecological, and sustainable sciences into concrete design strategies relevant to the future discourse on sustainable architecture. Finally, these design strategies will be implemented in the context of an urban interpretation of a forest kindergarten, that has the potential to affect the whole area and society.

TABLE OF CONTENT

Can architecture reconnect people to nature?

What is nature?

What is our connection to nature?

Why is our connection to nature important?

What disconnects us from nature?

What reconnects us to nature?

How can architecture reconnect people to nature?

the forest kindergarten

project context

Site analysis

Building analysis

design proposal

Design concept

Biophilic design

Building transformation

Floorplans

Sections

Perspectives & Video

reflection

Findings

Contribution to the discourse

Copyright

Can architecture reconnect people to nature?

Even though sustainability in architecture has gained a lot of popularity and shapes the requirements for buildings in many competitions, architectural designs rarely focus on creating an enhanced human-nature connection. In fact, architecture usually disconnects us from nature while providing shelter and protection for people. So how can architecture reconnect people to nature? To answer this question a better understanding of nature, our connection to nature and its importance, as well as disconnecting and reconnecting elements, in general, is necessary and led to five guiding questions and objectives.

What is nature?

To understand the aim of this thesis it is essential to have a clear definition of what “nature” means in its’ context. It is a question that has been discussed by many great thinkers and philosophers throughout history, often together with what humanity’s place is in nature and how we affect it. One of the earliest descriptions of humanity’s relation to nature was made by Cicero, reflecting on how mankind treats, manipulates, and shapes the land, he differentiates the natural environment into a first and second nature. A wild, pristine, and untouched external nature which, through the human conquest and domination, becomes a different, manmade nature. This dualistic view of nature turned out to be one of the fundamental concepts for the future discourses on ecological, economic, and social development.

What is our connection to nature?

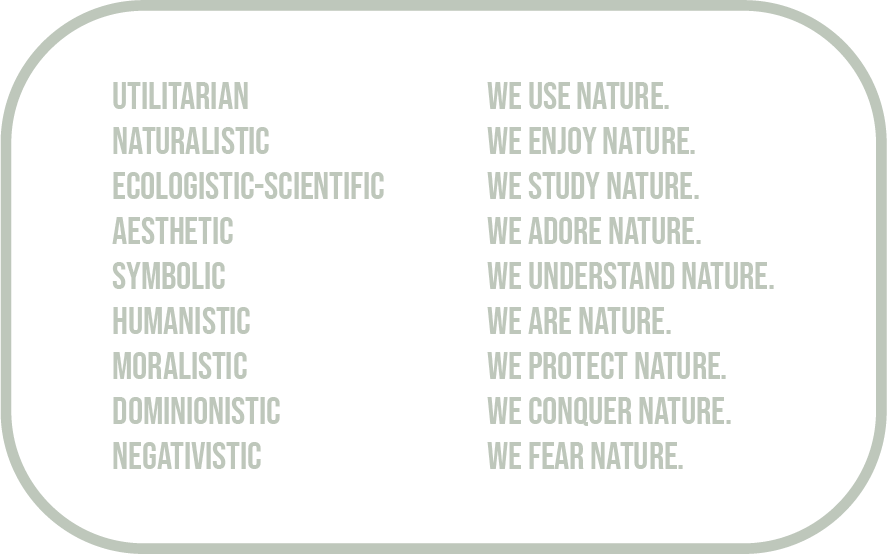

In addition to the biophilic values described in The Biophilia Hypothesis, there is another concept that uses five categories of connection to nature, namely material, experiential, cognitive, emotional, and philosophical connections. These connections can be categorized by two different measurements: the social dimension that indicates if a connection is subjective or applicable to larger social groups and the positioning of the connection that shows whether it is internal/mental or external/physical. Of course, the connection to nature is generally subjective and different for everyone, however, it is based on the same natural element perceived differently.

Regardless of individual beliefs and values, there is a trend in modern society and modern lifestyles that weakens certain connections to nature while strengthening others. Knowledge and understanding, symbolic value, emotional attachment, and responsibility for the natural world yielded to the globalized, fast-paced society and a digital lifestyle which took over nature’s role as an always present part of daily life. A lifestyle that is based on consumption – the utilitarian and materialistic connection to nature – and promotes nature connections as leisure activities rather than an integrated part of people’s life.

Why is our connection to nature important?

Research has shown that the experience of nature promotes good health and affects our well-being not only on a physical but also a mental level. Roger Ulrich, an american researcher who populized evidence-based design, conducted a study on the connection between pain drug doses and nature views of hospitalized persons and laid the ground for many more studies on the importance of nature for humanity. The results of the

study suggested that patients with a view on nature need fewer pain killers than people with a view on a brick wall. While this effect of our connection to nature is easy to measure and offers an easy to understand example of how nature can affect our well-being, it is very specific and limited in its’ scope. The interest in researching the effect of nature on health and well-being but also the importance of the human-nature connection as a driver to affiliate with nature has been the topic of many recent research papers. However, a new dimension of people’s connection to nature has been added in many recent research papers. Besides benefits for health and cognitive development, a strong human-nature connection leads to pro-environmental worldviews and an increased willingness to make sacrifices for environmental benefits.

What disconnects us from nature?

Modern society reshapes landscapes, designs cities, and urban environments, and controls many natural elements at will. According to the United Nations, about 60 percent of the world population is soon to be expected to reside in urban environments. This unprecedented development does not only drive forward the urbanization of rural areas but also the densification of cities. A progression that promises better housing, education, healthcare, productivity, and opportunities for the population, however, it is also a progression largely responsible for the disconnection between people and nature. The competition for space leaves little room for nature and combined with busy modern lifestyles it is likely to result in a decline in experiences of the natural world. The lifestyle that came along with modern cities and globalization is defined by consumption, mass media, and technocratic values that represent “city life”. With food being bought and a constant availability of seasonal goods, the impact of resource consumption is hard to understand. Complex logistic chains further this confusion of humanities impact of consumption. This “urban culture” is produced, packaged and advertised as a part of citizens leisure time instead of being infused by the daily life and tradition. The weakened connectedness to nature resulting from this urban environment can be held responsible for a weak human-nature connection, thus, also responsible for a lack of knowledge and empathy for nature. However, this does not mean that there is no nature in urban environments. In fact, nature can be encountered almost everywhere in cities. Contact with wildlife, flowering plants, trees, or beautiful sunrises and sunsets lets most people wonder at the beauty of nature. On the other hand, cities and their fast-paced lifestyles often don’t leave time and space for these encounters.

What reconnects us to nature?

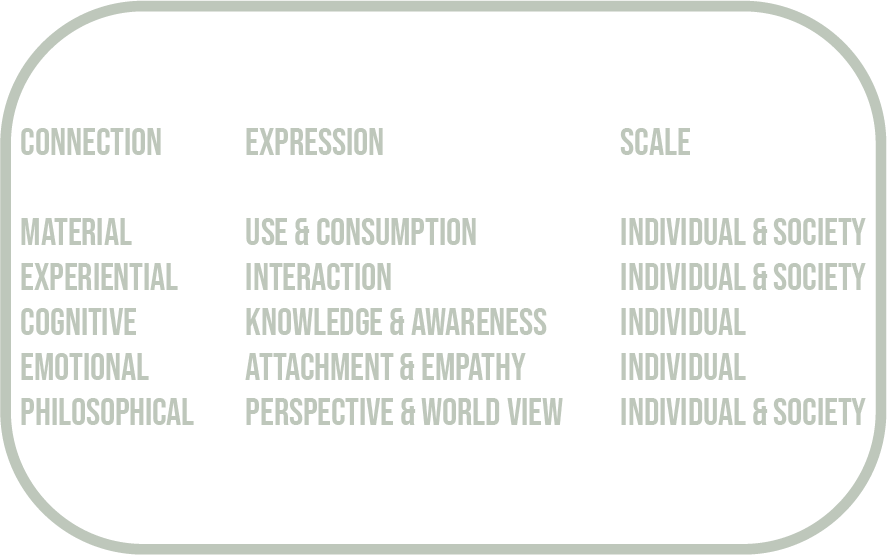

The concept of leverage points is inspired by Donella Meadows who described how various adjustments to parameters, rules, and information flows can change entire systems. This concept has been adapted to the five connections to nature – material, experiential, cognitive, emotional, and philosophical – and organizes these connections from shallow to deep leverage points according to their potential to strengthen the human-nature connection. The material connection holds the least potential to reconnect people to nature as it is based on the consumption and use of resources, thus, offering only little potential to connect people to nature. The experiential connection offers more leverage as it fosters direct interaction with the natural environment, however, just the experience of nature has less impact than the cognitive, emotional, and philosophical connection. Knowledge, awareness, and environmental beliefs are part of the cognitive connection. Empathy and feelings of attachment are part of the emotional connection. And finally, our worldview, which greatly defines how we behave and how we treat our environment, is part of the philosophical connection.

These connections offer the best leverage point to transform individuals and culture towards a more sustainable society, however, changing the cognitive, emotional, and philosophical connection of people to nature is difficult, even more, during adulthood. Thus, targeting these connections during early childhood is more likely to lead to a strong and stable human-nature connection as an adult. For example, children that visited forest kindergartens created a deep connection to nature during their childhood and are more likely to have pro-environmental beliefs during adulthood. The potential of forest kindergartens will be explored further and put into an urban context. Combined with biophilic design and a partly public program, it aims at reconnecting a larger group of people to nature.

How can architecture reconnect people to nature?

Seeing architecture as something that destroyed many natural environments in the way that it claimed its’ space and transformed it into an entity of the urban development leads us to the question of how something that takes away nature spaces can reconnect us to it. I don’t think that architecture alone can rebuild the connection between people and nature, however, I do think that it has an essential role in the process of reconnection. Using architecture to recreate nature experiences in the urban environment focuses on the experiential connection between people and nature, thus, using a weak leverage point to achieve changes towards a sustainable society. On the other side, using architecture to create environments that host pedagogical functions that build up emotional attachment and philosophical values towards nature can be an effective measurement to strengthen the human-nature connection. With the combination of architecture providing natural features in the urban environment and pedagogical functions or practices to make use of these features, there is an opportunity to foster change in our society. However, the design profession alone cannot achieve this combination of space and functionality without convincing stakeholders of its importance. After all, architects design buildings and urban spaces based on the programs and functions defined by clients and stakeholders which makes it even more important for architects to argue for design elements that feature natural elements regardless of their practical functionality.

The forest kindergarten

Forest kindergartens focus entirely on the experience, exploration, interaction, and connection to nature. Letting children build up this intimate human-nature connection leads to pro-environmental behavior and a strong feeling of responsibility for nature in adulthood. While it is difficult to build this connection during adulthood, where people’s characters and values are already shaped, the concept of forest kindergartens already starts at the very beginning of human development. The forest kindergarten evolved during the 1960s in Scandinavia and gained popularity especially during the 1990s, with strong development in Germany. Nowadays, forest kindergartens emerge all over the world. Forest kindergartens put an emphasis on the natural outdoor experience and schedule 75% to 100% of the day for outdoor activities. The characteristic feature of forest kindergartens is the full immersion into the forest without any boundaries like walls or fences. Nature preschools adapted this concept but put it into the context of urban nature centers and combine it with a mix of 50% outdoor activities and 50% indoor activities. Both concepts became more popular recently and in times of dense urban environments, the benefits of open spaces, fresh air, and natural features are recognized by many childhood educators. The early experience and bond with nature serve as a foundation for environmental values that lets children mature into responsible adults.

A key question for every nature-based program is the location. Especially in dense urban environments, it is very difficult to find a space that can accommodate the functions of a forest kindergarten while being in reach to families and children. Thus, most kindergartens and schools tend to naturalize spaces instead of aiming for the full experience and character of forest kindergartens. Especially the feeling of a borderless environment that can be freely explored by the children is hard to achieve in an urban setting, however, it is mostly because of the scepsis of stakeholders, parents, and officials that alternative concepts like forest kindergartens are not implemented on a regular base.

Project context

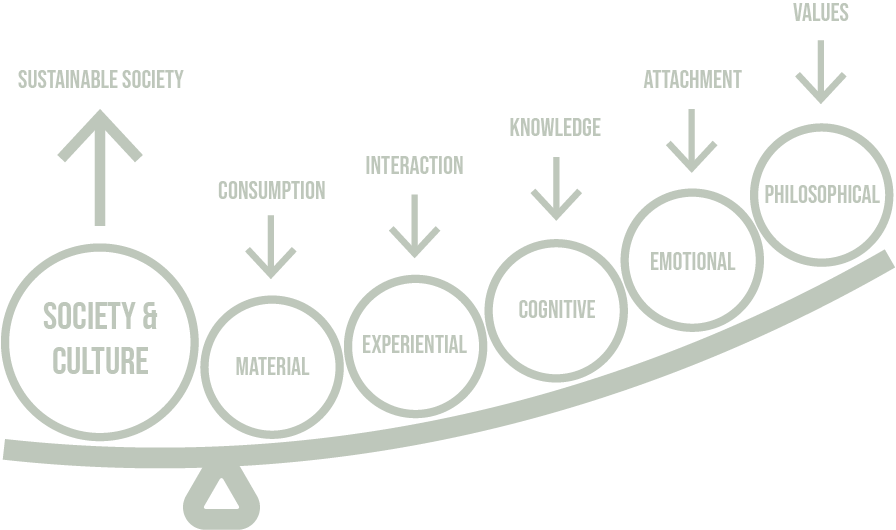

Swedens landscapes offer a great variety of nature ranging from mountains, tundras, and forests to lakes and long coastal areas. This abundance of nature is a direct contrast to Sweden’s current urban development. While large parts of the country are predominantly natural and leave many opportunities for nature experiences, cities like Malmö, Göteborg, and Stockholm have become center points for urbanization.

As Swedens second biggest city, Göteborg is a modern and industrialized city. With the Göta-älv river that runs through the city and the islands in front of Göteborgs coast, there is a strong topographic and historic connection to water. A large nature reserve that spreads out towards the south-east of Göteborg offers many opportunities to experiences forest flora and fauna. However, the city itself is shaped by the shipping industry, harbors, and dense urban fabric.

Site analysis

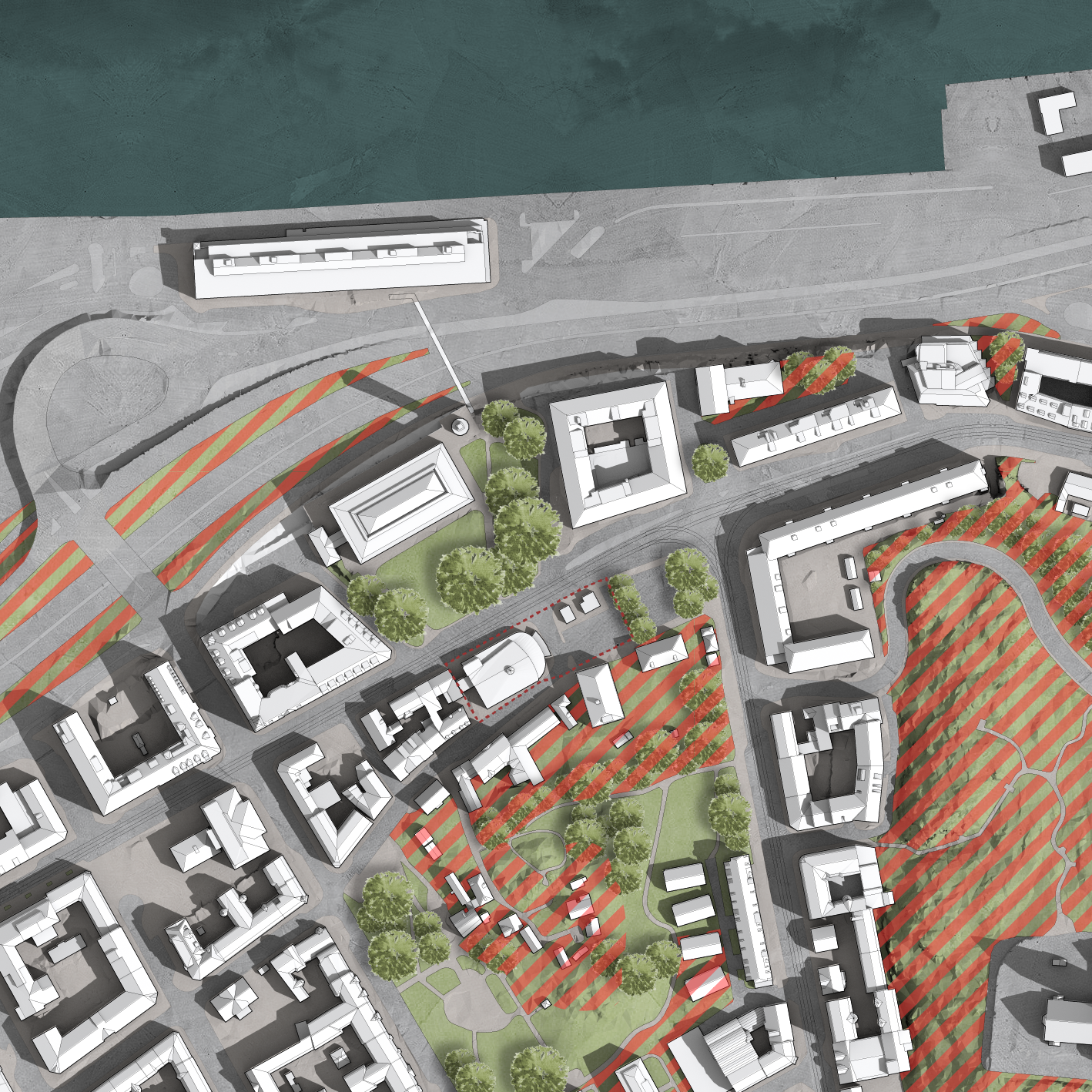

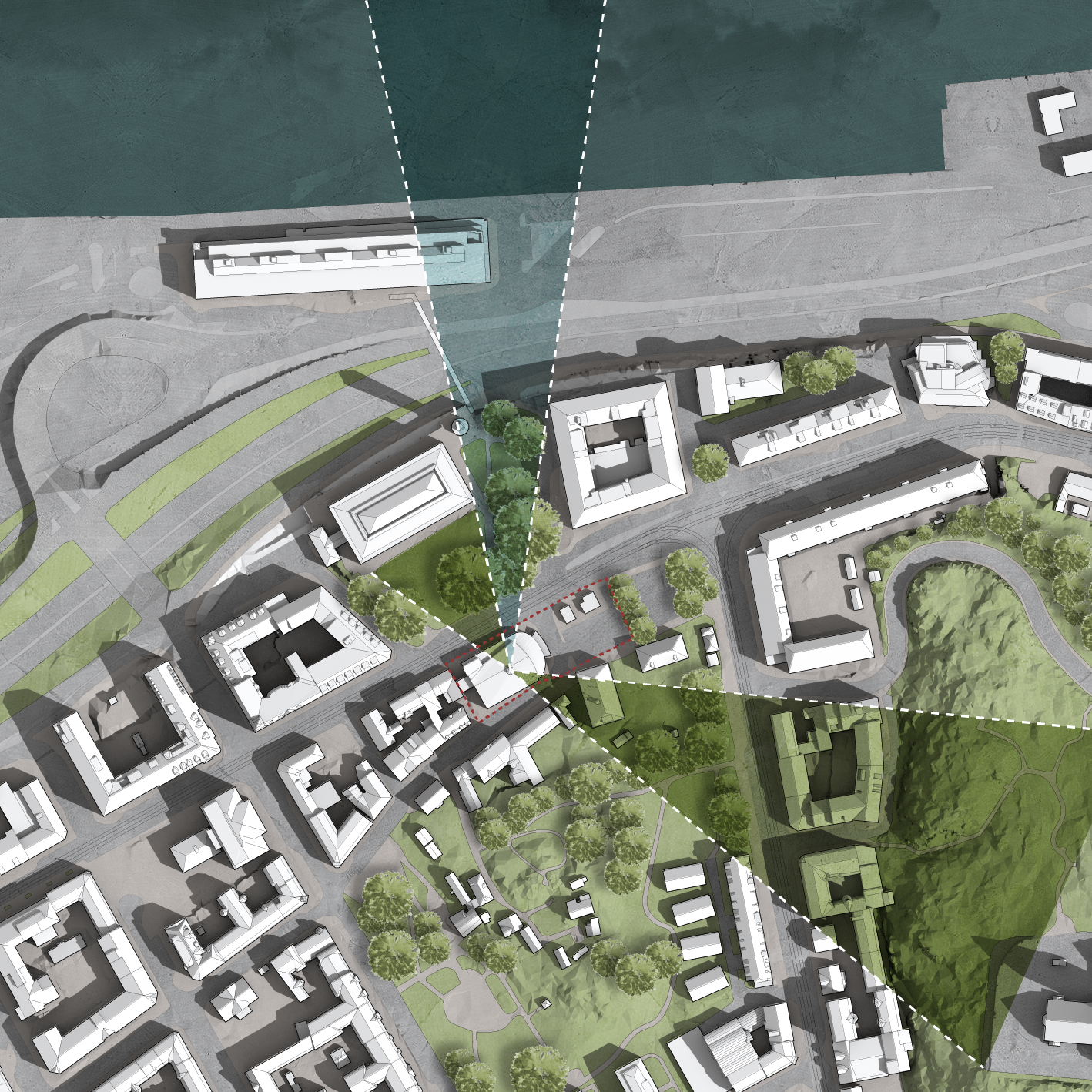

To explore the concept of the forest kindergarten in an urban context, an existing building in a dense urban environment is selected. The site is located in Gothenburg and combines features like water, hilly landscapes, historic context, and modern urban development. This combinations holds the potential to test implementing the forest kindergarten in a new setting.

The site of the project is located in Gothenburg’s city district Majorna-Linné in the area of Stigberget. The district is in close connection to the Göta-Älv river, however, the entire waterfront is occupied by industrial buildings and thereby not accessible as a nature retreat. To the south-east, the terrain becomes higher, rocky, and forms a relatively high hill that accommodates the church Masthuggskyrkan. To the south, there is a recreative green area with a small playground for children and to the west, a rather dense residential area starts. The center of this area is an old market place that is located in front of the historic Gathenhielmska building. Directly connected to that marketplace, a parking lot and the old Kaparen Biograf, a cinema from the 1940s, present a good opportunity for new development.

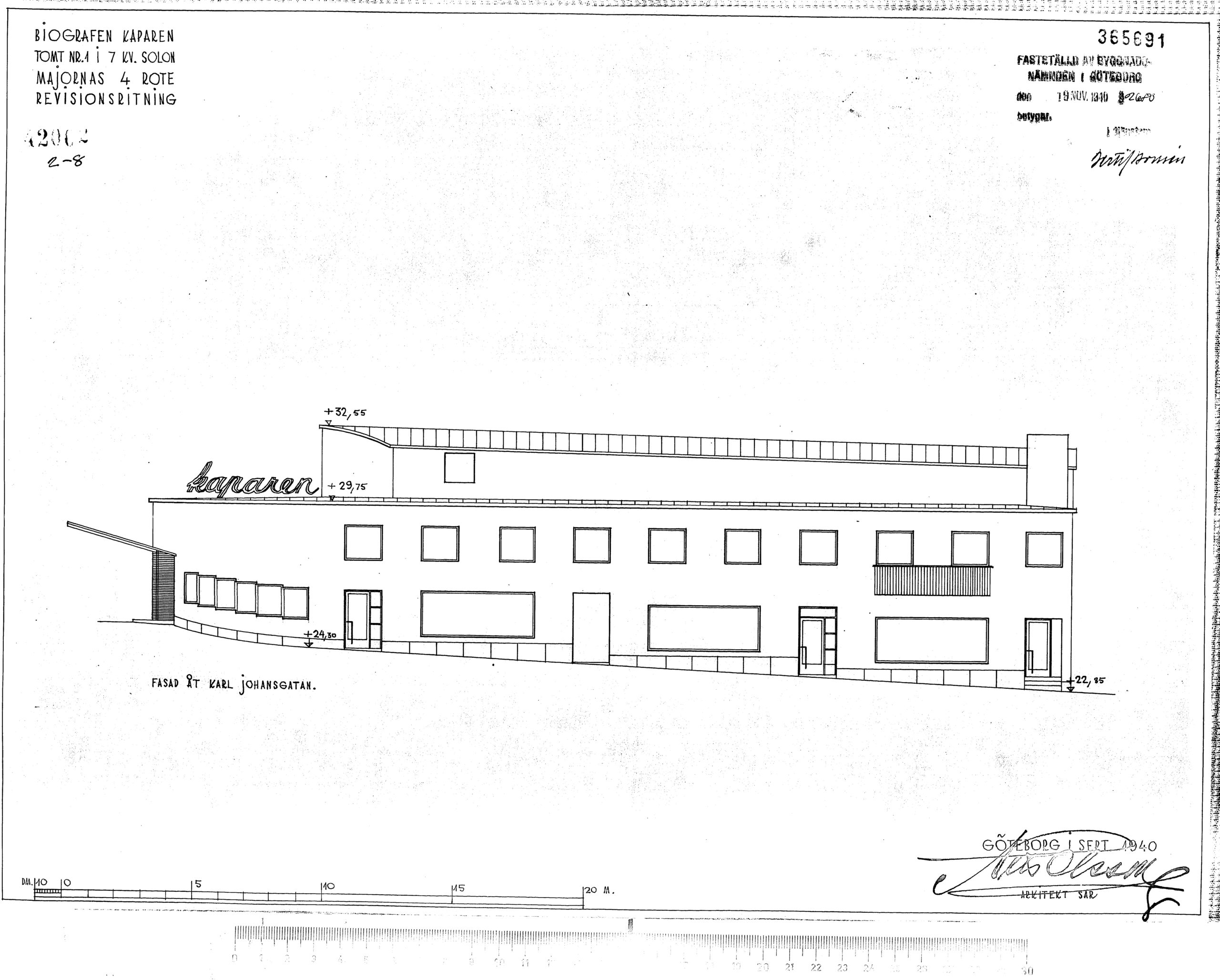

Building analysis

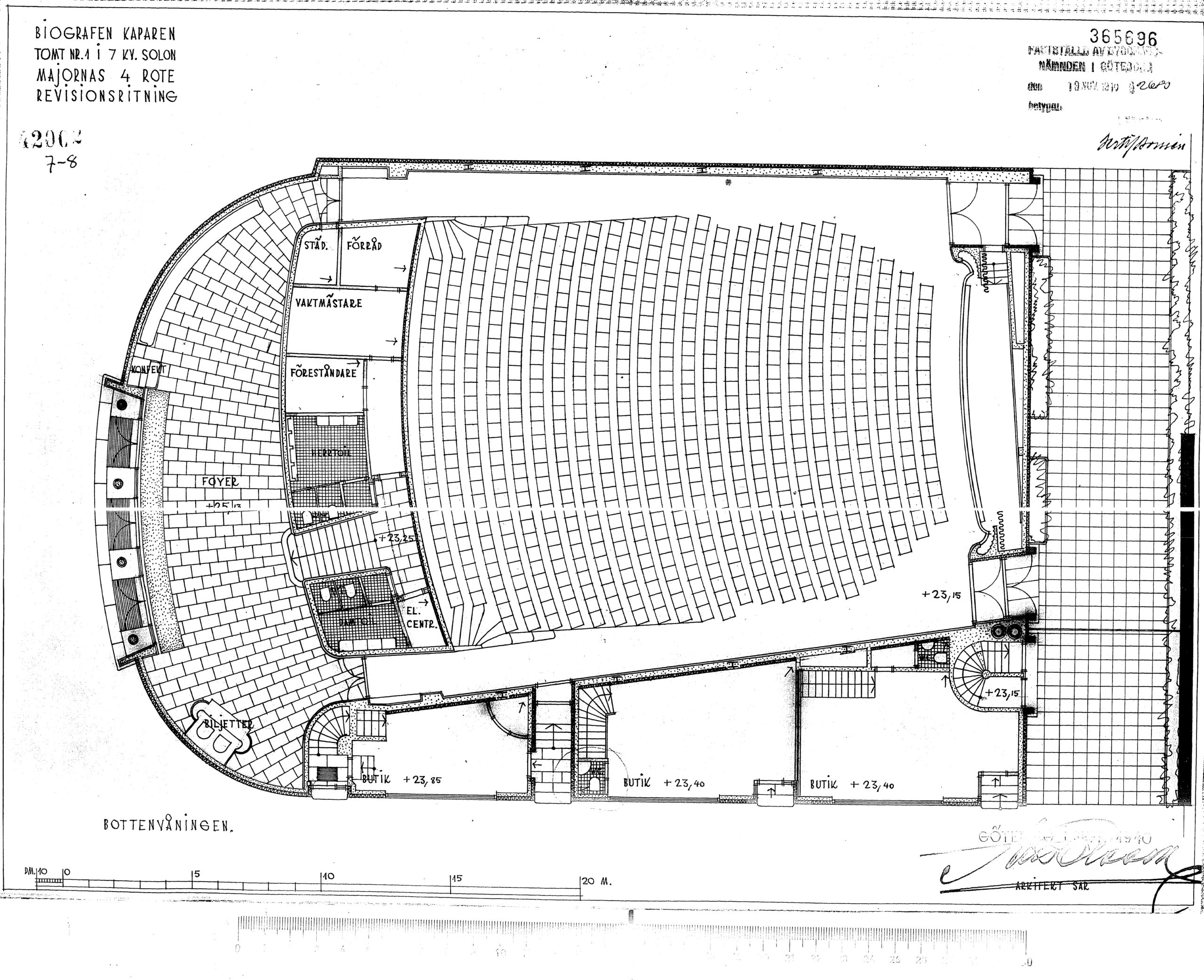

This old, almost historic, cinema was planned and constructed in the 1940s and got its’ name from Captain (Kaparen) Lars Gathenhielmska and the close vicinity to the Gathenhielmska building. The main entrance on the east facade guided visitors to the entrance hall of the cinema while three separate commercial areas found their place on the north facade and contribute other functions to the urban environment. The building has changed its’ functions several times during its’ lifetime.

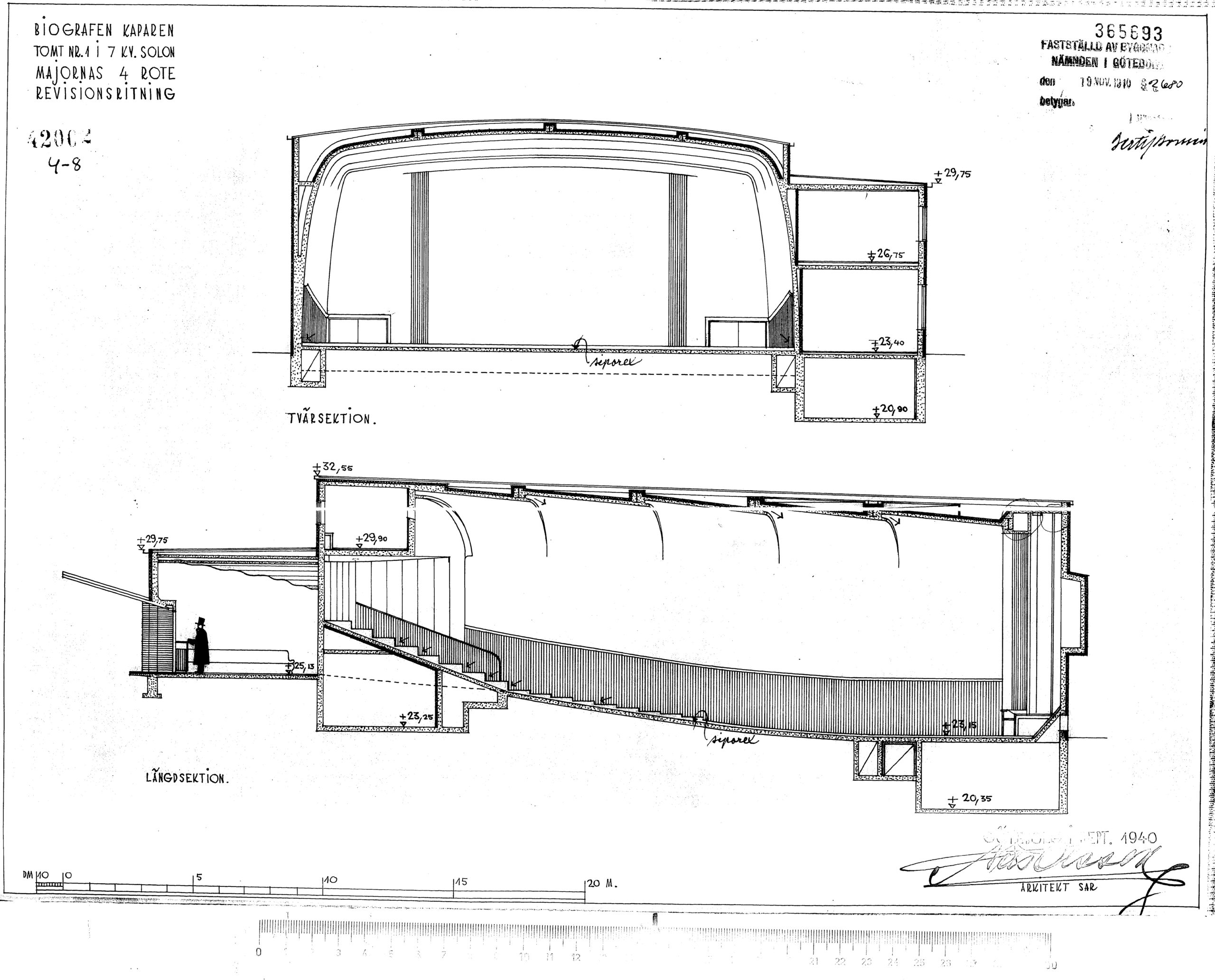

The biggest changes to Kaparen have been made during its transformation to a post office in 1984. The sloping floor of the cinema hall has been evened out to create a big open space that can accommodate several service points for customers of the post office. In addition to the changes to the floor, the entrance area has been reduced in its size and office rooms have been set up along the entrance room. Finally, the high ceiling of the cinema hall allowed for a gallery, thus adding another level to the building.

The changes made during the use of Kaparen as a supermarket from 2008 to 2009 are relatively small compared to the previous changes, however, it shows the flexibility that the building offers. The large open space that the cinema hall provides can host functions that require small rooms as well as large and open floorplans. The entrance area has become the cashiers’ point, the cinema hall has become the market hall, and the area below and on the gallery has become the warehouse and staff area of the supermarket.

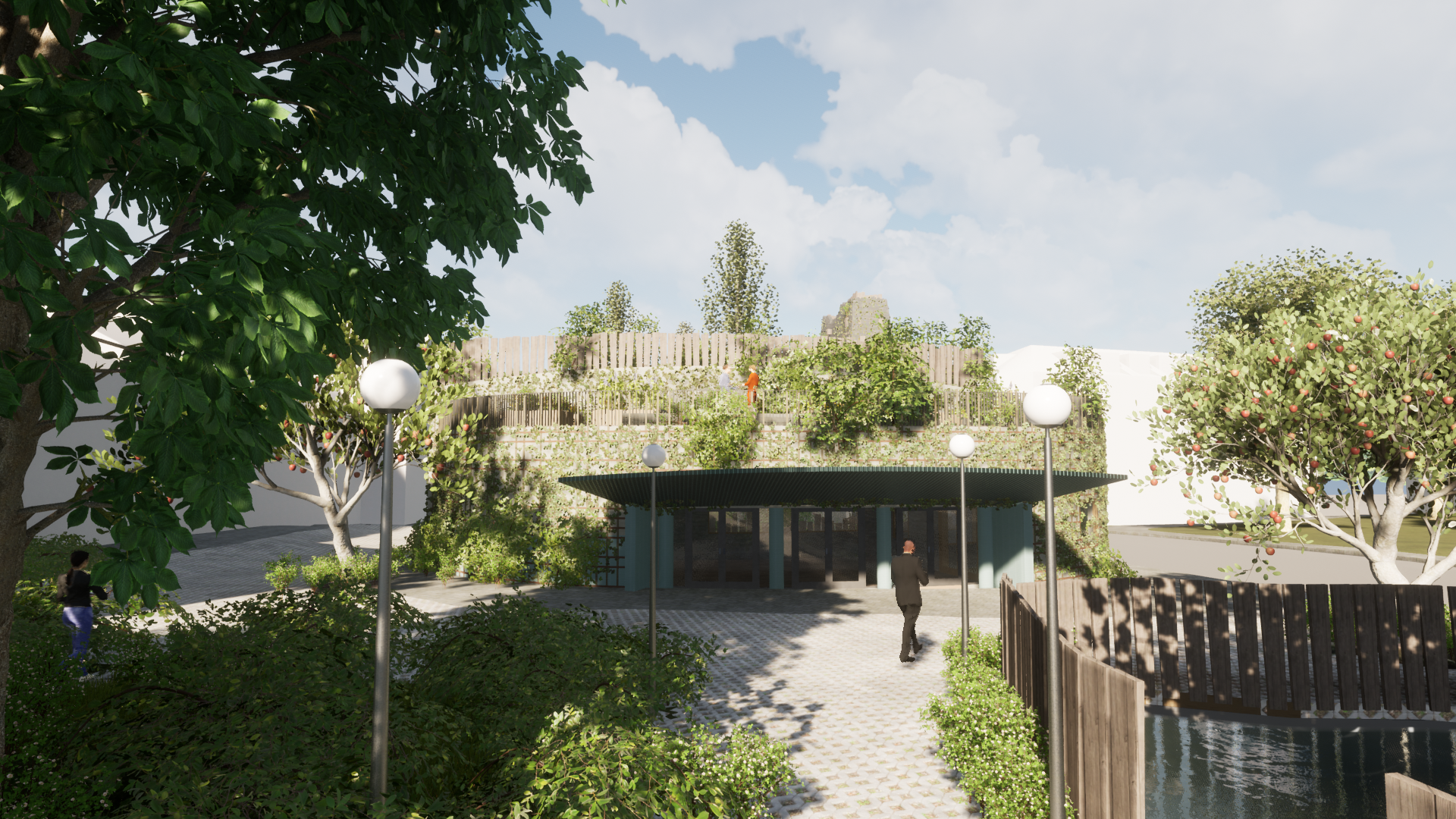

Design proposal

Since the usage as a supermarket, the old Kaparen building has been empty and waiting for a new function. Using the iconic building as a testing ground for an urban interpretation of the forest kindergarten for children between one and five years and a public green space where people can experience and connect with nature adds value to the surrounding area and makes use of the potential that the old cinema holds. By utilizing the large open space and the different height levels within the building it is possible to create an interesting and diverse environment for children to explore. As the description of forest kindergartens already suggested, children should explore the area and structure their days by themselves, thus, the program of the kindergarten should be flexible and include only necessary functional areas like toilets, staff rooms, and a kitchen. To create the connection between children and nature it is important to work on the different scales that have been presented in the theoretical part of this thesis.

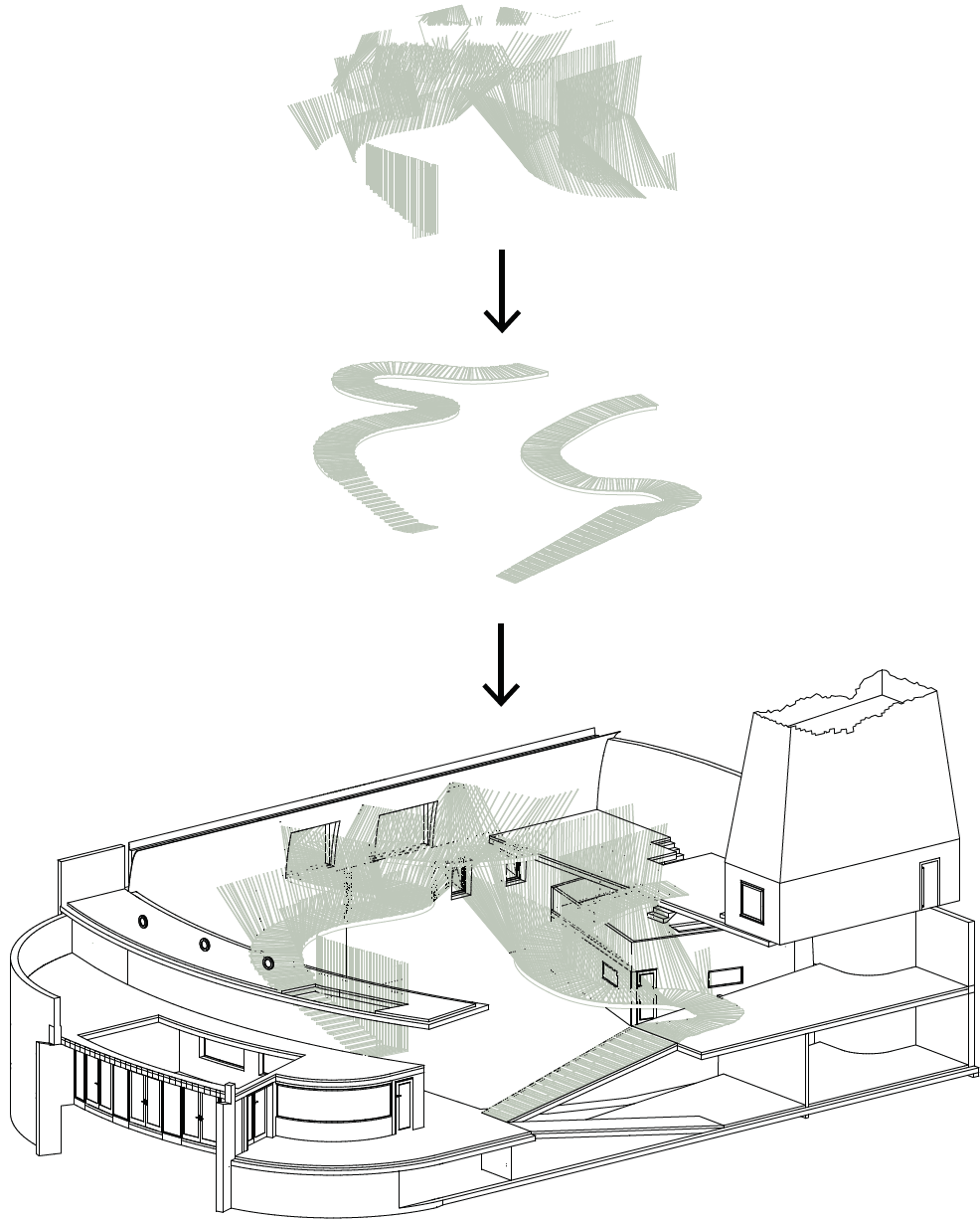

Design concept

A first step to create nature experience and make nature present in the design is to reveal the already existing nature in urban environments. This includes weather phenomena just as much as the flora and fauna that exist in cities. Including environmental features in architectural designs is a key strategy in this project. However, revealing the existing environmental features rather than just including new natural elements is important for creating an understanding of what modern urban environments do to nature and how normally suppressed natural elements find there way back into the city or building. This could include roots growing through the pavement, moss growing on the walls or roofs, animals nesting on the facade, or rain coming to the interior spaces.

In addition to revealing and introducing nature to the design, it is important to create spaces and areas that enable the children to experience and explore nature by themselves. This means that there has to be a variety of spaces and a playful, intuitive way of connecting the different areas. Areas that have different qualities and feature different natural elements that distinguish them from each other and convey different atmospheres for the kids to experience. However, experiencing nature alone is not enough to build up a strong connection to it during childhood. However, interacting with nature is even more important for a strong human-nature connection.

Interacting with nature is one of the best ways to create a strong human-nature connection. Fostering an active engagement between children and the natural environment through various activities builds a strong bond which in return leads feelings of affection and responsibility for nature. Interacting with nature can mean many different things and can range from playing with sand to growing plants or taking care of animals. Implementing different opportunities for interacting with nature will be a key to create the urban version of a forest kindergarten. The variety of zones, the playful and free pathways to explore the building, and the many spaces that enable nature to take a place in the building should create the feeling of an environment without boundaries.

The connection to nature is something that needs time to grow. Exposing children to natural features and engaging them in activities that include nature helps doing that from an early age on. In addition to the experiences inside Kaparen, it is important to also connect to the natural elements that surround the site. Creating a visual connection to the Göta-älv waterfront as well as to the Masthugget hill helps to make the topography more noticeable in the city.

Biophilic design

Biophilic design describes the transfer of the concept of biophilia to the design profession and the attempt to incorporate its values into buildings – an attempt that is rather difficult since our understanding of the human-nature connection still needs to be further explored. In the book Biophilic Design, a number of six design elements are presented that include around seventy attributes that can lead to a biophilic building. Several of these attributes are chosen based on the potential in them to create nature experiences and connections which take place on the building scale and the vicinity around it. References for these attributes offered a good starting point and inspiration for the urban forest kindergarten in Kaparen.

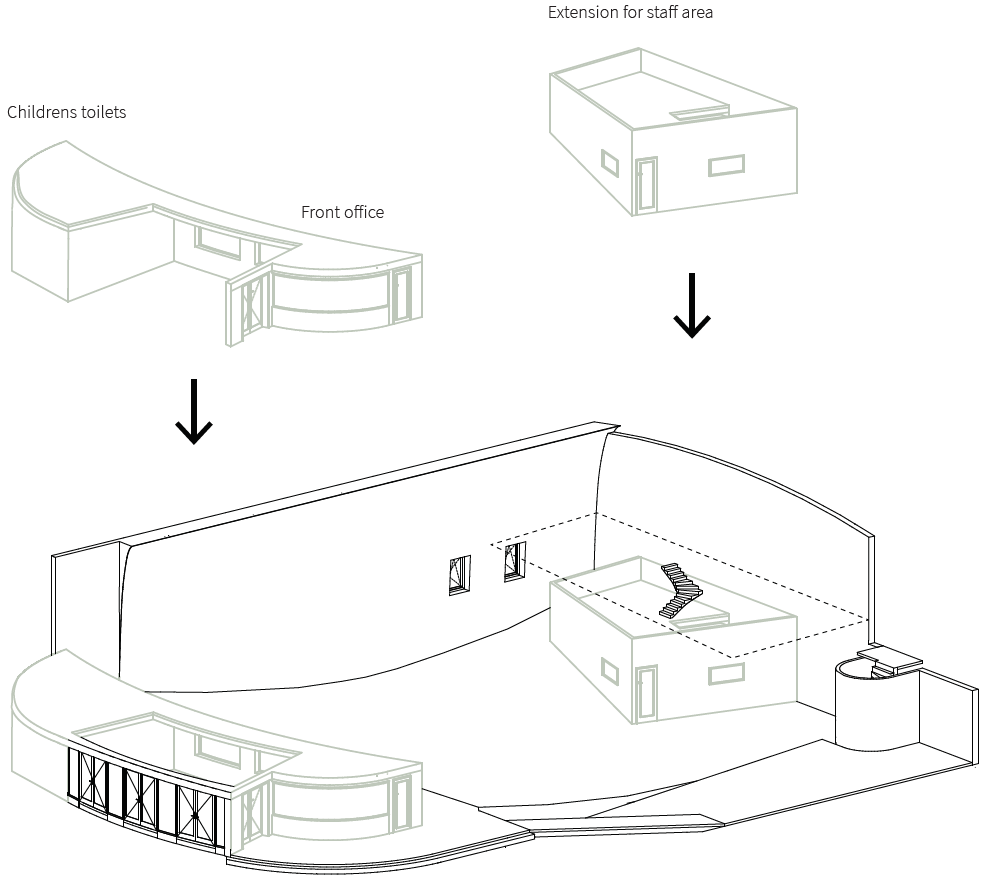

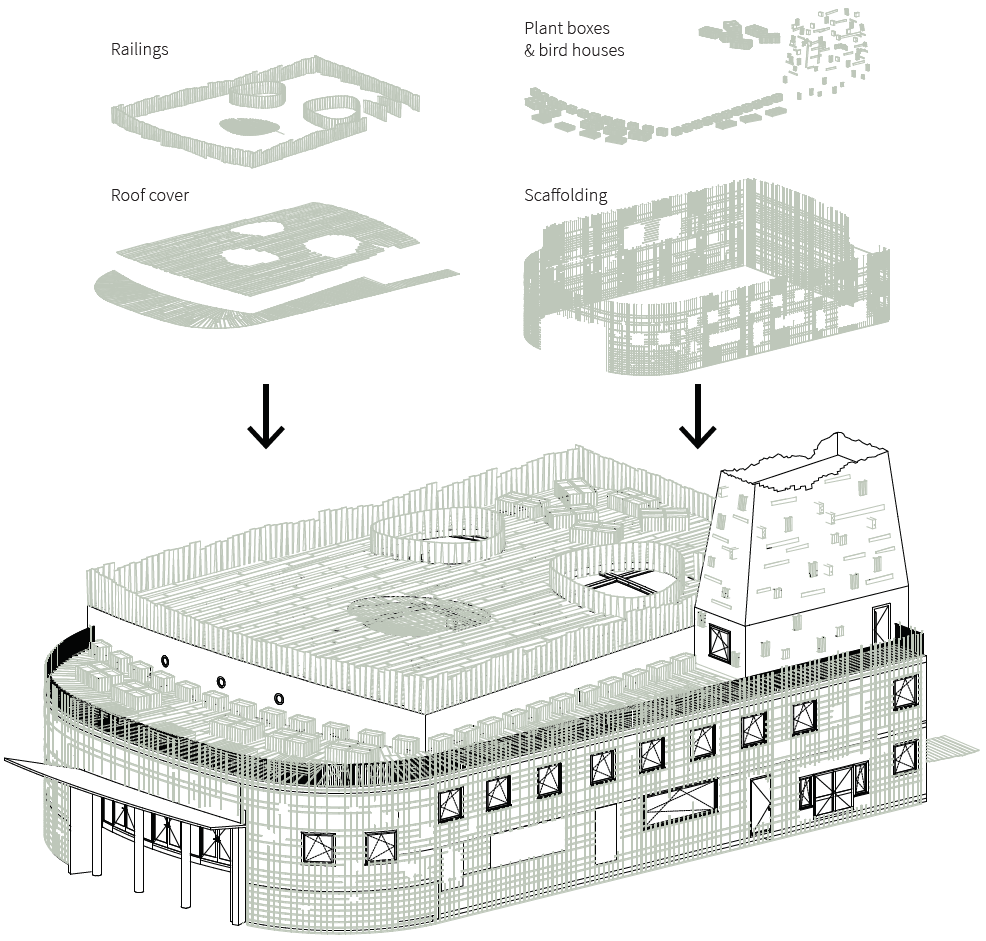

Building transformation

To create an environment with many natural features and plenty of ways to explore them the old building has to be transformed or at least extended with structures for plants to grow on and elements to make spaces more usable. The elements that have been added will be described step by step, however, the general concept is to enclose the building with a scaffolding that enables plants to grow on the outside and to create new openings in rooftop and facade to connect the interior spaces of the cinema with the outside. In addition to the transformations of the existing building fabric, there will be elements added that create new links between spaces, extend rooms of the cinema, or ensure the safety and user-friendliness.

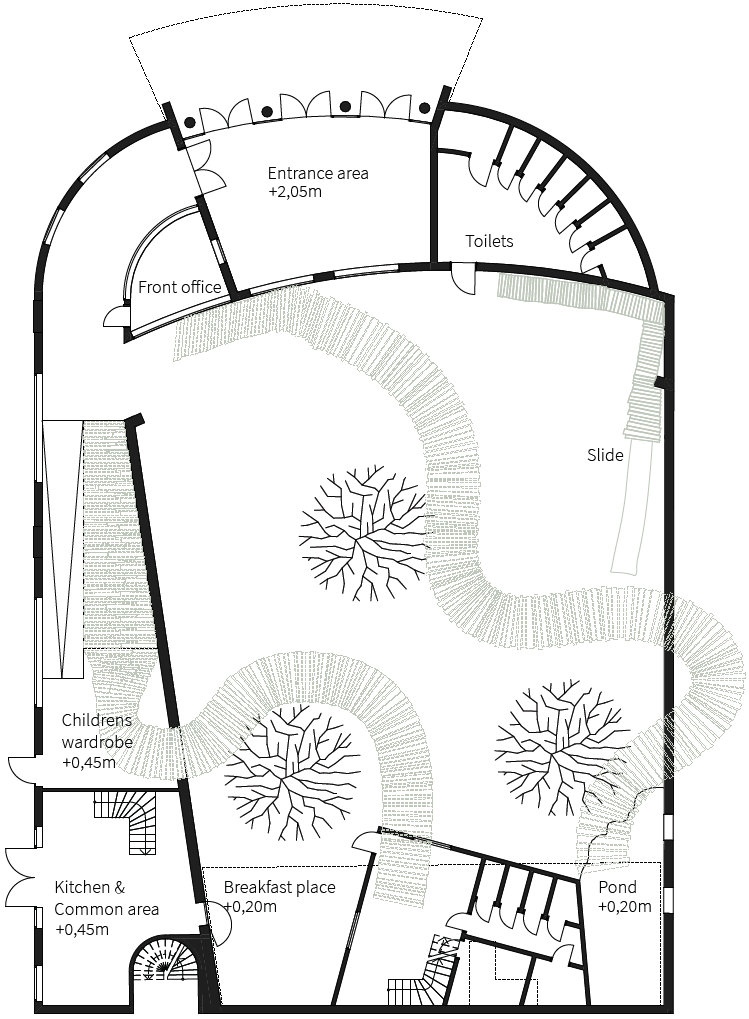

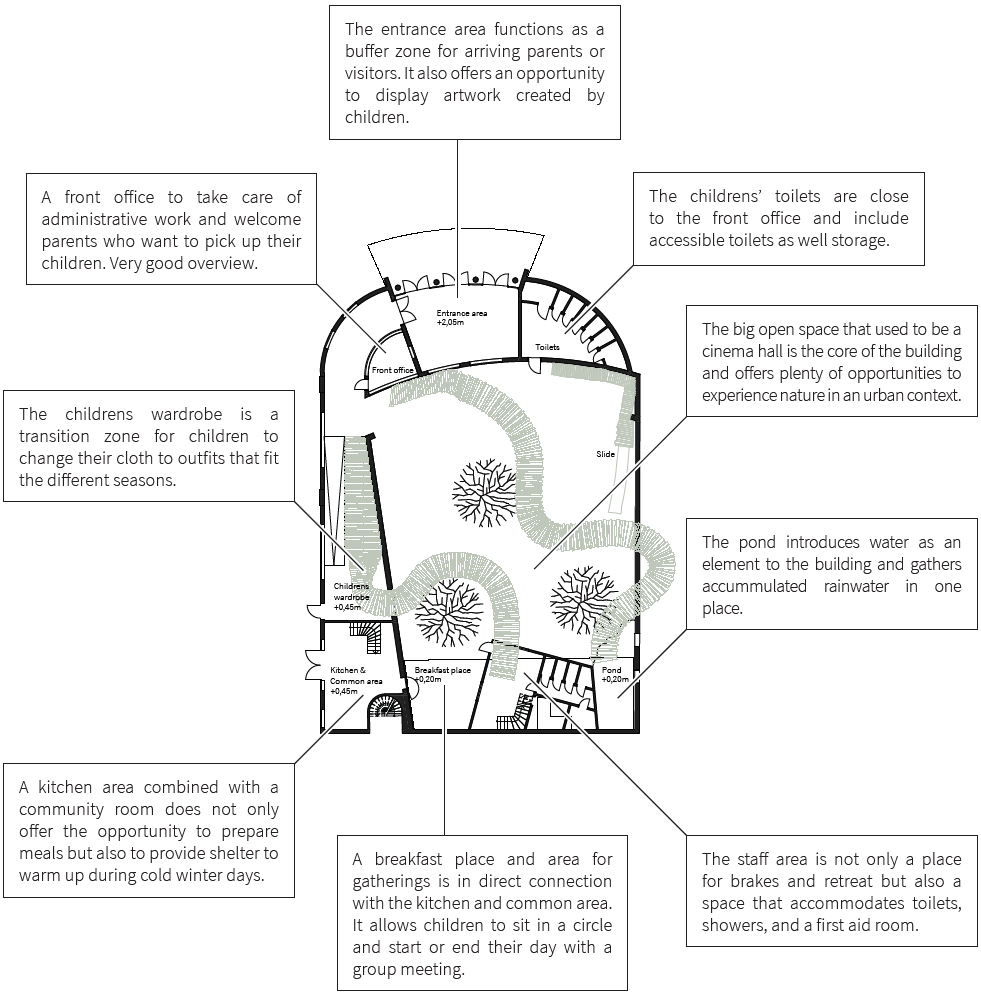

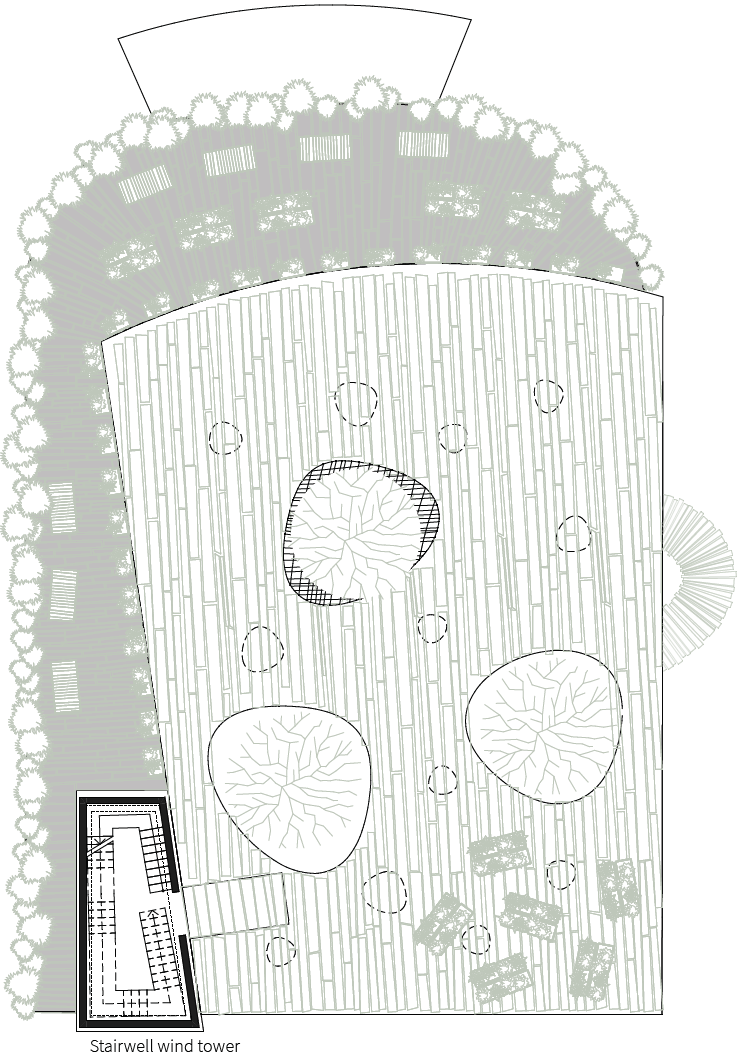

Floorplans

The entrance area, front office, and toilets are situated at the main entrance to the building. A door that leads to a short hallway along the front office separates the entrance area from the children’s space. The hallway ends in a junction that leads directly to the cinema hall and ramps to the lower part of the entrance level or first floor. A wooden scaffolding leads up to the midlevel that is on top of the front office and the toilets. At the end of the cinema hall, a kitchen and staff room are accommodated. The kitchen can be used as a sheltered common area during cold winter days, however, it should serve as a room for short breaks to warm up rather than an activity room since the children should spend most of their time in the open spaces of the kindergarten regardless of weather influences. A small pond in the corner of the building receives rainwater through the openings in the facade and adds another unique natural feature to the program. In addition to the break room, the staff area is equipped with toilets, a shower, a first aid room, as well as a stair that leads up to the area on top of the ceiling and the gallery on the first floor.

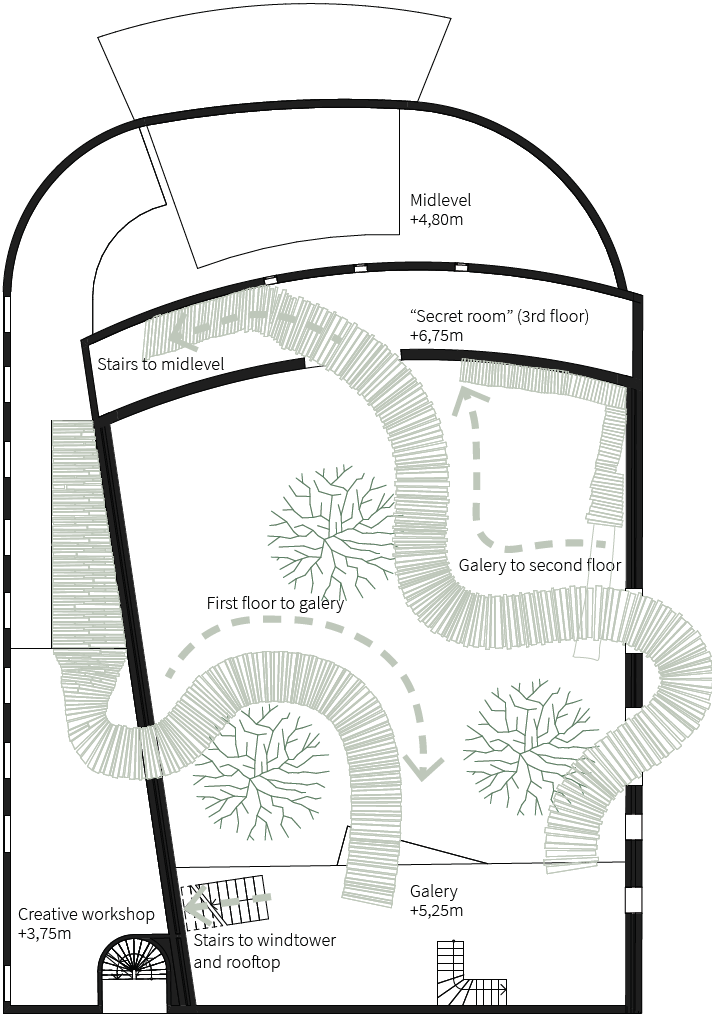

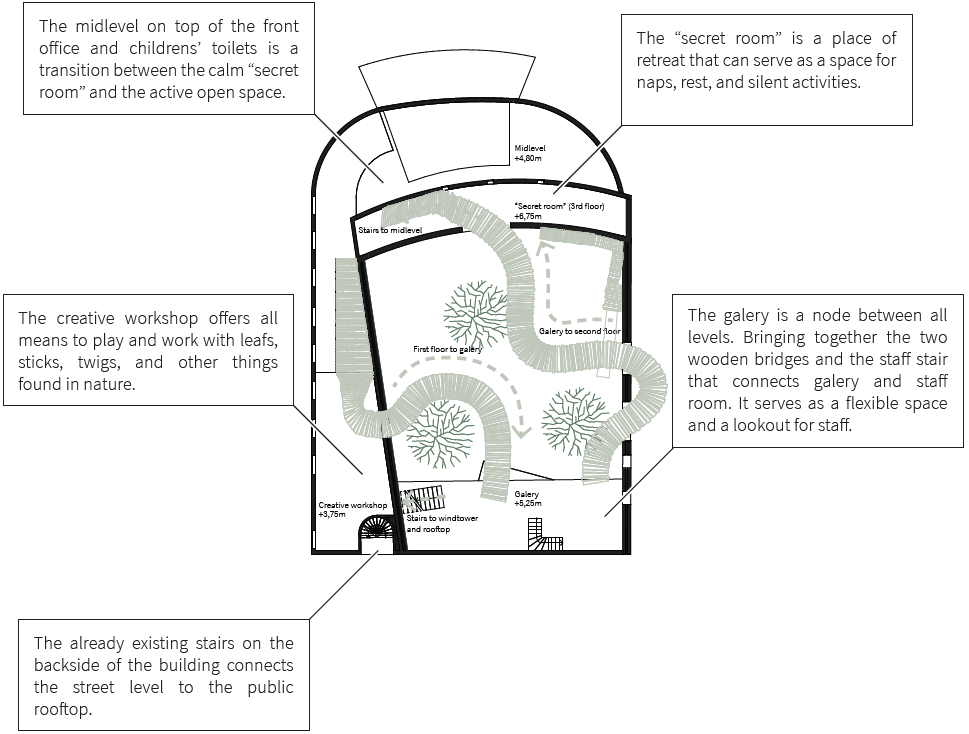

The second floor has several areas on different height levels. Starting with the ramp that leads from the first floor up children enter a workshop area for creative activities like tinkering with leaves, wood, and other natural items. The ramp continues from the creative workshop up to the gallery and leads over the suspended wooden bridge around one of the trees that is growing in the cinema hall. The gallery is a flexible space where many paths join each other. It is an access point to the wind tower, the rooftop, the staff area, and the second wooden bridge that leads up to an old technical room, a “secret room” for the children to retreat to when they want to take a rest from the more active zones. The pathway continues via a stair that leads down to the midlevel. This area is a transition zone between the calm “secret room” and the active ground floor. The midlevel also connects to the wooden scaffolding and slide that leads down to the cinema hall.

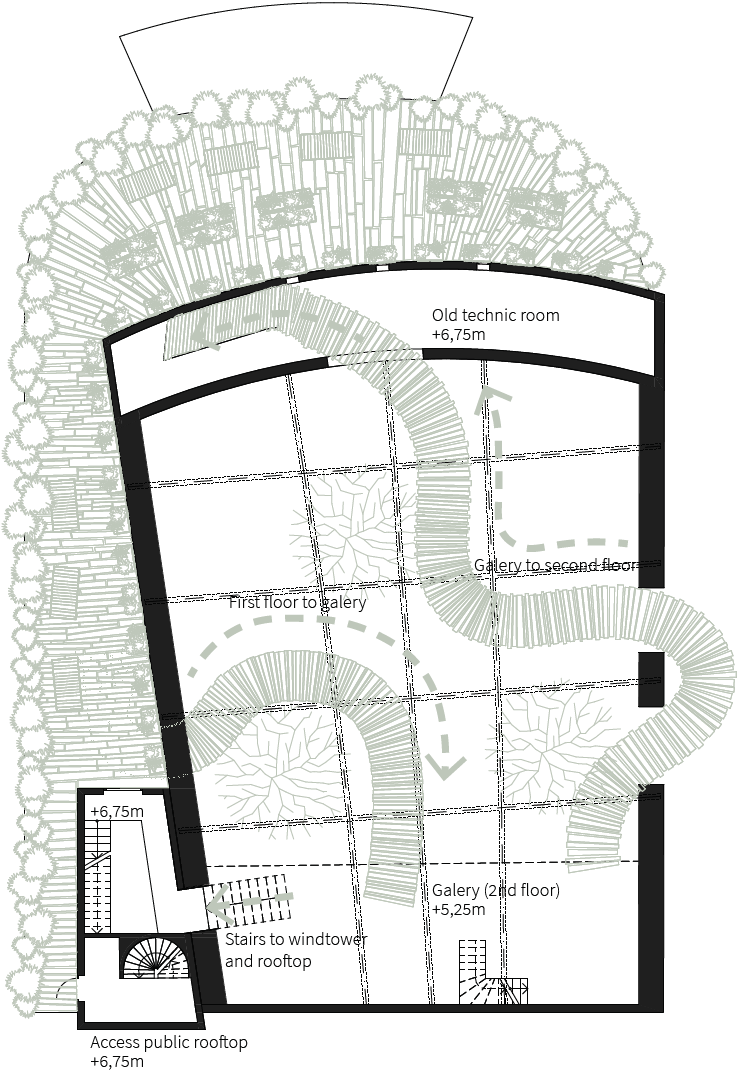

The public rooftop is accessible through the staircase on the west side of the building. It offers space for urban agriculture and meeting points for social activities. The plantation that overgrows the railing creates a filter between rooftop space and the surrounding urban environment, thus, blending out the city atmosphere. The public rooftop invites to retreat from the fast-paced city lifestyle and adds many natural features to the

surrounding are.

The upper rooftop is exclusively for the children and kindergarten staff. It can be accessed through the stairwell of the wind tower and accommodates urban agriculture elements as well as the opportunity to create a close connection to the trees growing inside the cinema hall. Together with the ground floor and the wooden bridges, and the rooftop there are three different levels of experiencing trees. The trunk at the bottom, the dense leafy area at the middle, and the tree crown at the top. To get even closer to the treetop a mesh of ropes is spanned over one of the openings in the roof that enables children to climb withing the highest points of a tree. The plant boxes for urban agriculture can be individually by the children to foster a feeling of responsibility for their own plants. Following the process of a growing plant and experiencing the feeling of satisfaction when it flourishes does not only create a strong relationship between people and nature, it also teaches the origin of many fruits and vegetables that we use to buy in supermarkets.

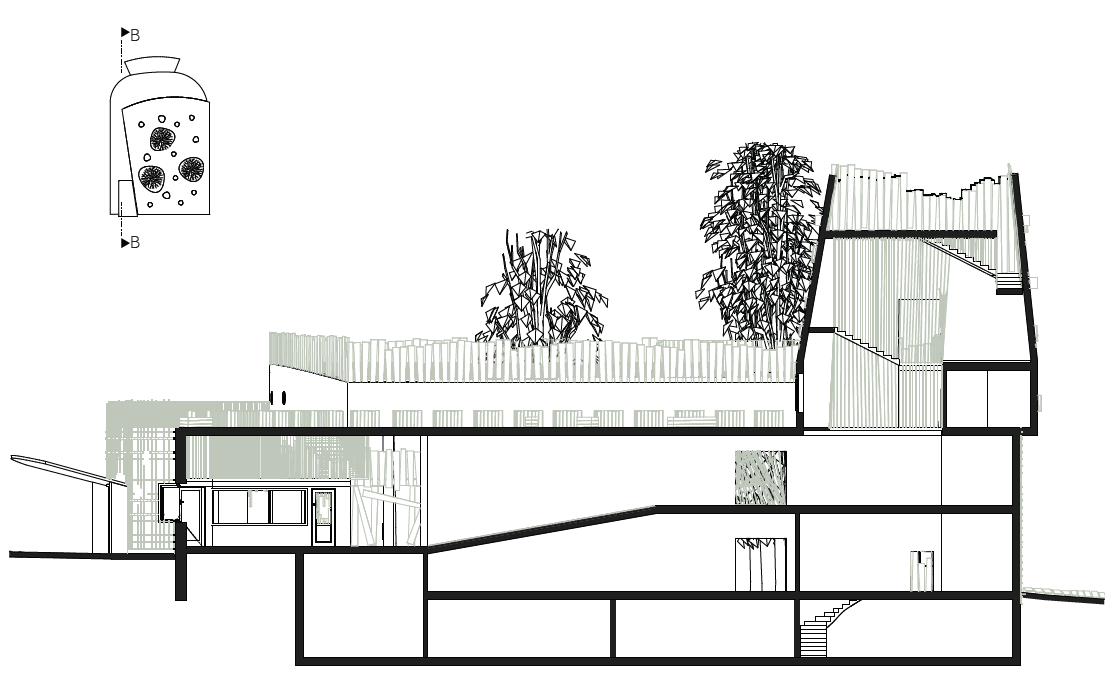

Sections

The section through the cinema hall reveals the generous size of the interior spaces and explains the many connections that now exist between the different areas. By taking out the floor extension that has been built for the past usage as a post office, the space becomes even larger and reaches a height that allows to suspend the wooden bridges without overwhelming the interior space. The lowest room height can be found with 1.70 m on the midlevel in the front of the building. However, this room height is more than enough for kindergarten children to use it, and even for the staff, it is suitable considering that this is one of the calm areas of the building.

Cutting through the wind tower and the ramp connections between entrance level and second floor show the interesting verticality that the tower creates. The stairwell is secured by ropes that span from the beginning of the stairs to the top of the tower. By opening up the roof between the beginning of the tower and the second floor it is possible to introduce the wind to the interior spaces. Especially while using the creative workshop, this can be a relaxing feature. The top of the wind tower functions as a viewing platform, however, by creating different heights in the brickwork of the wind tower, the views can be steered towards the Masthugget hill and Göta-älv river.

Perspectives & Video

Reflection

This thesis has investigated the relationship between architecture and nature to get a new perspective on sustainable design. A perspective that reveals the importance of the human-nature connection and the urgency of implenting this connection in architecture. To get a better understanding of how this implementation could look like, a closer look at the meaning of nature, our connection to it, and the importance of this connection has been taken. This created a good introduction to the topic and to the mindset behind this thesis. Design strategies have been inspired by this enquiry and transferred into the architectural context. An existing building in a dense urban environment has been chosen to implement these strategies to create a kindergarten that fosters a strong relationship between children and nature. Several elements that introduce nature to the building but also encourage children to explore and interact with nature. The design combines biophilic design attributes, functionality, and an

opportunity for children to explore nature in an urban setting.

Findings

The initial questions on nature and humanity’s connection to it have been described with a philosophical perspective on the topic. Doing this was a good introduction to the general idea and intention behind this master thesis: Emphasizing the importance of nature in human life and criticizing the prevailing unsustainable lifestyles that shape our society, as well as questioning the current and past architectural practice that led to the

urban environment as we know it. The research concludes that nature can be defined in various ways but ultimately describes the basic and unaltered material and lifeforms that our world is made off as first nature and the products that humans created from it as second nature. Modern cities and urban environments have been identified as a main driver for the extinction of nature experiences and the city lifestyles as a disruptive force between people and nature. Nature has been proven to be an important part of humanities development that is still connected to well-being, health, cognitive development. Relevant research papers have been evaluated to find strategies for strengthening the human-nature connection as well as reconnecting people to nature in general. Weak and strong leverage points have been identified and suggest that nature experiences alone do not have the potential to achieve a transformation in people’s behavior and in society. Last but not least, these findings have been used to answer the question if architecture can reconnect people to nature. In respect of the strong impact of urban developments on people’s connection to nature, there is an obvious connection between the design profession and the human-nature connection, however, the potential to affect this connection negatively is greater than the potential to affect it in a positive way. Architecture remains a crucial part of the development towards a sustainable society but it needs help from other professions and disciplines as it merely provides space for the functions demanded by clients. Being aware of this, it is the architect’s responsibility to argue for the inclusion of natural features in designs regardless of its profitability or functionality.

Contribution to the discourse

The discussion in this thesis aims to create questions about the current development of architecture, its’ sustainability approach, and society’s connection to nature in general. I think this thesis offers a new or at least an unusual perspective on architecture that has the potential to inspire architects, designers, and stakeholders to include more natural features and activities in design proposals and programs. The urban forest kindergarten shows that it is possible to combine functionality and the extensive use of natural features in an urban context, thus, offering a good example for future projects.

Copyright

The content of this website – images, graphics, text, etc – cannot be used without permission of the author. References to the work can be found in the endnotes of the booklet.

Copyright © 2020 Julian Kraemer. All rights reserved. Do not use without permission. E-mail: message.julian@outlook.com

2 replies on “Julian Kraemer”

Suuper

Like!! I blog frequently and I really thank you for your content. The article has truly peaked my interest.