What we build is not what we need

Low Level of Construction

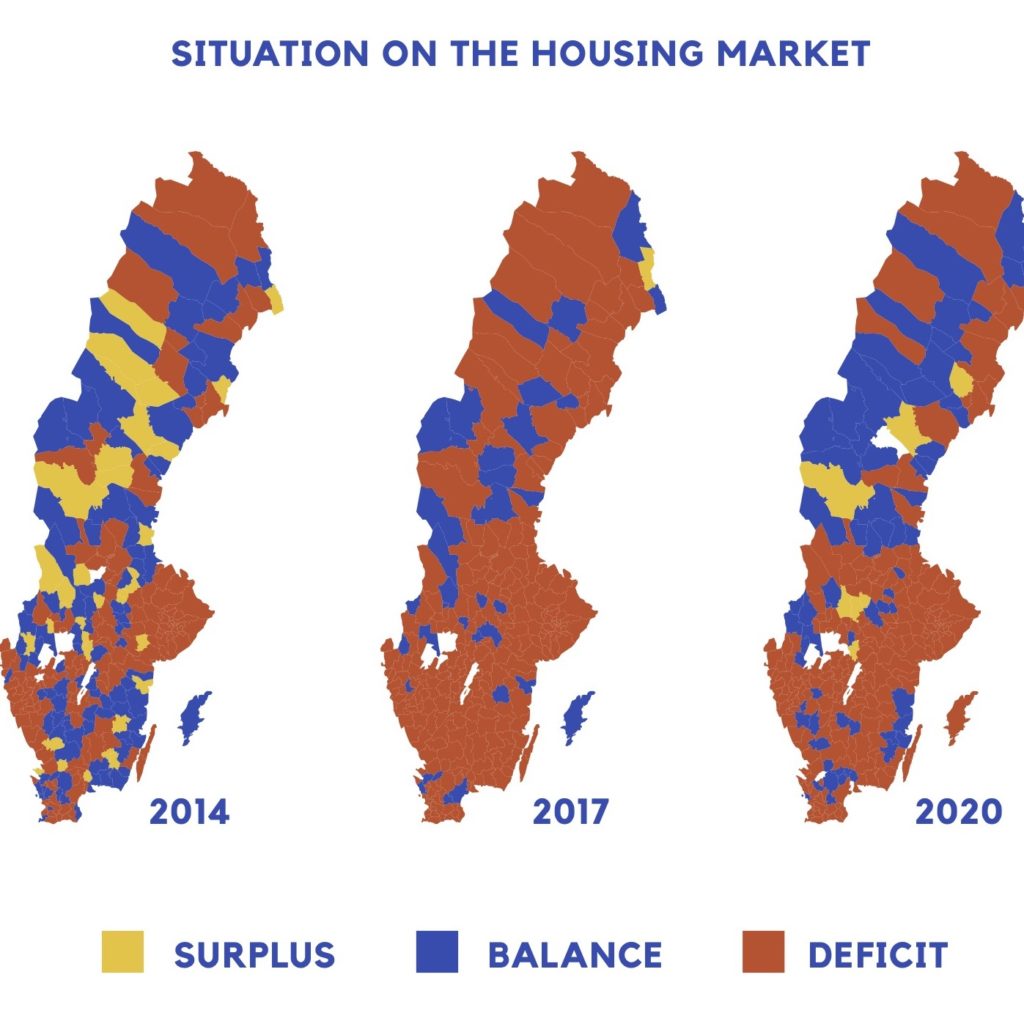

The current housing shortage cannot be tackled in an instant. The rate of construction must both meet the growing population as well as the accumulated dwelling deficit. The housing deficit grew steadily from 2006 through 2017, after which it has been somewhat shrinking (Boverket, 2020b). The Swedish National Board of Housing, Building and Planning estimates that between 59 and 66 thousand dwellings must be built annually during years 2020 through 2029 in order to meet both population development and the accumulated housing deficit (Boverket, 2020a). That is a level of construction that has not been met since 1992. About 70 % of the construction needs to happen in the three large city regions (Boverket, 2020b).

Construction companies claim that the housing shortage is due to high taxes and strict regulations. Perhaps not an unexpected argument from those who seek to make money from housing construction. But would lower taxes and looser regulations really result in the production of more affordable housing? A more probable scenario would be that lower costs for production would allow construction companies to raise their profits. After all, regulations have systematically been phased out since the early nineties and the result has not been more affordable dwellings but rather the opposite (CRUSH, 2016).

Some believe the adoption of market rents would increase the level of construction of rental apartments. This can be claimed to be disproved since the presumption rent system is in fact very close to a market-based rent setting system for new production (Bostad 2030, 2018). Hence, market rents would probably not affect the level of construction and most certainly would not engender more affordable dwellings.

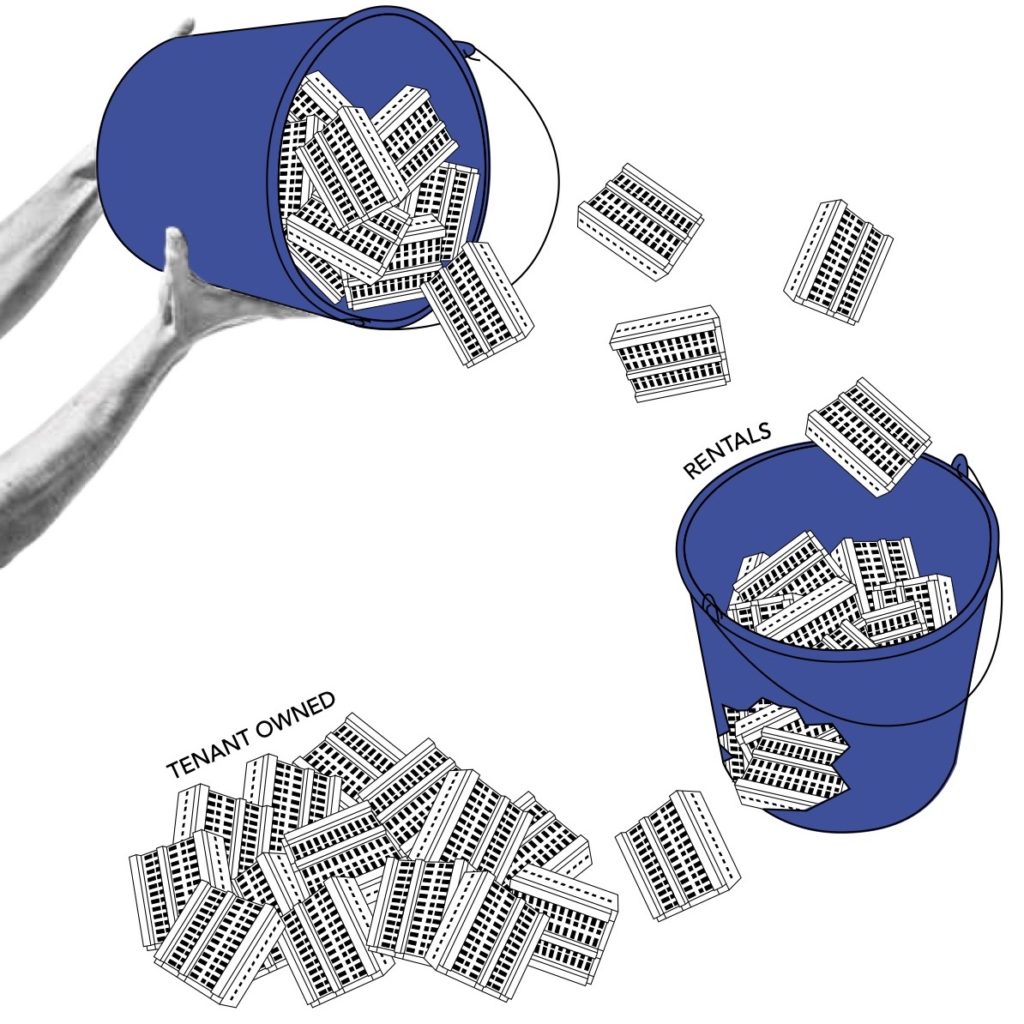

Pouring Into a Leaking Bucket

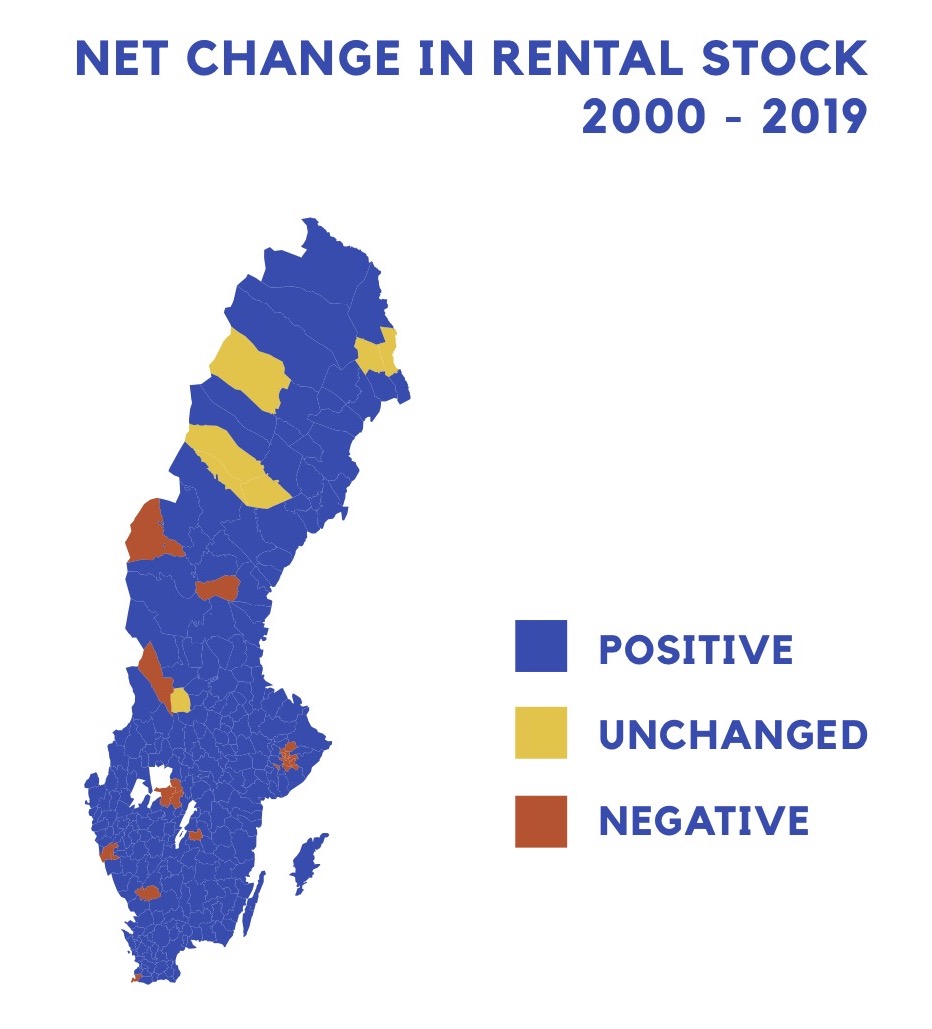

Regardless of new construction, the rental stock barely increased during the last 20 years, in part due to transformations from rental to tenant owned apartments. The conversion from municipal rental to tenant owned apartment often lets tenants buy their apartment well below the market prize, resulting in billions of tax money ending up in the pockets of the new owners (Christophers, 2013). Transformations take apartments off the rental market. Despite all new production of rentals, the national rental stock in 2018 was at the same level as in 2000 (hurvibor.se, 2020). This situation is even more pressing in the large cities, where rental stock has in fact decreased dramatically.

Transformation vs. production of rentals in Stockholm

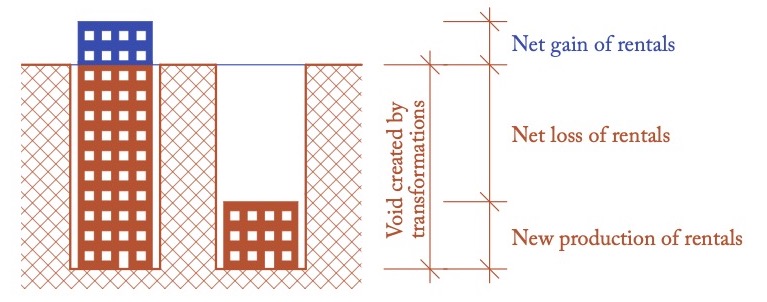

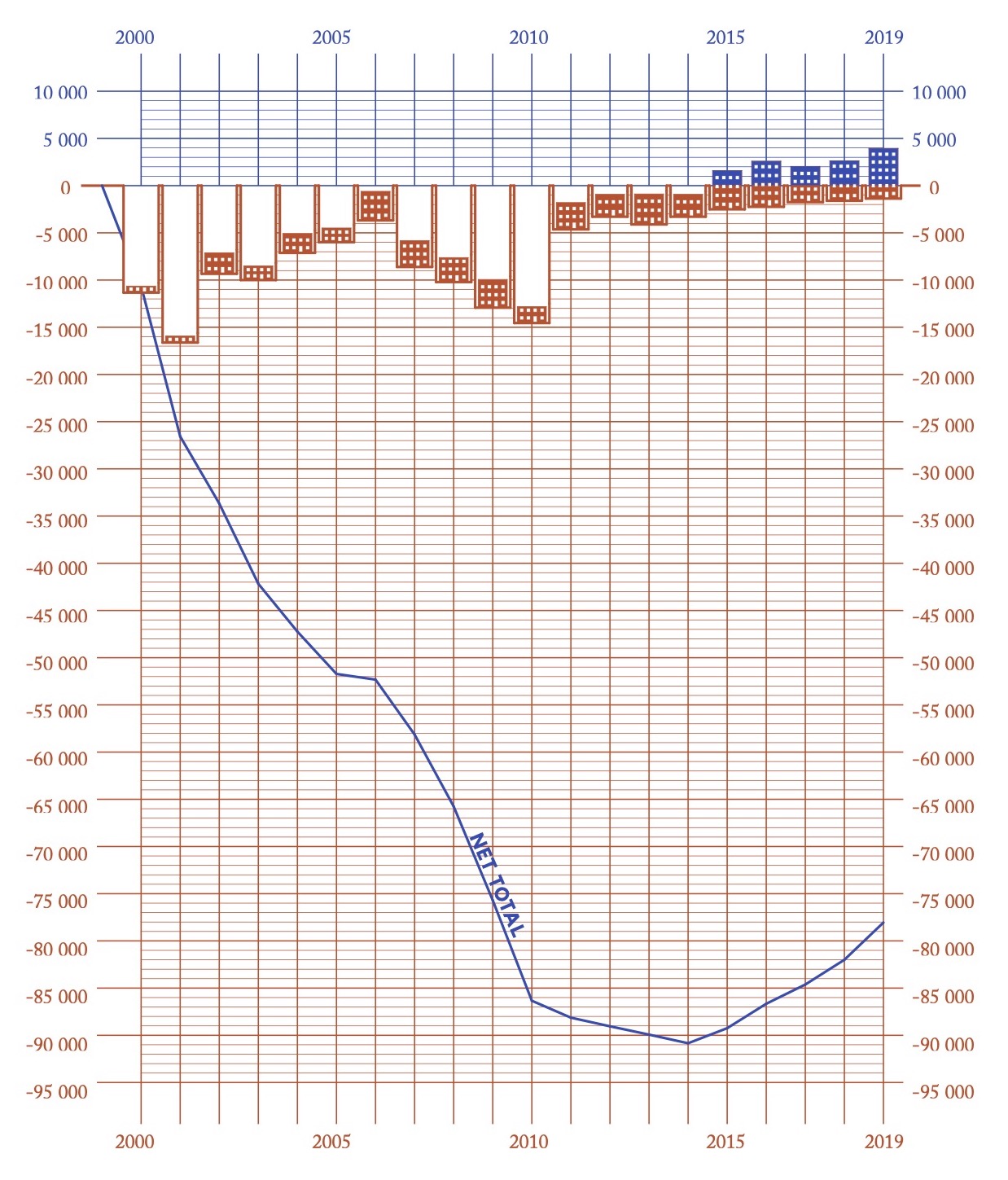

The rental stock has increased in most parts of the country, while transformations are mostly an issue of metropolitan regions. Let us look at Stockholm as an example, where the transformation of rental to tenant owned housing is creating voids in the existing rental stock. The level of new production of rentals in Stockholm county has for the majority of the last twenty years not been high enough to fill those voids, much less increase the existing stock. The total rental stock is thereby significantly smaller than what it was twenty years ago – a debt that new construction only just started to pay back. Only during the last five years has the production of new rental dwellings exceeded the number of transformations, thereby adding a positive number to the existing stock.

The positive trend is likely to be tied to the ban on transformations that the local government put on the public housing companies in 2014 (Svenska Bostäder AB, 2014). This had been done in steps since 2008, when transformations in the inner city and some central suburbs were stopped. The large number of transformations already in motion postponed the effects of the ban until 2011, from when transformations only were allowed in areas where rentals were the predominant tenure type (Svenska Bostäder AB, 2014). In 2019 however, transformations were once again offered in outer suburbs where at least 60 % of the stock were comprised of rentals and where the public housing companies owned at least half of them (Svenska Bostäder AB, 2019). The effects of this recent change are still to be discovered. In 2019 there were still 78 000 less rental apartments in Stockholm county than there were in the year of 2000. Over the same period of time the population of the same region has grown by over half a million.

Shifting Regulations

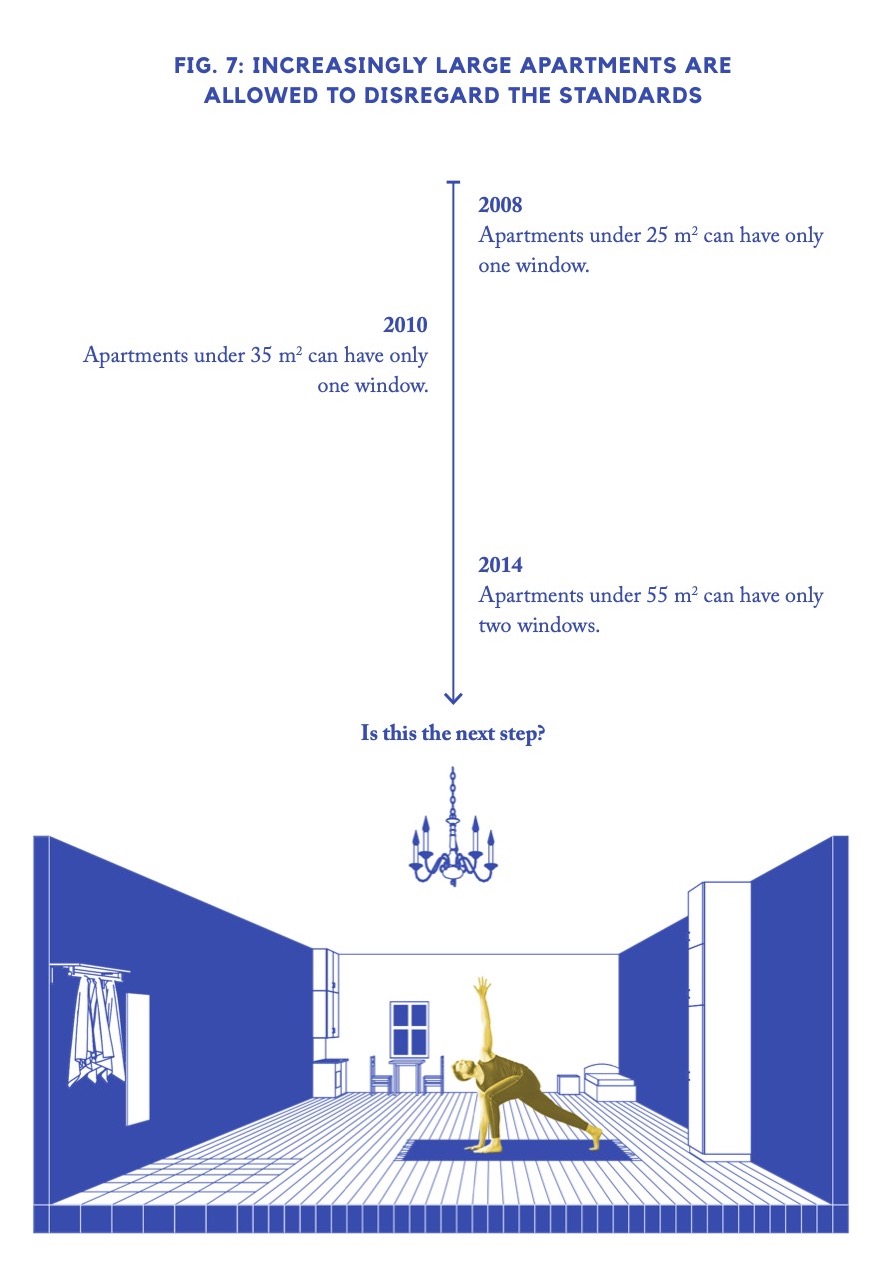

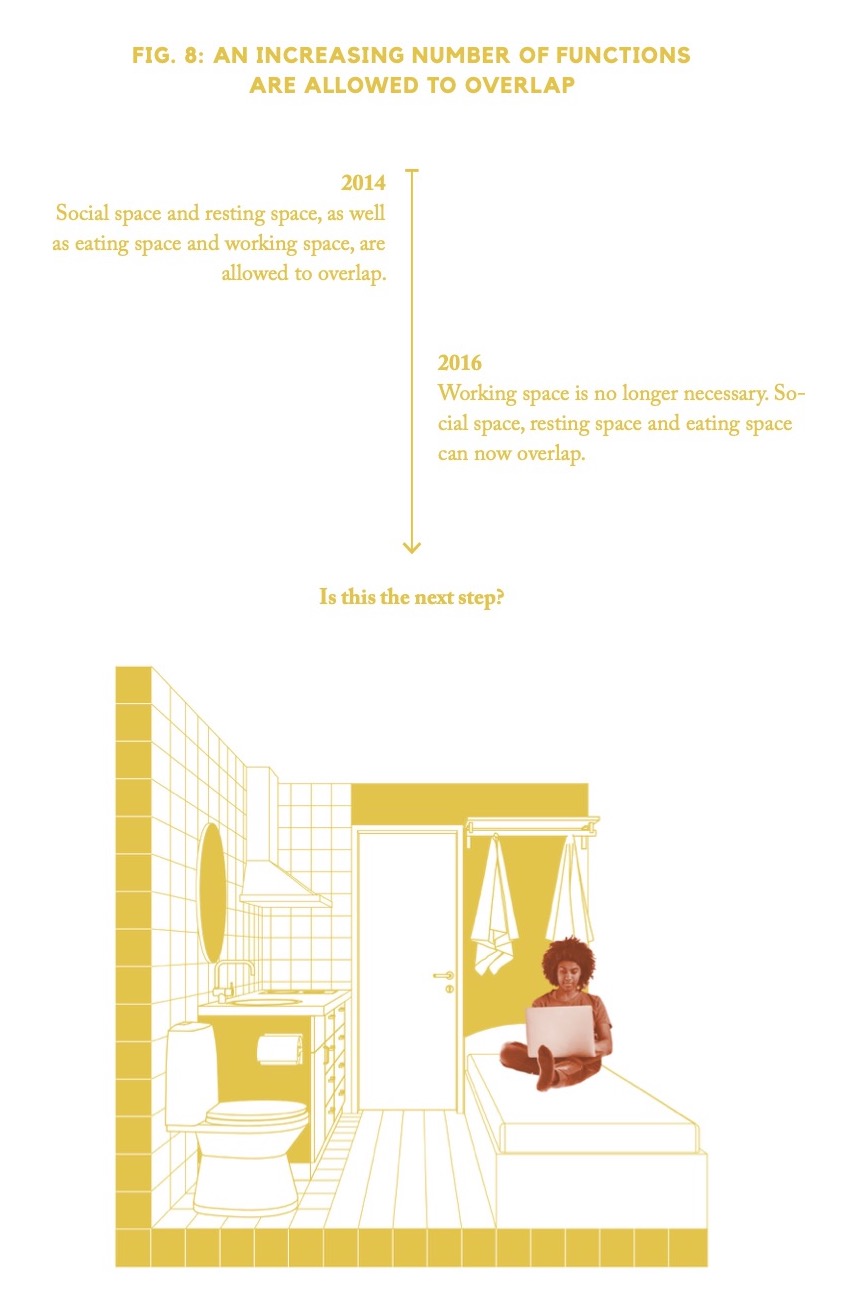

Sweden has implemented quite strict regulations for the lowest acceptable standard of a dwelling. Some are critical towards this approach and claim that they are in part responsible for both the low construction rate and the high production prices (Siljevall, 2019). However, lowering regulations for dwellings has in fact already been done in steps.

In 2014 new rules for student housing and small apartments were adopted. Dwellings were allowed to be smaller, darker, noisier and have less storage and hygiene spaces as well as less ventilation (CRUSH, 2021). These changes did not necessarily lower the price per square meter but could lead to lower actual rent since the apartments were allowed to be smaller than before. These new small dwellings with lower standards permanently add an increased overcrowding in the housing stock, which will end up affecting some groups more than others. The small typology is most of the time also located to specific geographical areas, which amplifies patterns of segregation. It is critical that we maintain a high standard of housing, since dwellings of lower standards would dominantly affect low-income households who already struggle to find adequate housing Since the days of the million dwellings programme the collective aim has been to strive for varied housing areas where dwellings of different sizes and tenures are mixed. This current tendency to question the high standards contradicts that aim and could lead to increased segregation and stigmatisation (CRUSH, 2016).

The question is if the change in regulations has in fact lead to the effects we have hoped for – like a higher level of production and more affordable rental housing – or if the main effect is just the actual change in size and design. How far can we push deviations from the regulations meant to secure adequate housing standards before it gets irrational? The balance point between production costs and appropriate standards is not obvious. Where will we end up if we keep pushing for lower standards?