Page II – Discourse

Discourse – an introduction

This project started from an urge to investigate the architectures and infrastructures of the mediation of transnational migration. As the discourse of migration – and the processes that facilitate and condition it – is an entirely new topic for me to tackle on an academic level, and as it is so vast and touching so many aspects of modern society, I had to start at the very beginning. I felt the need to approach the discourse from a systemic level, understanding and analysing the processes of migration control, migrant territories and boundaries and how it all weaves together into a complex and intricate network. I wanted to avoid fulfilling the old tropes of how architects can and should relate to migration and borders in their professional life; designs for the refugee relief system, emergency shelters or flashy border stations. We need to expand on both our knowledge and understanding as well as reiterate our toolbox, in order to eventually expand both our realm of influence and potential for initiating change.

I wanted to learn what role architects and the built environment that we help shape can choose to assume in these complex systems, and to visualise the ways in which we may unconsciously (or otherwise) already be affecting displaced populations’ experiences of flight and boundaries to and within Europe.

While first attempting to map and build an understanding of the systems and processes that shape the reality of migration, the project eventually condensed into a comparative study of Europe’s external border conditions, viewed through the lens of irregular migration. As irregular migration is increasingly viewed as an external threat to the safety and identity of the nation state, so nations see the need to increasingly secure their external borders. As such measures does not remove the initial reasons to migrate, it does nothing to eliminate the migrant journeys themselves. All it does is redirect and divert the routes away from ones own territory, in affect displacing the responsibility of caring for migrants to other territories.

This perilous dance of border securitization, shifting migration flows, and the trail of border infrastructure it leaves in its wake, all happens at the expense of both increasing violence and risk for life of the migrant. Sovereign state governments and the EU alike, continues to promote and finance an increasing militarization of their border conditions – all done in the name of free movement and liberty within.

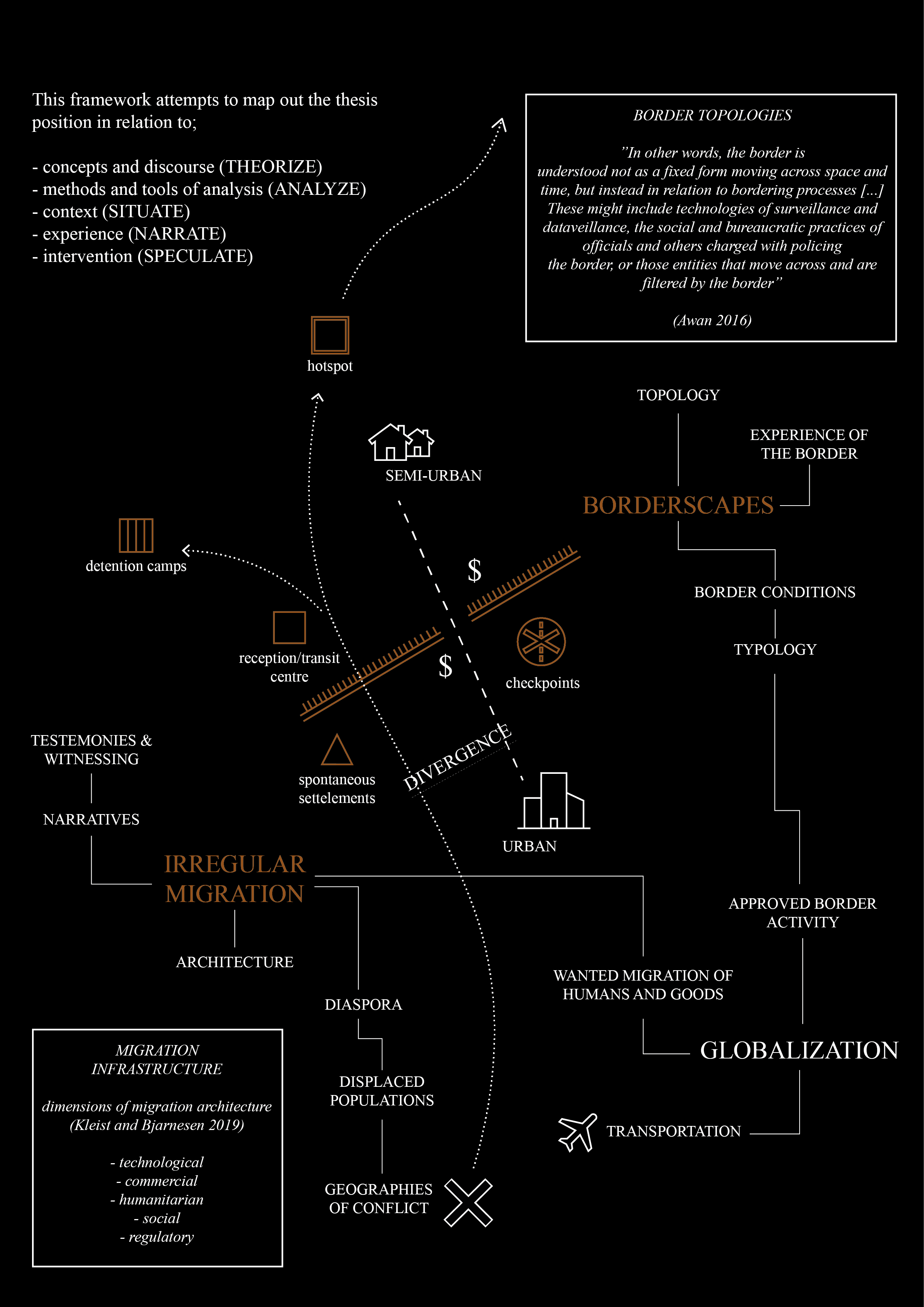

Theoretical framework

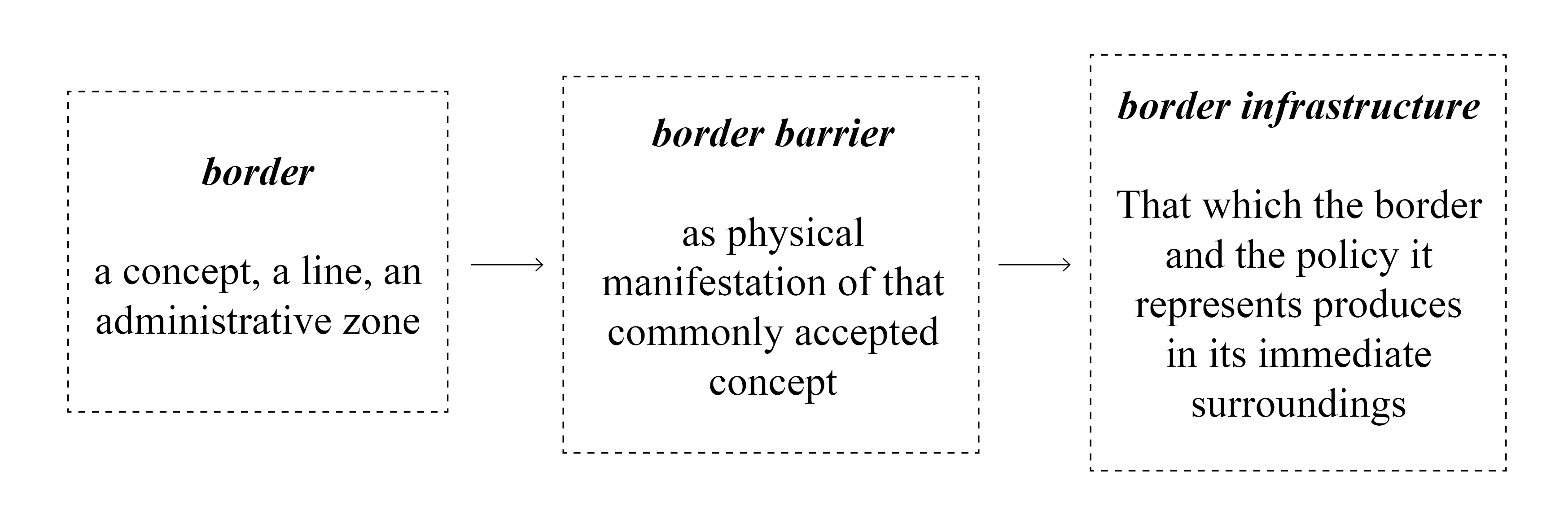

Outline the discourse of bordering processes and typologies, architecture for migration control and cross-border activities such as global trade and tourism. In the discourse on the architectures on migration I have employed an analytical framework of migration infrastructure (looking into the spatial, human and technological dimensions of migration processes). To understand the functions and operations of the border I have employed a framework of border topologies (understanding the border as a network of agencies, technologies and built structures that all have interwoven connections and relations).

Border typology & Separation

The border acts as an agent for multiple contradictory narratives and experiences of territory. We can consider the spatial manifestation of the border as; barrier – a physical obstruction of movement and a potentially oppressive instrument of power, as well as; facilitator – of movement and activity across its territory for the select few. For those who are allowed to move freely across the borders within Europe, the border and its instances of control and surveillance may be experienced as a mere security measure – or even a facilitator of opportunity, due to its typical attraction of commercial and recreational cross border activities.

By comparing the architectures and infrastructure that help produce these two very different experiences of moving across and existing around borders, one can start to understand and speculate on the border’s inherently spatial nature and it’s importance as an agent in the discourse on migration and globalization. The understanding of the border as barrier versus facilitator can come to identify separations and intersections, overlaps and divergences inherent to the contradiction. These identified situations, where vastly different experiences of the border occur either in the same territory or as actively separated, has the possibility to become

test beds for new ways in which to imagine and engage with borders and the built environment in borderlands. These are the situations where one can eventually hope to speculate on possible interventions for a more inclusive and sustainable future.

Migration flows & Border securitization

The investigation takes as its starting point the constantly shifting context of transnational migration within challenging and improvisational border conditions. Borders appear as a product of the construction of the nation state – approached by many as the ultimate human political invention (Donnan and Wilson 2010), and as such, the border plays an important role in securing the sovereign state from various external threats. Irregular migration has, by some states and by some political ideologies more than others, been identified as one such threat against state identity and security.

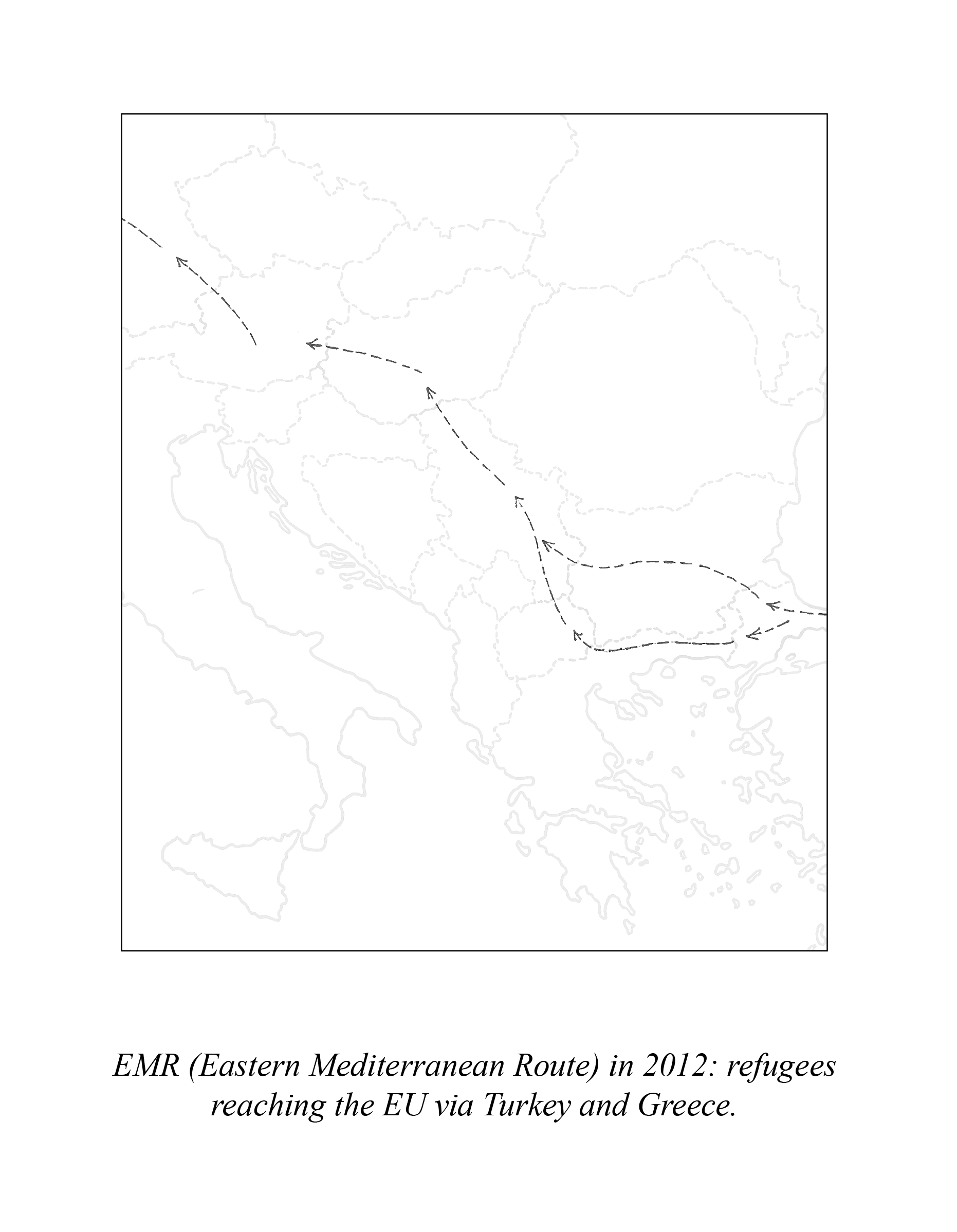

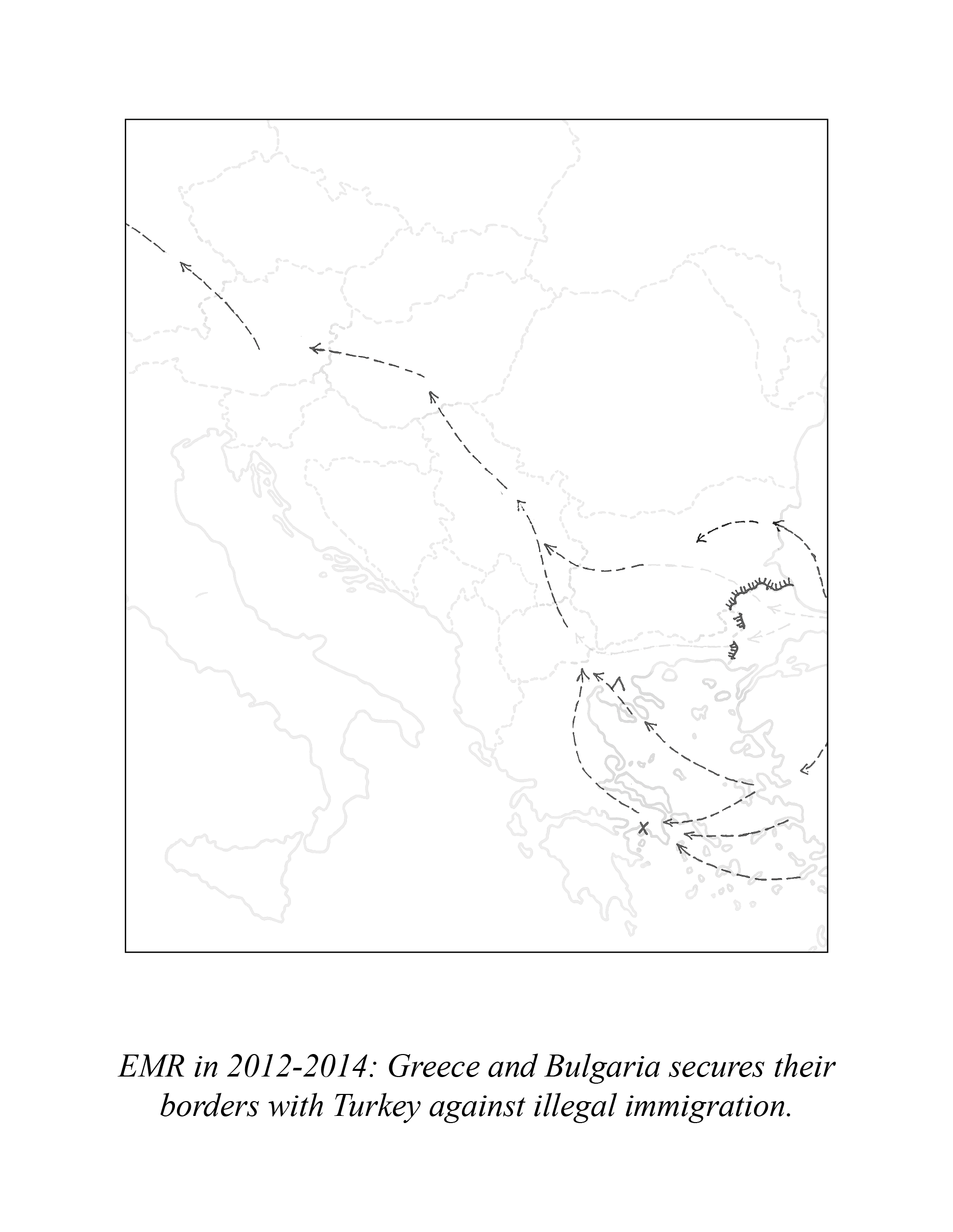

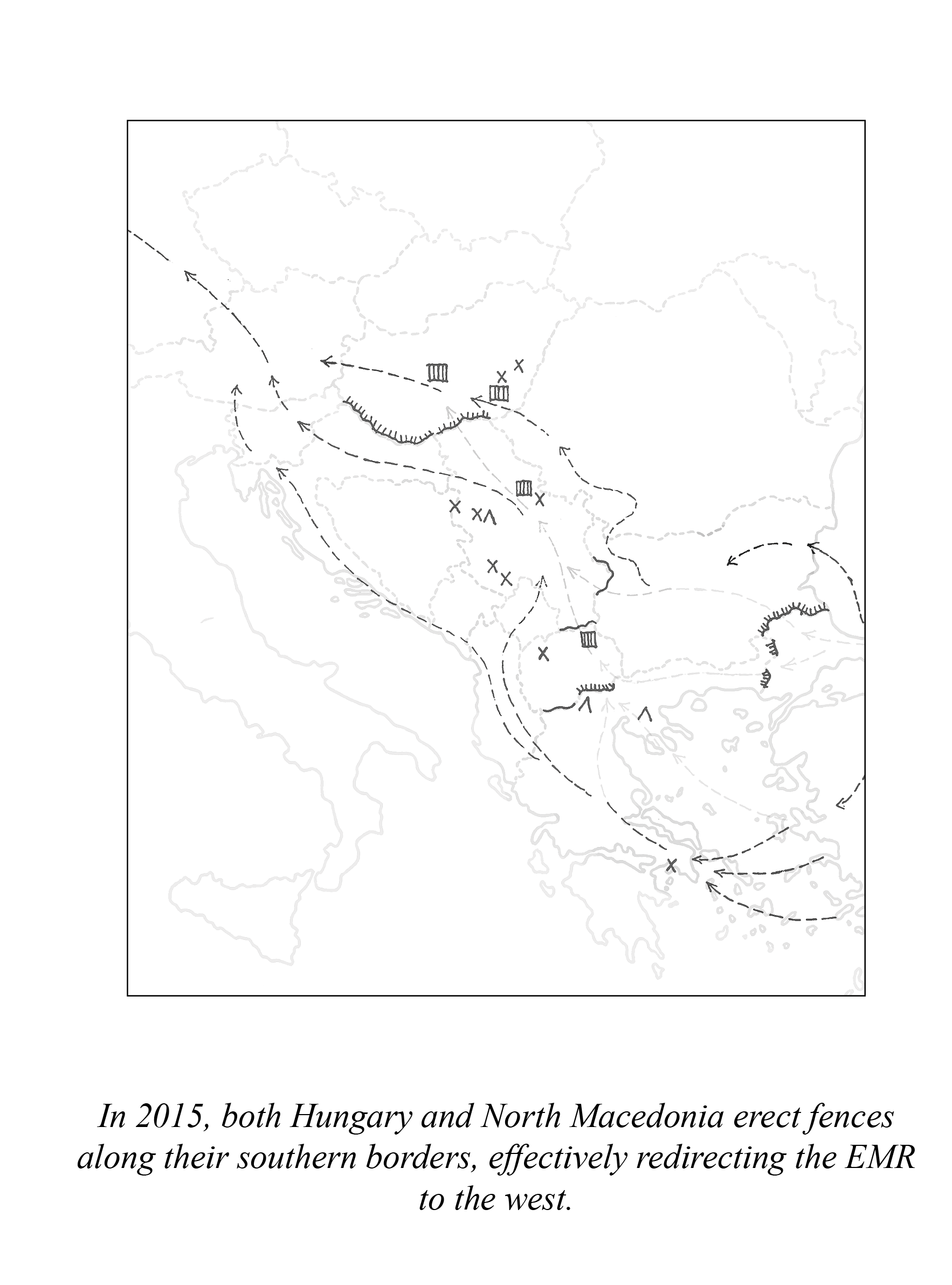

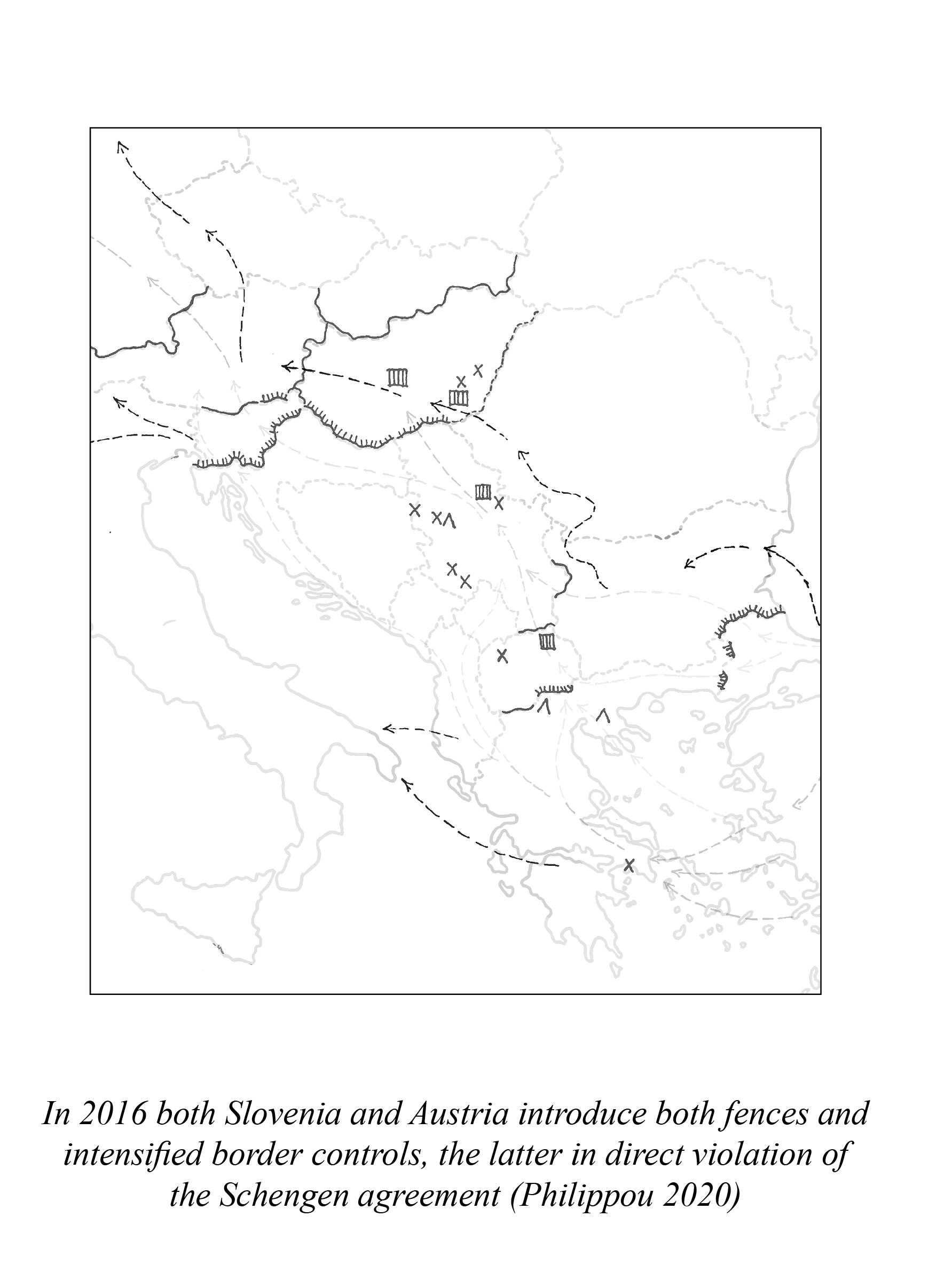

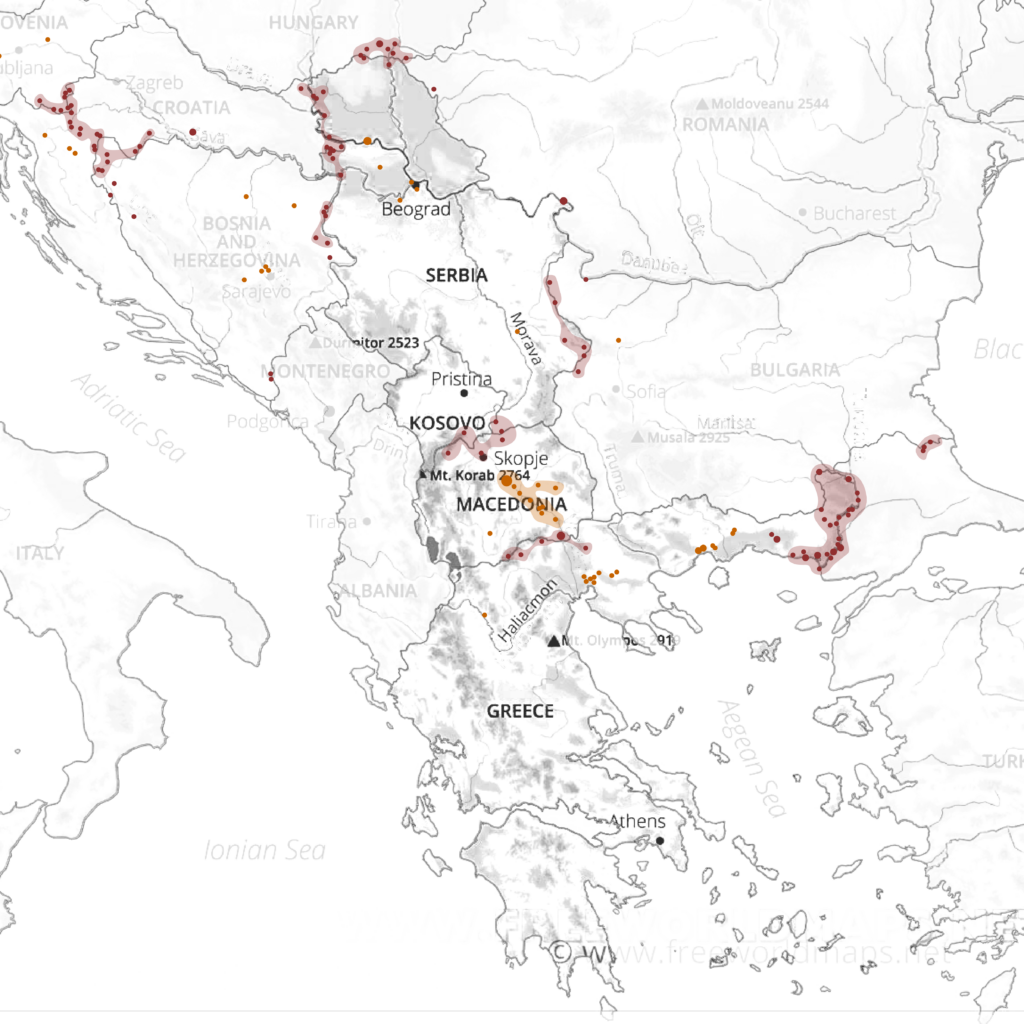

As migratory journeys to Europe stake out the simplest paths towards the desired destination country, various transit states along that route invests in different types of infrastructure and architecture in order to control, regulate and accommodate the influx of people across their borders. Many such measures, such as the construction of border walls and fences, have been known to be encouraged and sanctioned by the EU (Donnan and Wilson 2010) – in affect an externalization of EU border control. As borders solidify and become increasingly difficult to cross, or if the incidents of border violence, imprisonment or deportation rise, migratory routes re-direct, leading to new entry points and the corresponding increase in border infrastructural response in that region. As a result, we can see the constantly shifting migration routes and humanitarian corridors leaving behind them a trail of built border barriers and other built structures, evidence of the nation state’s desperate attempt to displace the responsibility of caring for these in search of safe ground (Philippou 2020).

One example of such spatial expressions of borders and migration mediation, and its development over time, is that of the Eastern Mediterranean Route (EMR) during the European refugee crisis in 2011-2016, as visualised to the right.

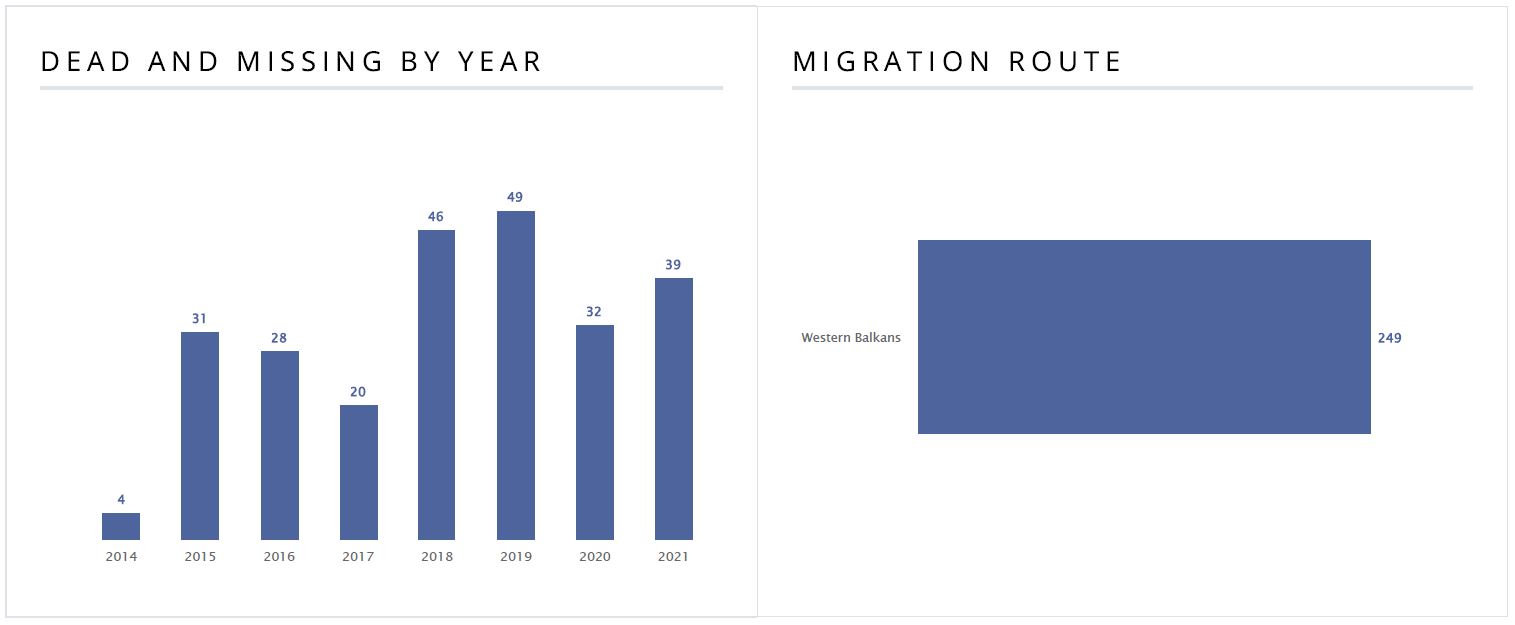

Deaths at the border

As there are very limited legal ways for migrants and refugees to enter and subsequently apply for asylum in the European Union, people are forced to resort to more and more perilous journeys to safe ground. Increasing surveillance, patrolling and the erection of physical border barriers play a crucial role in forcing those crossing land borders to go to even greater lengths to cross the border unnoticed.

“Most migration in Europe is intraregional, meaning that the majority of migrants in Europe come from another European country. It is enabled by the freedom of movement and common visa system of the 26 countries in the Schengen Zone. Nonetheless, some people without legal status in the Schengen Zone and other countries in Europe migrate irregularly within the continent, which can pose risks to their lives.”

(Missing Migrants Project, IOM)

Europe’s borderlands are becoming increasingly dangerous for irregular migrants as the rhetoric around immigration are (again) becoming harsher.

This becomes clear when we look at the amount of migrants that go missing on their journey. According to the IOM (International Organisation of Migration) and statistics on reported migrant deaths collected in the IOM-initiated project Missing Migrants (https://missingmigrants.iom.int/), despite lower number of migrants along the EMR (Eastern Mediterranean Route, aka. Westen Balkan route) death tolls remain high. In fact, the number of dead or reported missing migrants have been higher in 2018-2021 than during the refugee crisis of 2015-2016.

”Since 2014, more than 4,000 fatalities have been recorded annually on migratory routes worldwide. The number of deaths recorded, however, represent only a minimum estimate because the majority of migrant deaths around the world go unrecorded. Since 1996, more than 75,000 migrant deaths have been recorded globally. These data not only highlight the issue of migrant fatalities and the consequences for families left behind, but can also be used to assess the risks of irregular migration and to design policies and programmes to make migration safer.”

(Missing Migrants Project, IOM)