How we reside determines who we become

Apart from the obvious ways that our way of residing affects our life, like the feeling of safety, belonging, proximity to nature etcetera, it actually has effects on our identity and economical possibilities.

Territorial Stigmatisation

Previously presented as a cause of housing inequality, segregation can also be seen as an effect of the same. The different social contexts that emerge in different areas affect the health and opportunities of those who reside there, whereby housing plays a great part in the construction of identity. The material and infrastructural resources and the collective social functions of a neighbourhood affect each other. Marginalised neighbourhoods are seen as dangerous and excluded from society. This territorial stigmatisation can be internalised by those living in the area, who in turn experience shame and guilt (Wacquant, 2007). Some of those who reside in stigmatised neighbourhoods see themselves as second class citizens, which in turn affect how they interact with the rest of society (Lindbäck & Sernhede, 2011). Those who experience that territorial stigma limits their opportunities to fair employment might see criminality as their only option.

Housing expands Wealth gaps

During the last decade increasing accounts have stated that there has been a shift from considering housing as a right to considering it a commodity. Scholars do not agree, however, when exactly this change in direction took place. Christophers (2013) argue that it was as early as in 1968, when transfer pricing for tenant owned apartments was deregulated. Others point to the early nineties, when the public housing sector started to go down a more market-oriented path and by that leaving tenure neutrality behind. From there on the rental tenure was seen as a secondary option, only desirable to those who could not afford to buy their home. At the same time changes in the housing allowance policy resulted in a 70 % decline in the number of households entitled to and claiming housing allowance from 1995 to 2009 (Christophers, 2013).

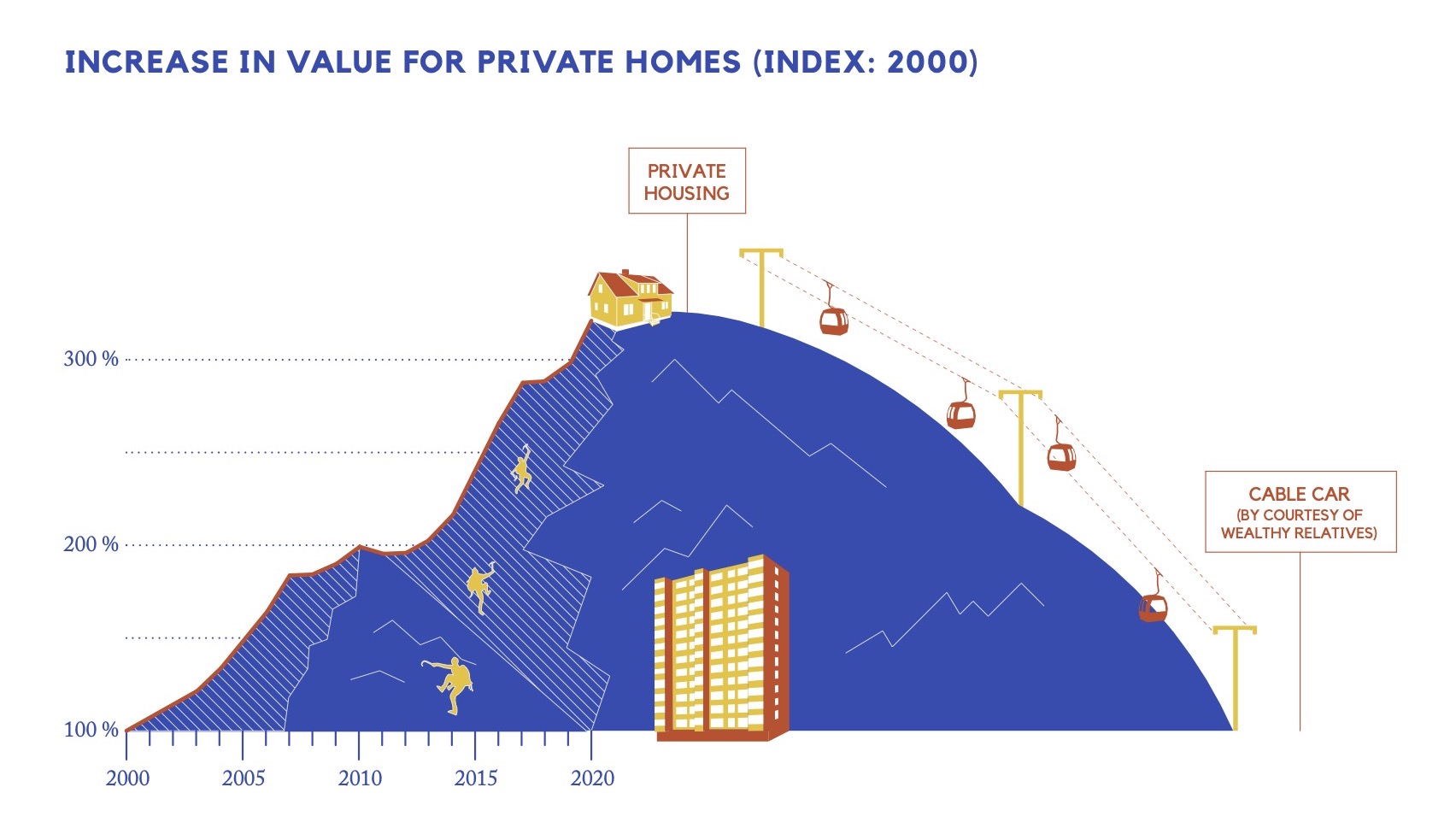

The price for private housing has increased to more than 300 % of what it was in the year 2000. This has become an increasingly high mountain to climb for those who do not already own a home and thus do not accumulate wealth in the same pace. The accessible route to buying a home is now dependant on having a relative whose private wealth has grown enough to be able to help others in the family. They can then give less affluent family members access to an easier route uphill, like a cable car up the mountain of private housing.

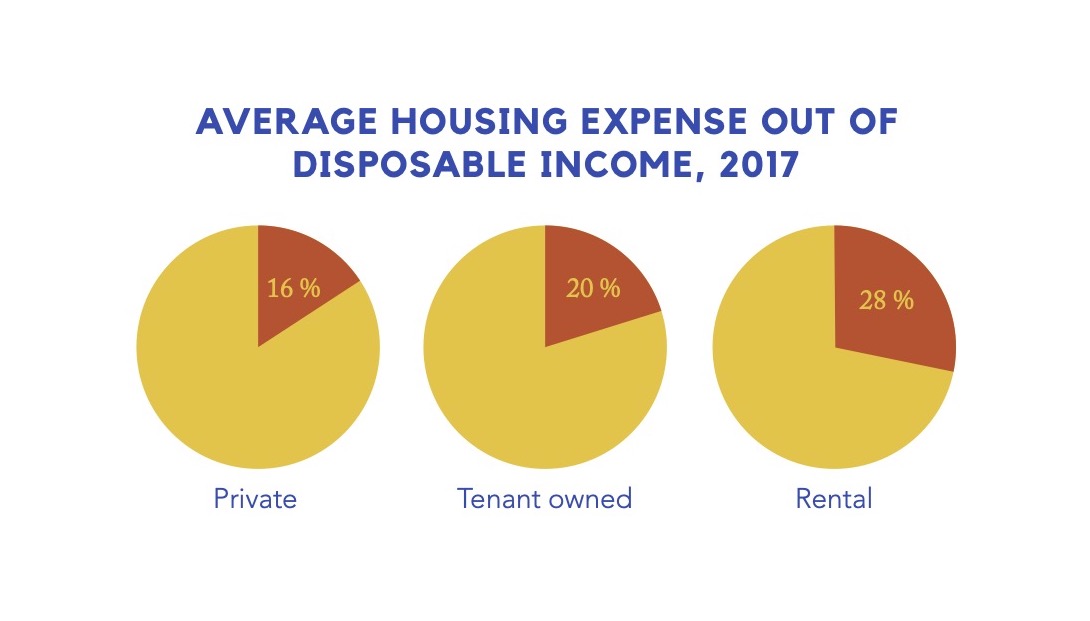

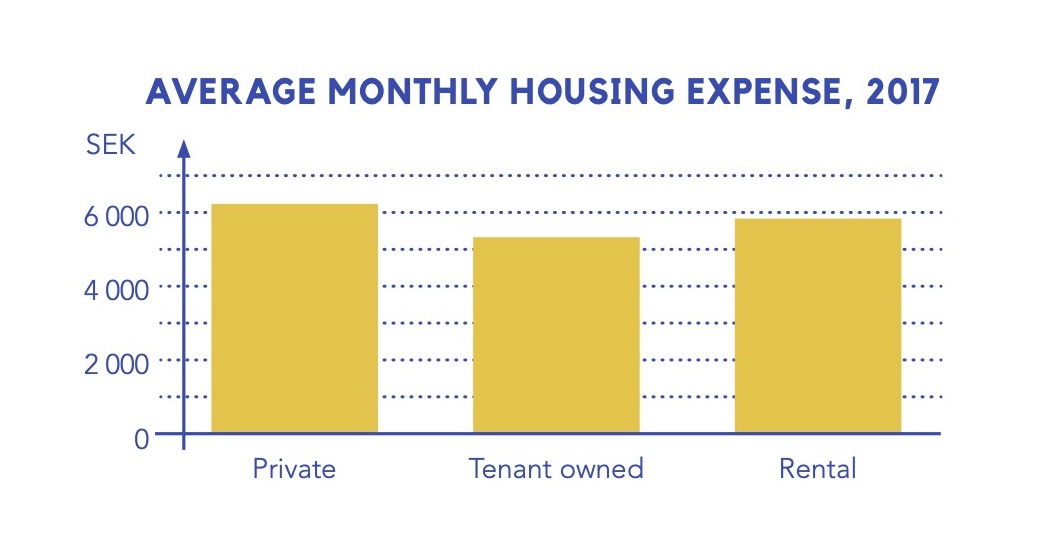

Not only does the rental home typology exclude its tenants from the wealth accumulation that homeowners have benefited, but it is also more expensive. In fact, some studies show that the average cost of a rental apartment is up to about 3000 SEK higher per month than of an equivalent owned one (Grander, 2018). Looking at the population as a whole, disposable incomes have increased more than housing expenses. However, this average is heavily affected by the income increase of the wealthier share of the population. Households with lower income levels experience a different development where basic consumption is hard to manage due to high relative housing expenses (Boverket, 2016).

The housing expense differs between the different types of tenure. Those who live in rental apartments dedicate a significantly larger share of their income to housing costs (note that the above figure shows the expenses for those with a first-hand contract – those with second-hand contracts pay even more). This is in part explained by the fact that those residing in rental dwellings tend to have a lower income, like we explored in the previous chapter. But the average monthly rental expense is also in fact higher than that of a tenant owned dwelling, with monthly charge, interest and amortisation included (see below figure – again, only first-hand rentals are included).

The different types of tenure, in their current configuration, create conflicting interests which enforce the growing inequalities in society, and the housing situation plays an important role in consolidating wealth gaps across generations.

Owned housing has been politically favoured through the introduction of very favourable tax deductions for amortisation, the ability to postpone tax on capital gain through reinvestment, abolition of wealth tax and caps on property taxation. At the same time the taxation of rental property has increased and subsidies for building rental housing have shrunk. This had led to an altered composition of tenure types in the housing stock. Rental apartments, which used to be the most common tenure type, are increasingly marginalised on the Swedish housing market. Property- and homeowners as well as lending institutions rely on rising housing prices, which would be threatened by a sufficient supply of housing. With first-hand rental contracts being harder to come by, large groups of people are forced to find housing through expensive and sometimes illegal second- or third-hand contracts. Sub-letting outside of the quite strict rules have long been illegal, but recently also sub-renting became illegal, thereby criminalizing vulnerable groups in a way Sweden is proud not to do when it comes to other cases like drug abuse or prostitution (CRUSH, 2021).

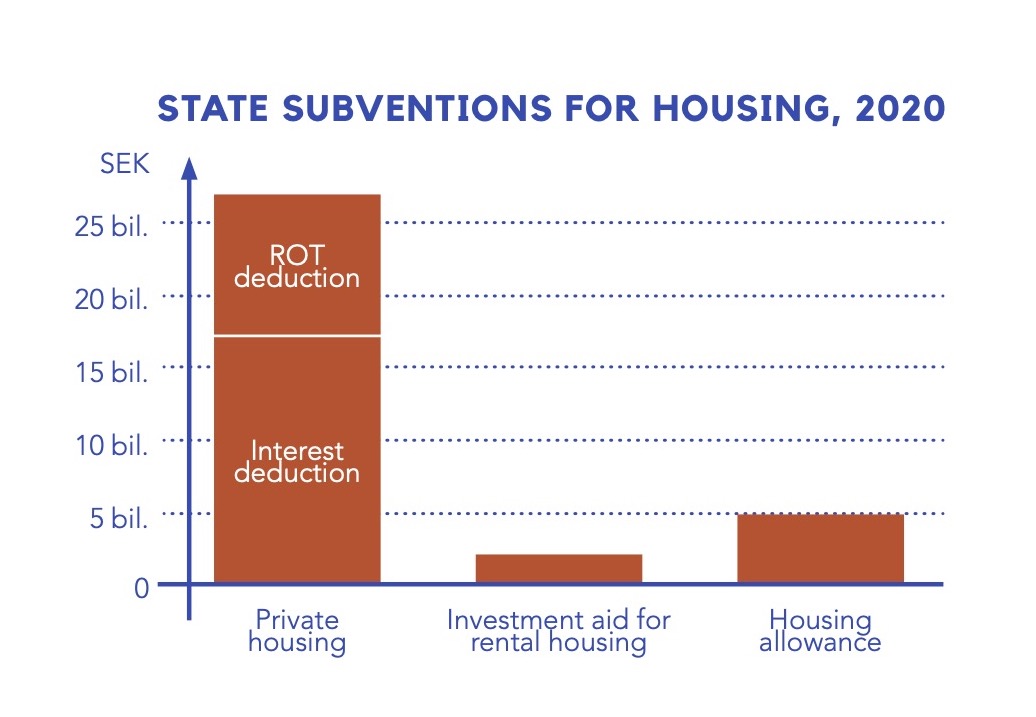

While the housing shortage is most pressing among those who cannot afford to buy a home, the state subventions are geared towards those who can. Looking at the costs of different subventions for housing it is clear to see that the most part of the state housing expenses goes to those who already own their home and not to making sure vulnerable groups get better access to housing.

The deductions for private housing that cost the state 28 billion in 2020 went primarily to affluent households. There is a clear correlation between income and interest and renovation deductions: the higher the income, the greater the deductions. In 2019 over a third of the state cost of ROT-deductions went to households with an annual income of over half a million SEK. The recent change in property taxation also favoured those with the most valuable assets (hurvibor.se, 2021). Although the new investment aid for rental production is a step towards a more balanced distribution of housing subventions it is clear to see that the state heavily favours owned housing over rentals.