Our point of view determines what we build

The way we look at housing greatly affects how society directs its resources. It is evident that the idea of housing as a human right has been predominant in times of great inequality and crisis, while naturally being somewhat forgotten during periods when the issue is less pressing. When looking at historical events regarding housing it is easy to see reoccurring patterns, like how the free market fuel issues of inequality and how the state therefore steps in in order to help those with weak positions on the housing market. The view on the dwelling has changed with times and preconditions, which shows in both policy making and in the physical cities of today.

Establishing common ground before immersing in a debate is important if we want to reach conclusions. Will we judge a building on its looks or its social intentions? The housing architecture of the social ambitions of the million dwelling programme has been heavily criticised while that of the 19th century’s distinctive class structures is predominantly praised. It is all a matter of point of view.

Is housing a question of architecture, economy or basic rights? Depending on what questions we ask we come to different conclusions about what is cause and what is effect; what is a matter of structures and what is a matter of events. The tricky part is to agree on which perspective should have precedence in city planning and policy making.

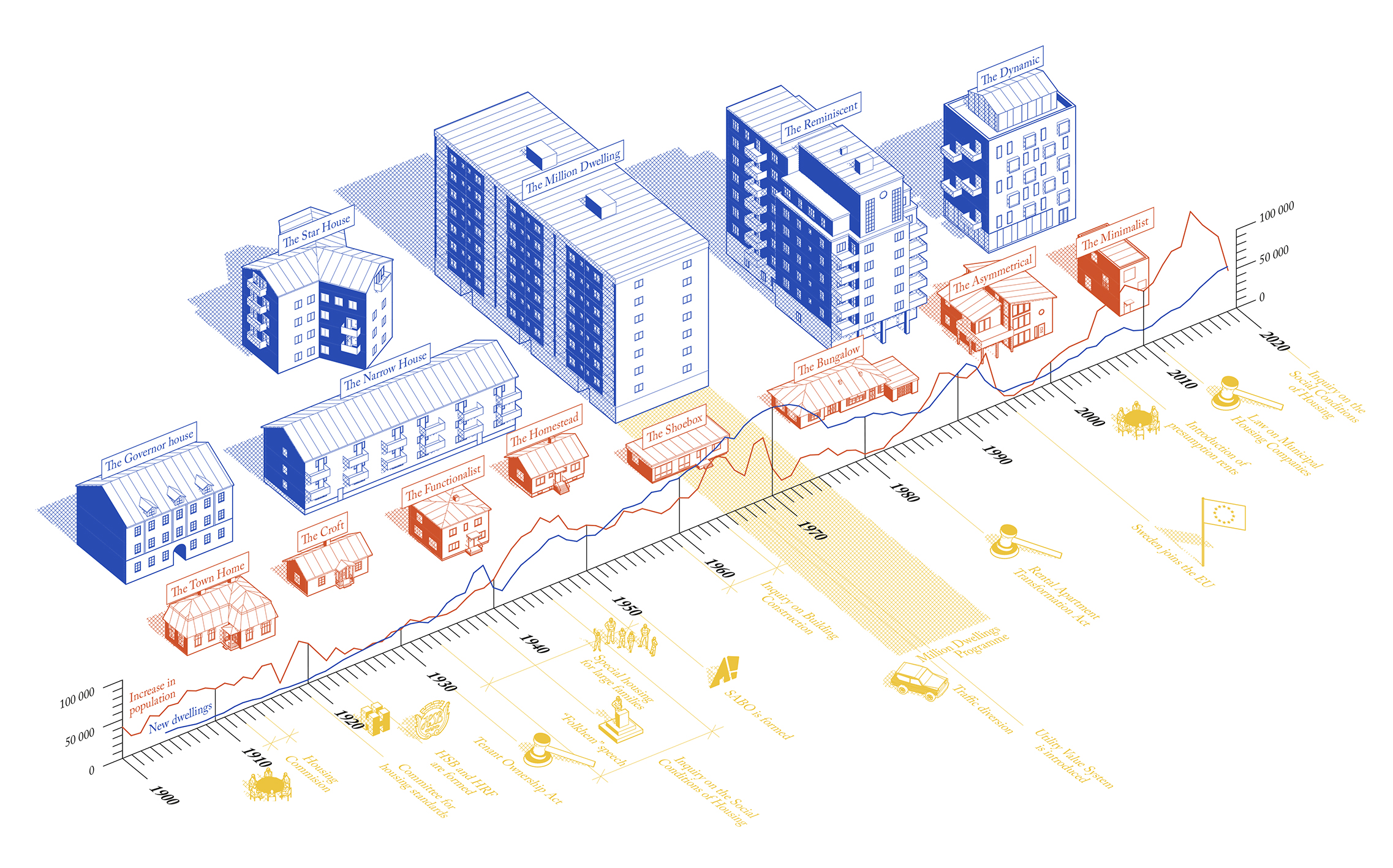

1900 – 1940: Laying Ground for a Housing Regime

One early example of state initiatives geared towards the issue of housing took place in 1904. In order to curb the depopulation of the countryside and the emigration to America, state loans were granted for the construction of housing in rural areas (Hedman, 2008). In 1907 the first ever law that regulates the relation between landlord and tenant was passed. However, the rights of the tenant were still few, and the law mostly helped the tenant terminate the rental agreement if there were issues hazardous to the heath of the tenant (SABO, 2011).

During the first world war the parliament approved a law meant to counteract rent increase. This was later abolished during the recession that followed the war, with sharp rent increases and evictions as effects. This led to the formation of tenant unions like Hyresgästföreningen (“the Tenants’ Association”) and HSB (“the Savings and Construction Association of the Tenants”) (Hedman, 2008).

It wasn’t until the 1930s that political steps were taken to find more permanent solutions to the housing issue. The Inquiry on the Social Conditions of Housing was appointed in 1933, and at the same time new subsidies and loans for housing production were approved. One of the first results of the Housing Inquiry was the so called ”large-family-blocks”. State loans were given to municipalities in order to build housing specifically for poorer families with at least three children. These families were then granted family allowance based on their rent expenses and number of children. This type of housing continued to be built up until 1948. The municipal companies that were established during this time laid the foundation for what would later become the universal public housing regime (SABO, 2011).

In 1942 the second world war had, just like the first, led to a housing shortage as construction and interest rates rose. The state therefore approved loans for both private and municipal housing construction, as well as a law on rent control and tenancy rights. Along with the terms for construction loans the public housing companies were further defined as non-profit organisations. The rent control was structured in such a way that the loans for construction were conditioned on the fact that the rent for the produced flats could not exceed the rent levels of 1939. Through these measures the state took the economic risks of construction while gaining additional control over the housing market (SABO, 2011).

1940 – 1970: Growth by Good Housing for All

In December 1945 the Inquiry on the Social Conditions of Housing presented their main findings, which came to shape the Swedish housing regime in a number of ways. Perhaps most important was the idea of a universal housing policy which did not target specific vulnerable groups. The ”large-family-block” policy, which did just that, had been criticised for stigmatisation and was abolished in favour of a new program for housing production. Targeted support to vulnerable groups were to be given through cash support instead of specialised buildings. The new program included private and cooperative construction but favoured the municipal public housing companies. The goal was to achieve good housing for all, a consistent production of housing with low rent levels, as well as to counteract speculation. Housing costs were not to exceed 20 % of the gross household income and renovations increasing the housing standard should not affect the rent (Grander, 2018). The number of public housing companies rose quickly, and in 1950 the organisation SABO (later Public Housing Sweden) was created in order to represent the interests of these companies (SABO, 2011).

The goal was to achieve good housing for all, a consistent production of housing with low rent levels, as well as to counteract speculation.

Worth noting is that the housing policy was during this time regarded not only as an instrument of housing supply, but also as an important instrument for economic growth and stability. Sufficient housing was needed to expand the manufacturing and export industry, while capital and labour force could not be too tied up in the construction industry. Regardless of the state’s calculations on the long-term needs of construction, the housing shortage grew steadily with the increasing nativity and domestic as well as international labour immigration. By 1959 the situation had grown untenable, and the parliament appointed an inquiry on housing construction. Its findings and propositions were presented in 1964 and implemented the year after and became what we know today as the Million Dwellings Programme (Hedman, 2008).

The Million Dwellings Programme meant that the government guaranteed to help sustain the annual construction of 100 000 dwellings per year over a ten-year period. This rate of construction was already almost fulfilled, with almost 90 000 dwellings built in 1964, but had to be maintained in order to meet the high demand on housing created in part by the expanding manufacturing industry. From 1965 to 1974 just over one million new homes were built, most of them in apartment blocks and by the public housing companies. It was through this project that the municipal public housing companies came to manage a majority of the apartments in Sweden (Hedman, 2008).

The tenant owned housing had until now been seen as a key player in the public housing provision and the transfer pricing was under strict control. However, this role had gradually got lost and in 1968 the regulations on transfer pricing were abolished. Some feared this would lead to a divide in who chose which type of tenure, resulting in tenant owned housing being more attractive to those who could afford it. When market prices were applied to tenant owned apartments the rate of construction of them rose (Grander, 2018)

1970 – 1990: Interest Deductions Fuel Segregation

By the early 1970s the housing shortage seemed to be over and suddenly there were more empty flats available than demand called for. The construction of multi-dwelling buildings decelerated while the demand and production of single-family houses rose. A favourable taxation plan meant homeowners were able to deduct all of their interest rate costs from their income taxation. Those who could started to move out from the large apartment blocks while refugees of increasing amount were referred to move in. This led to a situation where an increasingly disproportionate share of tenants in these areas was comprised of vulnerable groups – the very kind of class segregation which the universal housing policy had set out to counteract. Even before the decade of ambitious housing projects had come to an end its produce was harshly criticised. The municipal housing companies which hitherto had been focused on high construction rates now had to adapt to the new task of managing a large number of dwellings (Hedman, 2008).

Since the municipal housing companies had relied heavily on state loans, they had a very limited capital reserve. This proved to be a problem when vacant flats entailed losses in rent income and the need of refurbishing in the old housing stock rose (Hedman, 2008). In 1982 a new law allowed rental apartments to be converted into tenant owned as long as at least two thirds of tenants agreed. This became a way for municipal housing companies to rid of the apartment surplus while at the same time gaining capital for the management of the retained stock. Over 20 000 municipally owned apartments were sold during the 1980s (SABO, 2011).

1990 – 2000: Marketisation of Housing

The first years of the 1990s saw both the burst of the housing bubble as well as big changes to the national housing policy. From here on began a back and forth between left and right governments as well as between state support and liberalisation, yet with an overall trend of the latter. In 1992 the state subsidies for construction were dismantled and the possibilities of state support for public housing companies were levelled to those for private companies. The financial risk of construction was moved from the state onto market actors, while changes in the housing policy meant municipalities were no longer obliged to provide housing to its inhabitants in the same way as before. This meant there were no longer any laws or regulations in place which defined the role of the public housing companies. The public housing companies now by necessity started to compete on the market in a way that they previously had not (SABO, 2011). Most who had been run as foundations were now reformed into limited companies, which let municipalities more freely use dividends for other municipal ends. Many municipal housing companies started to sell out their housing stock (Hedman, 2008).

Since the government deemed it necessary that the public housing stock still was substantial enough to act as comparison within the use-value rent setting system they took different measures to prohibit this trend. First in 1994 by withdrawing the interest rate subsidies of the companies that sold out stock. Later, in 1999, the state passed a law which made it possible to decrease the general subsidies to municipalities which sold their public housing stock. This law proved effective, but was abolished in 2002, when municipalities instead had to seek permission from the county administrative board in order to sell (SABO, 2011). This happened in conjunction with the passing of the first ever separate act on non-profit housing companies, thereby reintroducing a definition of what they were. The terms were that the company mainly dealt with the management of rental apartment buildings and had to be run as a not-for-profit organisation. This meant that other companies than those owned by municipalities could be authorised. However, since there are currently no benefits to gaining that authorisation that novelty has come with little effects. In 2007 the permission obligation for the sale of municipal public housing was abolished (Hedman, 2008).

By this time housing had come to be an income instead of an expense for the state. In the late eighties housing imposed a net cost of around 30 billion per year. In late nineties it instead delivered a net income of about as much (Christophers, 2013).

2000 – 2020: Global Financialisation of Housing

With the arrival of the new millennium a new player entered the Swedish housing market: the international finance companies. Their business idea often consists of buying old public housing estates and then renovating them in a way that increase the rents substantially, thereby forcing less affluent tenants to move out. This is often referred to as “renovictions” (Gertten, 2019). The possible financial gains can in fact be argued to be greater than for traditional assets, which leads to large financial actors outbidding smaller housing companies in buying low-rent apartments (Grander, 2018).

Since 1995, when Sweden joined the European Union, there had been discussions about how well the national public housing policy complied with the EU competition laws. In 2005 a commission of inquiry was appointed to review what changes might be needed to be made to the municipal housing sector (Hedman, 2008). Its findings shaped the new regulations for municipal housing companies which came into effect in 2011, albeit with great impact from a joint counterproposal by SABO and the tenant union (Grander, 2018). The law specified the housing providing role of the municipal housing companies but also established that they had to act in a business-like manner with normal rates of return. The law also made clear that the municipalities no longer could use the municipal public housing companies to meet the housing demand, since they no longer were allowed to allocate resources in a way that would benefit the public housing companies on the free market. The municipality could no longer demand action from its own company (Hedman, 2008).

Following the change in legislation in 2011, municipal housing companies have applied stricter rules for getting a rental contract. Among other things the level of household income is now required to be higher than before, while temporary income, housing allowance and social benefits no longer qualifies as legitimate income (Grander, 2018).

The adaptation of public housing conditions to EU rules has been questioned by scholars, claiming that a rigorous lobbying made leading politicians believe that it is not possible to have political housing goals within the EU legislation. This however is not necessarily true. Some argue that the European Court of Justice does not have jurisdiction within national housing politics. This would mean that there are no restraints for the state to fund an expansion of the public housing stock other than those adopted by itself (Byggnads, 2019).

In order to make rental apartments a more attractive alternative for construction, a system of presumption rents was adopted in 2006. This basically meant that new rental construction could bypass the utility value system and assign rents based on cost coverage and reasonable return. While this may have increased the construction quantity of rental apartments the rents have become unaffordable to average wage and salary workers (Bostad 2030, 2018).

The introduction of presumption rents should be regarded ‘beyond’ market-based rents as it completely takes away the risk for the constructor.

Grander, 2018

2020 – : A Political Dilemma?

It can be said that there has been a shift from national housing politics to local ones, which in turn makes the situation very different depending on where in the country you live. Municipal housing companies are expected to act in a business-like manner with normal rates of return yet strive to achieve societal benefits. The reduced opportunities for municipal financial support, along with the increasing housing shortage and demands of business-like management, has forced some municipal housing companies to sell parts of their housing stock in order to secure economical means for construction. Since a common calculation means the sale of two dwellings in order to produce one new, this lessens the municipal share of housing (Grander, 2018).

In May 2020 the government once again appointed an inquiry on the social conditions of housing (Dir 2020:53). The directive includes two main areas; the division of tasks between state and municipality and the political tools for aiding those with weak positions on the housing market. It specifically asks for an analysis of the conditions for the non-speculative housing market and how that part of the housing market in Sweden can increase.

While this can seem like the government is strengthening their positions regarding affordable housing, this directive came just two weeks after they appointed an inquiry on unrestrained rent-setting on new production of housing, commonly referred to as market rents (Dir. 2020:42). This despite the fact that 70 % of all voters seem to be against market rents (Hem och hyra, 2018).

While affordable rental dwellings seem like the most obvious way of securing good housing for households of all income levels, some mean that a solution to the affordability crisis could instead be solved by reducing the cash- and amortisation requirements on bank loans. However, that would contradict the goal of the government, the financial supervisory authority and the state bank, as well as IMF and OECD, to retain the level of debt of the households. The debt of Swedish households has increased dramatically since the mid-nineties and now accounts for the internationally high level of 180 percent of the disposable income (Bostad 2030, 2018).

Christophers (2013) identified three remaining areas of regulation; rent regulation, queueing systems for rental apartments and restrictions on apartment letting and sub-letting. At least the first two are now being challenged through market rent inquiries and a trend among private landlords to leave the housing queues. The need for the state to once again take on a national responsibility for adequate housing is underlined by researchers (Bostad 2030, 2018). The market forces, more specifically the banks, real estate companies and homeowners, all share an interest for maintaining the high market value of the existing stock and will not be a driving force for solving the housing crisis.

Today, housing is the single biggest financial asset in most economies as well as personal asset for a large share of the population. Thereby housing distinctly affects the way people vote. The Swedish housing system has been applauded in the international leftist narrative and continues to play a cathartic role in the discussion of housing. At the same time the Swedish housing market is being described as increasingly liberal and market oriented. The Swedish housing regime has become a hybrid, consisting of both regulated and marketised factors (Christophers, 2013).

It is clear that the situation on the Swedish housing market is regarded problematic by both voters and politicians, but there is no single popular idea of how to solve it. While searching for a solution the existing mechanisms continue to effect social and economic inequalities in a number of ways, which will be explored in the following chapters.