Who we are determines how we reside

Housing Equality

The research field of housing equality has grown during the last couple of years, and there are numerous recent publications addressing the issue. Housing equality builds on the notion that housing should not be a factor which determines one’s possibilities in life. To discuss housing inequality is a way of combining the understanding of a number of social aspects of housing distribution. In short, it is about the difference in housing opportunities between different social groups. Its effects are less affordable, less secure and less decent housing. A proposed categorisation of housing inequality is to distinguish between access to and quality of housing (Grander, 2018).

For example, young adults have an increasingly hard time entering the housing market. Solely their age restricts them from having sufficient time in the housing queues and often they have unstable incomes and limited savings. Not being able to find a home of their own they have to keep living with their parents, which postpones their transition to adulthood. Living in crowded conditions can also make it difficult to study and find employment, which in turn are factors proven to be of importance in terms of health and life expectancy. These mechanisms illustrate how housing inequality reproduce other inequalities in terms of financial resources, existential matters and health and well-being (Grander, 2018).

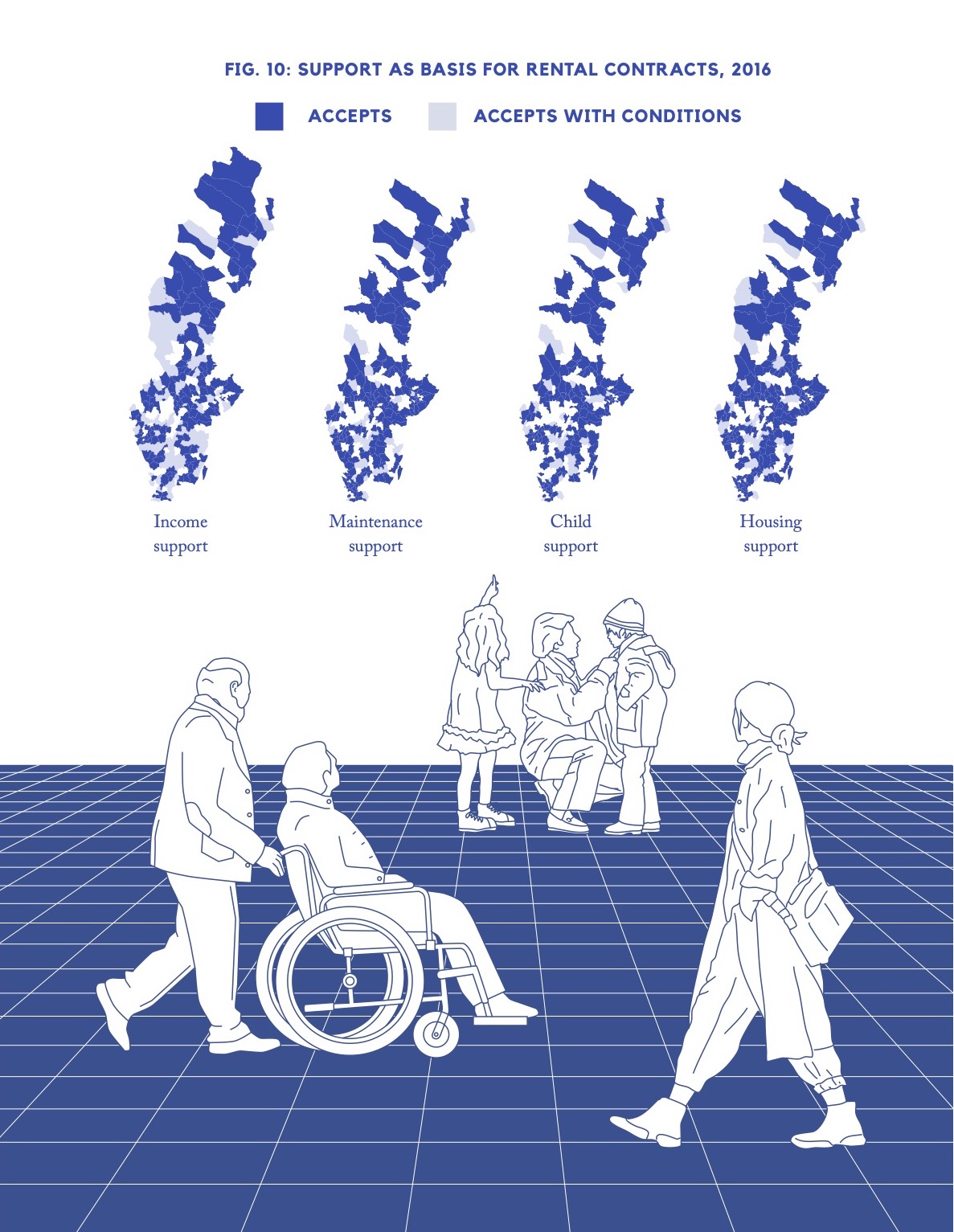

The support systems meant to aid those who struggle economically sometimes fall short of helping when it comes to secure a rental contract. Many both private and municipal landlords do not accept social benefits as an income basis for rental contracts (see Fig. 10) (Hem och Hyra, 2016). If these landlords do not accept social benefits as a secure income, the remaining municipal housing companies seem to be alone in catering for these vulnerable groups. This means landlords no longer are competing over the same tenants, causing a divide between public and private housing, which in turn becomes a threat to the universal housing system (Grander, 2018)

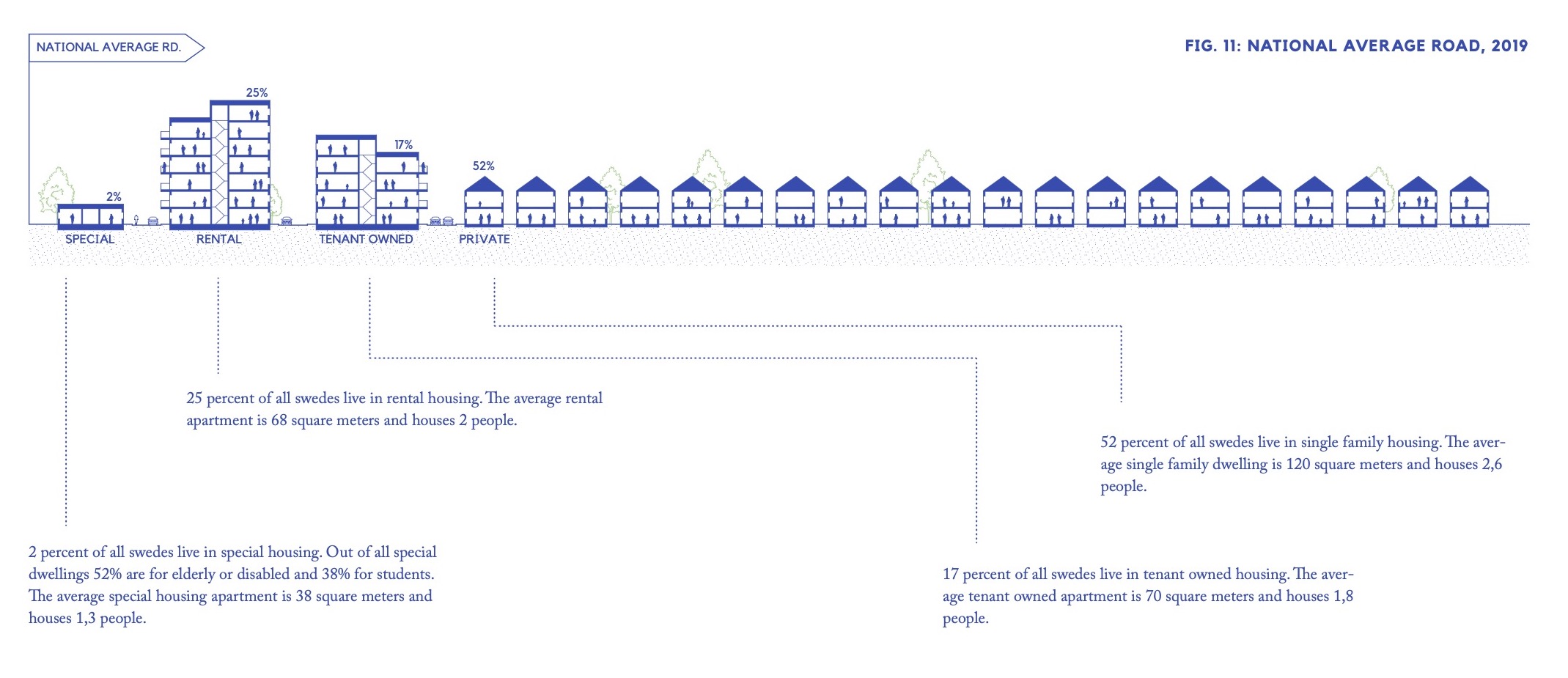

The following street sections are based on how a population of one hundred individuals statistically spread across the different tenures. If one hundred people from a certain group would live on the same street, what would that street look like? The missing percent account for people who are not registered on any address. The average sizes of dwellings are calculated by the average living area per capita for each tenure type multiplied by the average number of individuals residing in an apartment of the same kind.

Segregation

The current housing crisis is said to have been accelerated by the large number of immigrants arriving in Sweden in 2015 – in fact the largest number since the Second World War (Grander, 2018). A common myth is that segregation is due to immigrants wanting to live close to others of the same heritage; that they choose to group themselves. It only takes a recollection of the limited room for manoeuvre for vulnerable groups to realise that is not true. If any group is to be blamed for segregation it is those who have the resources to opt out of certain housing areas, those who have the privilege to really choose where they want to live. Patterns of this kind are sometimes referred to as “white flight” or “white avoidance”, meaning that Caucasian individuals choose to move out of, or not move into, certain areas. Thereby it is the affluent part of the population who amplify the housing segregation, not the other way around (Formas, 2011).

However, the real responsibility of segregation cannot be assigned to individuals but should rather be seen as the result of political policy. As previously described, policies for state loans have previously prohibited housing projects with mixed tenancy types. Since different types of tenure have been proven to attract different tenants, this mechanism has created an almost permanent segregation within the housing stock (CRUSH, 2016).

Housing is more expensive for those with foreign background. Their average relative housing expense is higher than those without foreign background. They are also more likely not to be able to secure basic consumption needs (Boverket, 2016). Studies also show an incremental change in who chooses to reside in public housing apartments. A process of residualisation – meaning that those who have to possibility choose to move out – leaves an increasingly large share of less affluent households residing in public housing dwellings (Grander, 2018). This trend is in stark contrast to the well-established resistance towards social housing. If the public housing companies end up catering to vulnerable groups only, then arguments against social housing based on avoiding stigmatisation fall rather flat.

Facilitated Settlement in Other Municipality

The current imbalance on the housing market has led to several unwanted phenomena. One of them is that individuals who are dependent on social support are helped to move to another municipality. This is sometimes called ‘social dumping’ or ‘social export’. However, since these expressions have been criticised for being derogatory and stigmatising it is increasingly referred to by authorities as ‘facilitated settlement in other municipality’ (author’s translation, Statskontoret, 2020:19).

Studies show that it is more common for municipalities with poorer economical and labour market conditions to admit individuals that has been helped by the previous home municipality to move. The most important factor seems to be the varying housing availability, which tend to make socially vulnerable people end up in places where it might be easier to secure housing while it may be harder to find work. Some municipalities even demand that people who seek income support must look for housing outside of their home municipality. Facilitated settlement in other municipality mainly hits immigrants, individuals with drug abuse or other social issues, structurally homeless and individuals in need of protected residence (Statskontoret, 2020:19).

This kind of movement risk that those affected will end up in an even more permanent need of support, as they might end up where it is difficult for them to find a job and secure self-sufficiency. Since the goal of social services is that individuals reach self-sufficiency as soon as possible this becomes a conflicting mechanism. Vulnerable individuals are put in a position where they have to choose between housing and work. Receiving municipalities also witness a lack of information exchange from the previous home municipality, which risks duplication of efforts and makes it hard to plan efforts and operations (Statskontoret, 2020:19).

In some cases, initiatives for intermunicipal movement comes from private landlords in municipalities with an excess of rental apartments. While this can seem like a helping hand for those looking for housing, the standard of the offered apartments is sometimes low and the rents paid by social services high (Statskontoret, 2020:19).

Gentrification

Gentrification can be understood as the physical manifestation of class based and ethnic inequality. The term was invented by sociologist Ruth Glass to describe a process where previously “rough” neighbourhoods were taken over by a more affluent clientele, forcing the original inhabitants to move out because of raised costs. This is of course a process that favours those who own real estate in the area, since the estate value of the area tend to multiply. But for those who live in the neighbourhood it can be devastating, as raised costs can force them to move. Research show that households that are forced to move because of raised rents tend to end up with temporary and uncertain housing for long periods of time (CRUSH, 2016).

Renovictions

Closely tied to patterns of gentrification is the process of forced movement following substantial renovations – commonly referred to as renovictions. Large parts of the rental housing stock are in need of renovation, which is emphasised by companies who can use these renovations to argue for a higher utility value and thereby raise the rent of the apartments. Higher rents can force economically vulnerable groups out of their homes and into a long-term insecure housing situation. Tenants in renovated rental homes are almost twice as likely to move out than others and moving is closely tied to the economic situation of the household (Boverket, 2014). The fact that tenants are more likely to move after renovation by a private landlord than by public housing companies points to the fact that the renovations often are means to an economic end for the landlord rather than an improved housing situation for the tenant. Those who move from renovation tend to end up in areas with a lower income average and worse study results, which indicates that renovictions contribute to segregation and social inequality (Boverket, 2014).

The municipal housing companies used to aim for rent income to cover regular maintenance. However, since a ban on setting aside funds for specific maintenance and a taxation on general maintenance funds were introduced during the nineties, this has become tricky. The cost for maintenance now has to be covered by the tenants or by selling other parts of the housing stock (Boverket, 2014).

Research show that renovations are often more extensive than need be, which suggests that the effects of raised rents followed by processes of gentrification can be desired by landlords. Whom are the renovations really meant to serve?

Tenure segmentation

Tenure neutrality used to be a way to make sure political policies did not favour any type of tenure more than the other. The government wanted to make sure no type of tenure would be regarded as better, resulting in stigmatisation or segregation. Since the nineties however, this standpoint has been neglected and replaced by an ideology of home ownership. This new way of looking at tenure transfers the housing responsibility from the state to the individual (Christophers, 2013).

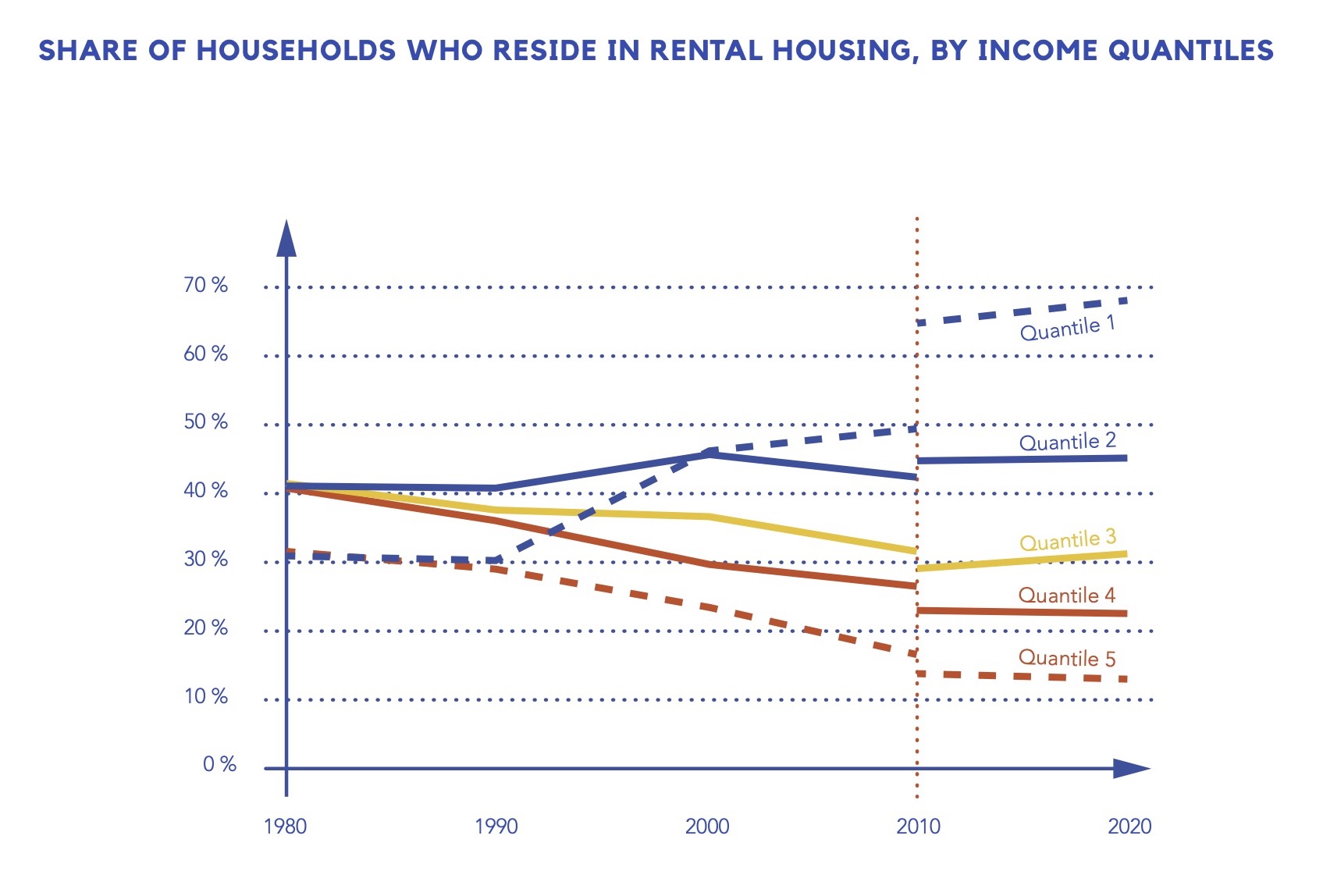

Today, income and tenure type are closely correlated. The higher the income of a household is, the less likely they are to reside in a rental apartment. It has not always been like this. In early eighties the wealthiest and poorest fifths of the population were just as likely to live in rental dwellings, as were the three remaining fifths (see above figure: the break in the diagram marks a change in the data collection, and the outcome of 2010 is included from both. This means that data on the different sides of the mark are not necessarily comparable but can show the upward or downward trends within each set.).

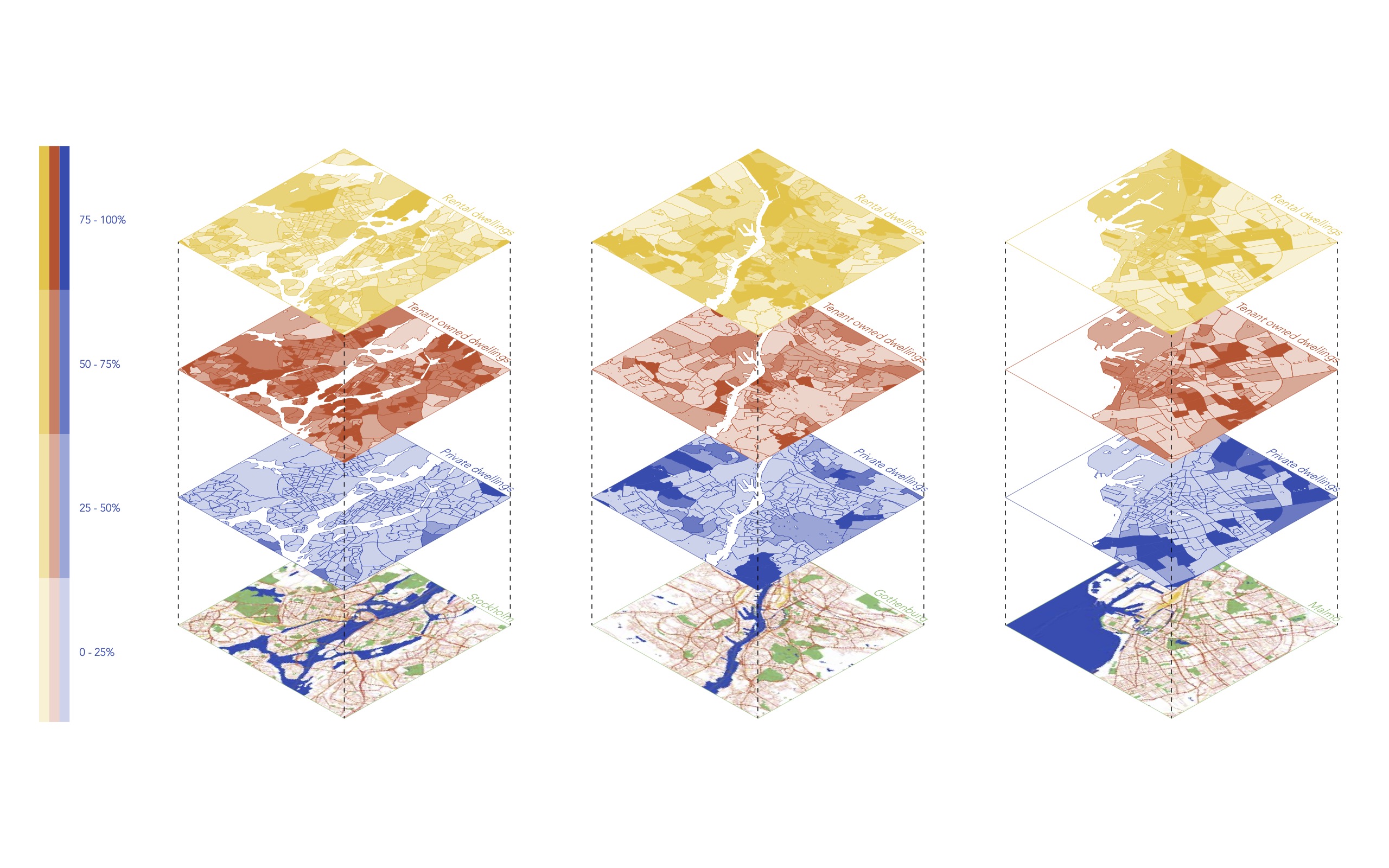

The different types of tenure are more likely to be located in different kinds of conditions. The post-war era of housing construction was marked by the strict separation of tenure types along with traffic separation. Since the interest rate subsidy level was dependant on tenure type a mixture of tenures proved practically impossible. Along with the traffic separation ideal this made Swedish cities become an archipelago of different islands of private villas, cooperative apartment buildings and rental apartment buildings (CRUSH, 2016).

Below you will see exploded views of the three largest cities in Sweden. They are segmented by tenure type and show where which type of tenure is most common. The darker the colour, the more homogeneous the neighbourhood is in terms of tenure. It has been shown that income gaps are most prominent in metropolitan areas (Brevinge, 2016). As seen on the previous spread, income and tenure are closely correlated. This suggests that tenure segmentation on the one hand and income gaps on the other conspire to keep people of different income groups geographically separated from each other.

Information dissymmetry

A pressingly apparent issue is that the housing regime and its mechanisms are hard to comprehend. Complex systems of interacting factors make it hard to understand how to best act within the system. Unequally distributed knowledge of, for example, the housing queues accelerates the inequality on the market. Most people learn about different kinds of tenure and housing from their parents, giving them very different information depending on the parents’ knowledge and personal opinions. Some grow up in homes that are provided by social services and may not have access to information about the primary housing system at all. Information dissymmetry also makes some people vulnerable to exploitation, by not knowing their rights.